In 2022, Russia launched a surprise assault on northern Ukraine, using Belarusian territory as a staging ground. This rapid advance toward Kyiv exposed a critical weakness: decades of Soviet-era drainage projects had eliminated much of the natural swamp terrain that once acted as a defensive barrier. What was once a maze of waterlogged wilderness had been transformed into dry, passable corridors for enemy vehicles.

Ukraine cannot allow history to repeat itself.

The strategic value of wetlands as defensive barriers is well-established. NATO’s newly acquired Finnish border with Russia runs largely through swampy terrain that has historically reduced the need for large troop deployments, forcing potential threats into predictable corridors.

While traditional military defenses remain necessary, an unconventional yet proven solution is gaining attention: swamp restoration. Reviving the peat bogs and wetlands of regions like Polissia could once again make large swaths of land impassable to tanks and armored vehicles. This strategy not only enhances national defense but also improves water regulation and creates economic opportunities for local communities.

Chernobyl and the vanishing swamp barrier

During their 2022 invasion, Russian troops advanced through the Chernobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve. The wetlands in this area had been drained either before or shortly after the 1986 nuclear disaster. As a result, Russian military vehicles moved easily across the dry terrain, kicking up clouds of radioactive peat dust. Radiation levels near the Chernobyl power plant temporarily spiked by a factor of 20.

