- Ukrainian drones struck two Russian Antonov An-26 airlifters at Kacha airfield in occupied Crimea

- An-26s transport cruise missiles and attack drones from factories to front-line bases—disrupting Russia’s strike capability

- Satellite imagery confirms one An-26 completely destroyed, debris already cleared from the base

- Part of coordinated campaign targeting Russian air defenses, airfields, and logistics across Crimea

The Antonov An-26 is a twin-turboprop transport plane with a 26-ton maximum takeoff weight. The Russian air force has around 100 of them, and uses them to haul supplies, drop paratroopers, and even—in a rare secondary role—inaccurately lob unguided bombs.

But in the current wider war on Ukraine, the 5-crew An-26s are busy on a vital mission for Russia. They haul cruise missiles and long-range attack drones from their factories to the front-line bases that launch the drones … or the warplanes that then launch the cruise missiles.

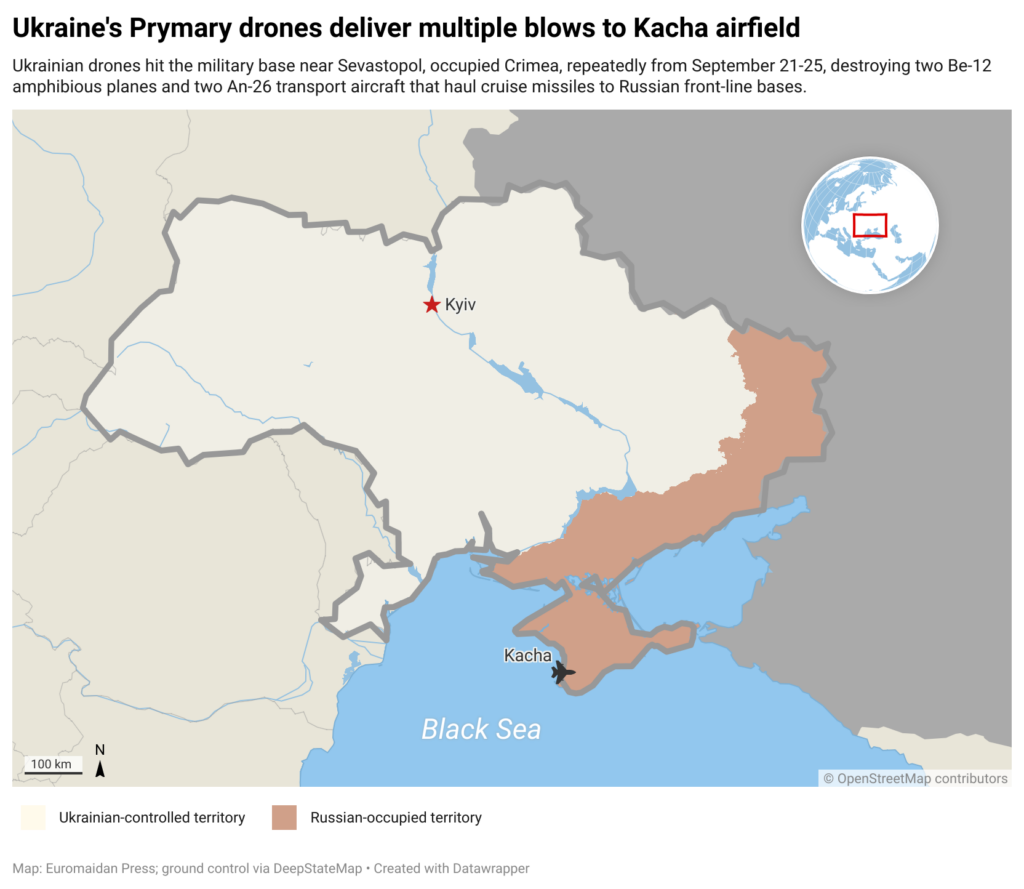

And that’s why it was such a big deal when, on 21 September, attack drones from Ukraine’s Prymary unit blew up two of the An-26s parked at Kacha airfield in Russian-occupied Crimea, 215 km from the southern front line.

Multiple strikes on Kacha

The attacks on Kacha didn’t end on 21 September. Ukrainian forces hit the airfield repeatedly over several days, systematically degrading this key logistics hub:

