Key points:

- The best deep-strike missiles can be hard to intercept in the air

- Missile launch crews are easier targets—on the ground

- Both Russia and Ukraine are hunting each other’s missileers

- The Americans have a name for this approach: striking “left of boom;” it mirrors US counterinsurgency tactics from Iraq, Afghanistan

Forty-three months into Russia’s war, Ukraine has finally developed serious deep-strike capabilities. Homegrown drones and cruise missiles can now reach hundreds of kilometers into Russia—capabilities Ukraine built because Western allies restrict how their donated weapons can be used against Russian territory.

Ukrainian missile and drone teams are scoring real hits—and becoming top targets as each side escalates its deep strikes on the other. When you struggle to shoot down a missile mid-flight, hunt down the troops who launch it, instead.

When missile defense fails, hunt the crews

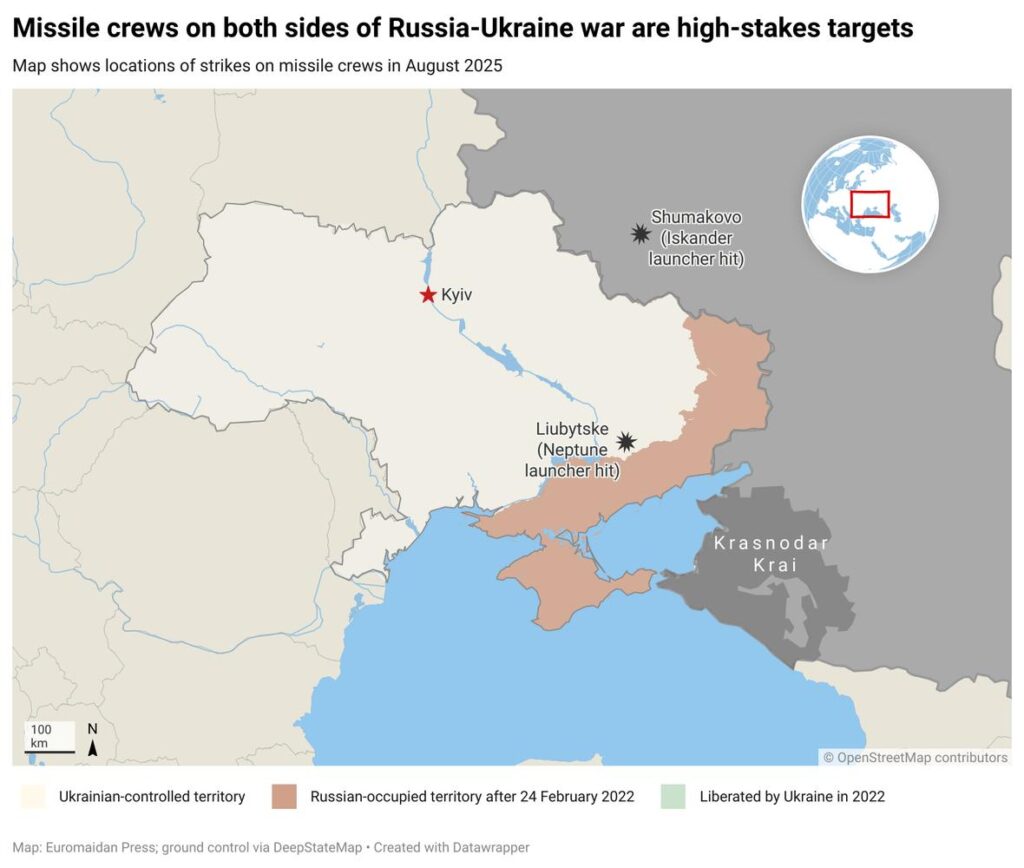

Sometime recently, Ukrainian forces located a major launch site for Russia’s best Iskander ballistic missiles—and blew it up, reportedly with a swarm of 14 long-range attack drones. The launch site may have been in Molkino; however, other observers have geolocated it as Shumakovo, 100 km from the border.

In any event, photos clearly depict the aftermath and hint at the scale of the damage. The Russians lost multiple vehicles associated with the 4-ton Iskander and a Pantsir air-defense vehicle.

It was a significant victory for Ukrainian drone operators.

Iskander’s advantages that make interception difficult:”

- Travels up to 500 km at seven times the speed of sound

- Only Ukraine’s best air defenses can intercept (Patriot, SAMP/T)

- Ukraine operates fewer than 10 such batteries combined

- Too few systems to protect every potential target

An Iskander can travel as far as 500 km at a peak velocity seven times the speed of sound. Only Ukraine’s best air defenses—its US-made Patriot batteries and European-made SAMP/Ts—can hit incoming Iskanders in the air.

But the Ukrainian air force operates fewer than 10 Patriot and SAMP/T batteries, combined. That’s too few to protect every possible target.

It’s imperative to hit the Iskander launch crews “left of boom,” to borrow a US Army term. That is, to hit them and their missiles and equipment on the ground.

The Americans refined their left-of-boom philosophy during the grinding counterinsurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan, where front-line troops struggled to spot and defeat the many thousands of improvised bombs that insurgents had planted along the roads and footpaths of both countries every month.

Instead of trying to locate every emplaced bomb, American intelligence teams and drone operators hunted the insurgents who were building and emplacing the bombs. More than a decade later, the Ukrainians must do the same to blunt the damage from Russia’s fastest and hardest-to-intercept missiles.

Russian Iskander vs Ukrainian Neptune: crew vs crew

The problem, of course, is that the Russians are applying the same philosophy. And the Iskander itself is part of their own left-of-boom operations.

The Neptune incident in August shows how quickly the hunter can become the hunted.

On Aug. 28, a Ukrainian navy Neptune cruise missile battery tried to strike targets in southern Russia’s Krasnodar Krai region. The strike failed as Russian S-300 air-defense missiles rose to intercept the incoming Neptunes—and then the Russians struck back.

A surveillance drone spotted a truck-mounted Neptune launcher, apparently the same launcher that targeted Krasnodar Krai. An Iskander ballistic missile streaked down, damaging if not destroying the Ukrainian launcher, geolocated at Liubytske, just near the frontline in Zaporizhzhia Oblast.

It was the most expedient way of defeating a Neptune.

“The Kremlin simply does not have enough air defense systems to protect thousands of potential military and energy targets spread across 11 time zones,” explained Ukrainian-American war correspondent David Kirichenko wrote.

In that context, the successful aerial interception of the Neptunes streaking toward Krasnodar Krai may have been an outlier. And it makes sense for the Russians to target the Neptunes’ launch crews and equipment on the ground.

Ukraine’s missile crews know they’re being hunted

Ukrainian missileers, as well as launch teams for long-range drones, must know they’re being hunted. Every time they roll out for a launch, Russian drones will be looking for them—and Russian ballistic missiles will be ready to take aim.

It’s not for no reason that Ukrainian missile crews are downsizing their operations: launching fewer missiles at a time to speed up the process and minimize their exposure to overhead surveillance.

Iryna Terekh, an executive from Fire Point—the company that builds Ukraine best new Flamingo cruise missile—recently admitted the firm wasn’t yet “satisfied with the scale of launches,” to quote Militarnyii. But Terekh conceded that the launch crews operate under extremely dangerous conditions.

If anything can comfort the endangered Ukrainian missile teams, it’s that Russian missile teams are in equal danger.

Risks facing Ukrainian missile crews:

- Russian surveillance drones constantly searching for launch sites

- Ballistic missile strikes within minutes of detection

- Forced to minimize exposure time and launch fewer missiles per mission

- Operating under “extremely dangerous conditions,” per Fire Point executive