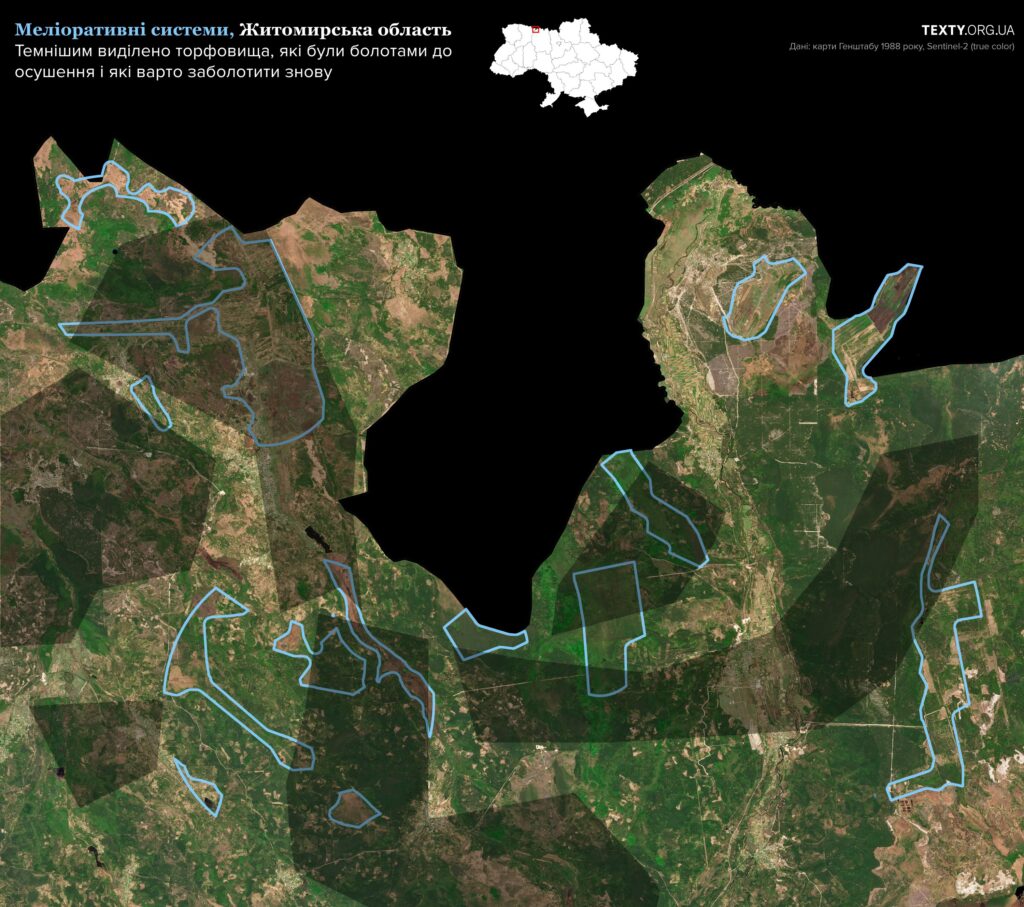

The Polissia region stretches across northern Ukraine, overlapping Zhytomyr, Rivne, Chernihiv, and Volyn oblasts. Historically, it was home to one of Europe’s most extensive systems of peat bogs and wetlands. These swampy landscapes were so dense and waterlogged that they were once considered impassable.

But that changed during the Soviet era.

From the 1950s through the 1980s, the USSR launched widespread melioration projects that drained over 1.2 million hectares of Ukraine’s estimated 2.2 million hectares of peatlands. Drainage systems and canals were constructed to convert wetlands into farmland or to extract peat and amber. The ecological cost was enormous, but it also removed one of Ukraine’s most effective natural defense systems.

“If the swamps had still been there, the tanks wouldn’t have gotten through,” said a resident of Makariv, northwest of Kyiv.

Why swamps beat tanks: Nature’s best border defense

Swamps may appear benign, but they can be a nightmare for modern armies. Wheeled and tracked vehicles, including tanks and armored personnel carriers, sink or stall in saturated peat soil. Roads become unreliable or nonexistent, and logistics chains break down.

Only a limited range of amphibious or hovercraft vehicles can navigate these terrains—equipment that most land armies, including Russia’s, do not typically deploy far from water.

In fact, during a 2024 NATO training exercise in Lithuania, a tragic accident highlighted this very issue. Four American soldiers drowned when their armored vehicle sank in a peat bog they mistakenly thought was firm ground.

“Swamps can act as a passive but highly effective barrier—requiring no fuel, no guard, and no concrete,” said German ecologist Dr. Thomas Ziegler, co-author of a study on wetland defense strategies in Eastern Europe.

Belarus is paving the way—literally

The strategic value of Ukraine’s peatlands is also clear to Russia and Belarus. Since 2015, Belarus has constructed over 100 kilometers of roads through the Olmany-Perebrody peat bog system, which straddles the Belarus-Ukraine border. These roads now connect to existing Ukrainian infrastructure.

If Ukraine’s side still had intact swamps, the Belarusian effort would have been strategically futile. Instead, these roadways could become invasion routes, just as they were in 2022.

Many of these routes lead toward Zhytomyr and Novograd-Volynskyi, placing key logistical and population centers at risk. And while peacetime roads encourage trade and travel, in times of conflict, they can become liabilities.

How Ukraine can bring back its swamp defense

In rebuilding Ukraine’s swamp defenses, simple and low-cost solutions can be surprisingly effective. One model comes straight from nature: beavers. Their dams, built with wood and mud, are low-tech yet capable of restoring water levels in peatlands. Humans can replicate these structures using locally available materials. While not permanent, such barriers work well if maintained—and once water levels rise, real beavers often return, further reinforcing the wetlands.

Rewetting, or restoring water levels in degraded peatlands, is not a new concept. But applying it for military and environmental goals is gaining traction.

The process involves:

- Blocking drainage canals using clay, peat, or natural materials.

- Constructing dams or barriers, sometimes mimicking beaver dams.

- Redirecting water from nearby rivers or rainfall catchment areas.

- Monitoring hydrology to ensure long-term saturation.

A pilot project in the Roztochchia Nature Reserve in Lviv Oblast, launched in 2021, used water pipes, overflow dams, and re-engineered canals to begin the rewetting process. The project proved that old drainage systems can be repurposed to retain water rather than remove it.

“We’re reversing decades of damage,” said Oleksandr Sokyrko, an ecologist involved in the project. “The moment water rises, nature begins to rebuild.”

Swamps begin to recover naturally once water levels rise, supporting biodiversity and reducing fire risks.