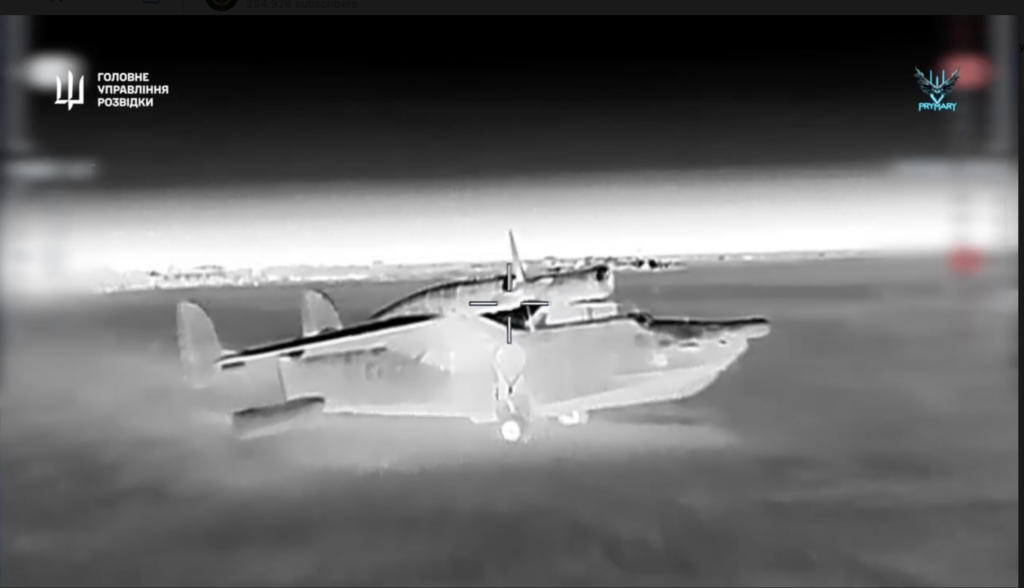

- 21 September: HUR’s Prymary unit destroys two Be-12 amphibious planes—first time these Soviet-era aircraft were destroyed in combat

- 22-23 September: Ukraine’s General Staff confirms another strike hitting two aircraft at the airfield

- 24 September: Powerful explosions reported around Kacha and Belbek airfields at 04:30

- 25 September: HUR strikes two An-26 transport aircraft and coastal radars; satellite images confirm one An-26 (RF-46878 “Blue 30”) completely destroyed.

Ukraine’s drones torch two Russian transport aircraft and two radars in occupied Crimea — and film the whole thing (video)

Prymary’s expanding strike campaign

Ukraine is trying to disrupt Russia’s own air raids—by attacking the people, equipment, and bases supporting those raids.

The destruction of the two An-26s is the latest in a drumbeat of successful strikes by Prymary using fixed-wing first-person-view drones ranging hundreds of kilometers, presumably connected to their distant operators via Starlink or some other satellite communications system.

Starlink works just fine over Crimea but doesn’t work over Russia proper, lending units such as Prymary the ability to employ highly maneuverable FPV strike drones rather than less accurate models that may rely on, say, some unjammable internal inertial navigation system.

In the span of just a few days, Prymary has struck six Russian Mil Mi-8 assault helicopters in Crimea as well as two Beriev Be-12 flying boat patrol planes. Whether the targeted Berievs were flyable is up for debate. There are some derelict ex-Soviet Be-12s sitting around various Crimean airfields.

But at least a few of the 1970s flying boats are still active, patrolling the approaches to the Russian Black Sea Fleet’s anchorages in Crimea and, presumably, southern Russia. Meanwhile, FPV drones have hit several Russian warships and auxiliary vessels in the waters around Crimea.

Coordinated campaign

The events are not unrelated. In a well-planned strike campaign, one attack enables others.

To facilitate the hits on airfields, Prymary first took out Russian air defenses in Crimea.

Those strikes have continued as the airfield raids have escalated. The same set of drone sorties that hit those two An-26s also took out an Mys M1 coastal radar.

It’ll take two more wrecked An-26s to seriously interfere with Russia’s ability to move missiles, drones, and other munitions around its network of bases surrounding free Ukraine.

Other Russian airlifter types also help haul munitions—in particular, the 209-ton, quad-jet Ilyushin Il-76s. And there are even more of those.

Targeting the supply chain

But Prymary’s strike campaign is just getting started. It’s clearly aimed “left of boom,” to borrow a US Army term.

It’s much easier, cheaper and safer—for Ukrainian troops and civilians—to destroy the infrastructure supporting Russian bombardment of Ukrainian cities than it is to intercept incoming missiles and drones right before they strike.

Prymary isn’t the only Ukrainian unit aiming left of boom, of course. Sometime recently, Ukrainian forces located a major launch site for Russia’s best Iskander ballistic missiles—and blew it up, reportedly with a swarm of 14 long-range attack drones. The launch site may have been in Molkino, in southern Russia 450 km from the front line; however, other observers have geo-located it as Shumakovo, in western Russia much closer to the front.

Ukraine and Russia now hunt each other’s missile crews in deadly “left of boom” race

The Russians have adopted the same strategy, however.

On 28 August, a Ukrainian navy Neptune cruise missile battery tried to strike targets in southern Russia’s Krasnodar Krai region. The strike failed as Russian S-300 air-defense missiles rose to intercept the incoming Neptunes—and then the Russians struck back.

A surveillance drone spotted a truck-mounted Neptune launcher, apparently the same launcher that targeted Krasnodar Krai. An Iskander ballistic missile streaked down, damaging if not destroying the Ukrainian launcher, geolocated at Liubytske, just near the front line in Zaporizhzhia Oblast.