The price of protection: Swamps vs. concrete bunkers

Rewetting peatlands in Ukraine costs between €300 and €1,500 per hectare, with the variation depending on factors such as the size and location of the site, existing infrastructure, technical documentation, and accessibility. Full rewetting typically takes 2 to 4 years, as water levels must rise gradually and consistently. One year is rarely sufficient.

Even with these considerations, rewetting remains significantly more cost-effective than constructing and maintaining concrete bunkers or constantly repairing waterlogged trenches. Once restored, swamp-covered zones also require fewer personnel to defend.

Instead of building more expensive fortifications, Ukraine has the opportunity to create a natural, impassable barrier while replenishing critical water reserves. According to German ecologists, this strategy strengthens European security and helps restore hydrological systems, including vital flows to the Dnipro River. Concrete bunkers will still play a role, but fewer will be needed where nature itself serves as a front line.

Ukraine also holds a unique advantage: much of the northern border region is state- or communally-owned land, making it easier to launch swamp defense projects without complicated private property disputes, as often seen in the EU.

Legal and military framework

Since the full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s government has enacted emergency laws allowing the military to repurpose land within two kilometers of the border with Russia or Belarus for defense infrastructure. This includes converting farmland or forest into swamp restoration zones.

That legal authority, combined with public ownership and local expertise, makes wetland restoration a fast-track defense policy ready for implementation.

Rewetting vs. restoration

Restoring peatland ecosystems requires more than just raising the water level; it demands expertise Ukraine is still developing. However, rewetting—simply raising water levels—is a more straightforward process that can yield fast defensive and ecological benefits. Higher water levels can create new wetland zones or allow the cultivation of water-tolerant plants.

This approach is both more affordable and offers potential economic benefits, but ongoing water-level monitoring is essential to ensure that terrain remains impassable to enemy vehicles.

More than defense: Practical gains

There is also agricultural potential. Ukraine is among the world’s top 10 exporters of wild cranberries, a plant that only grows in peat bogs. With proper management, regenerated swamps could support sustainable cranberry harvesting and even export-certified organic berries at premium prices.

“We can turn our bogs into shields and farms at the same time,” said a representative from Ukraine’s Ministry of Agrarian Policy.

Water for the enemy?

Most of Ukraine’s large-scale land drainage infrastructure was built during the peak of Soviet melioration in the 1960s–1980s. In some cases, these systems still redirect water from Ukrainian peatlands into Belarus. In a time when water is a strategic resource, Ukraine is effectively supplying its adversary for free.

Barriers and challenges

Despite its promise, swamp restoration faces several hurdles:

- Amber mining continues in the north, involving drainage and excavation.

- Peat extraction licenses are still being issued in some oblasts.

- Technical expertise is limited, with few Ukrainian specialists in peatland hydrology.

- Ongoing conflict complicates access to sensitive or dangerous areas.

However, international support is growing. The German Michael Succow Foundation, UNEP, and WWF-Poland have offered to provide technical guidance, free consultations, and in some cases funding.

Final word: Ukraine’s fortress of water and peat

Ukraine’s Soviet-era decision to drain Polissia’s wetlands may have served short-term agricultural goals, but it weakened the country’s strategic defenses. Now, with ongoing war and increasing water stress, the country has a chance to turn that mistake into strength.

By restoring the swamps, Ukraine can:

- Build a natural, low-cost defensive line.

- Improve regional water retention.

- Reduce harmful peat fires.

- Support rural economies.

As wetland defense experts have noted, restored peatlands can act as passive fortresses—impassable to tanks, low-cost to maintain, and capable of slowing and redirecting enemy movements.

Ukraine’s future defense may not lie only in steel and concrete—but also in moss, peat, and rising water.

Read also

-

On Trump’s request, Belarus releases 14 political prisoners charged for opposing government and its support for Russia’s war

-

Frontline report: Poland orders 500 HIMARS and 1,000+ tanks as Russia’s shadow creeps through Belarus

-

Inside Belarus’ Cyber Partisans who derailed Putin’s “Kyiv in three days” war plan