Ukraine’s strongest ally just elected a president who wants to cut refugee benefits, block EU membership, and exploit historical grievances. How did Poland—once Ukraine’s loudest champion—turn against its neighbor?

To the south, Romania nearly elected the far-right and pro-Russian George Simion. To the west, Slovakia’s Robert Fico and Hungary’s Viktor Orban have long parroted Kremlin talking points and tried to block aid to the embattled country. Now Poland, long one of Kyiv’s most consistent, vocal, and strongest allies, has begun to sour on its neighbor as well.

Since Russia initiated a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Kyiv has received tremendous diplomatic support, especially from its neighbors in the region. However, after more than three years of war, cracks in this support are beginning to show.

The culmination of this trend was in June 2025 with the election of Karol Nawrocki. An arch-conservative and nationalist, Nawrocki has promised to limit benefits to Ukrainian refugees, block Kyiv’s accession to NATO and the EU, and has stoked historical trauma between the states.

A nail biting contest

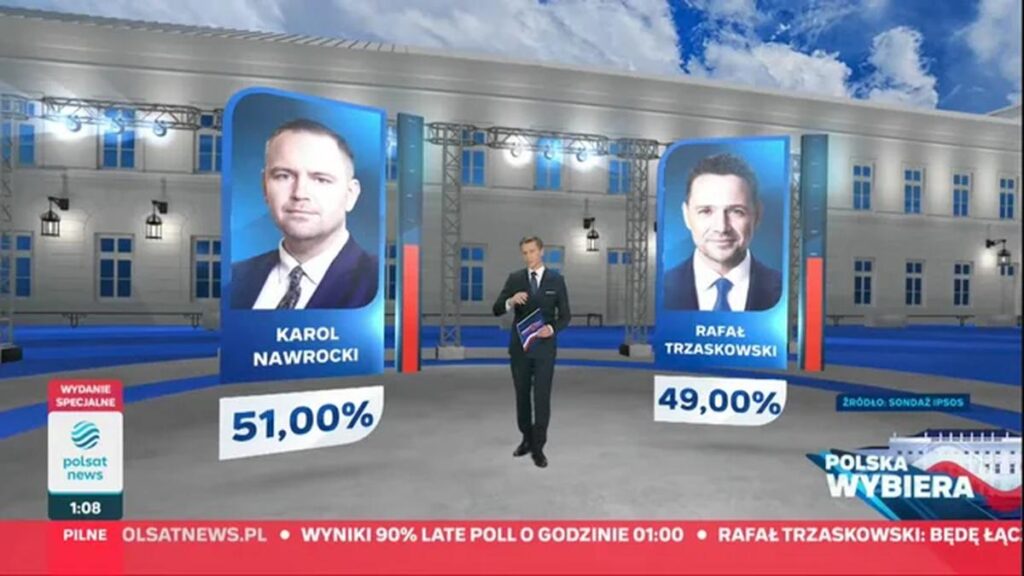

For weeks, journalists, analysts, and politicians have been watching Poland’s presidential election cycle. What was initially predicted to be a walk in the park for the liberal centrist candidate, Rafał Trzaskowski, has become a neck-in-neck race with his conservative challenger, Karol Nawrocki.

A few months ago, many Poles would have struggled to even identify Karol Nawrocki in a photo lineup. The former head of the Institute of National Memory (IPN), many were surprised when Jarosław Kaczyński, leader of the conservative party Law and Justice (PiS), selected him to run for president.

After spending weeks catching up to Trzaskowski, Nawrocki barely snatched victory on 1 June.

Why was Nawrocki successful?

Nawrocki’s previous obscurity made his victory surprising. His main challenger appeared to be a tailor-made presidential candidate, while Nawrocki was dogged by scandals—allegations of football hooliganism, exploiting an elderly man for cheap rent, potentially soliciting prostitutes.

Instead, the main advantage for Nawrocki was that he was in the right place at the right time.

The ruling government coalition, headed by Donald Tusk, is an unwieldy creature comprising the progressive left, centrist liberals, and conservatives. Since coming into power in 2023, it has become incredibly unpopular.

United more in their antipathy towards PiS, the parties have proved adept at angering most segments of Polish society.

Tusk’s coalition had promised everything and delivered few of its core pledges. The abortion liberalization bill failed by just three votes because members of Tusk’s own coalition voted it down. Meanwhile, there has been no movement on legalizing same-sex marriage.

Conservative voters were incensed at the government undoing many of PiS’s former policies, while liberal and progressive urban supporters felt betrayed by broken promises.

Another factor playing in Nawrocki’s favor were efforts by the United States’ current Trump administration to back him.

In early May, Nawrocki attended the White House National Prayer Day and met with Donald Trump. Later that month, Homeland Security Director Kristi Noem urged Poles to vote for the conservative Nawrocki during a speech at the CPAC.

Tired of the new neighbors

The question is, why? Since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war, Poland has been one of Ukraine’s staunchest allies. It has taken in millions of Ukrainian refugees since February 2022; it has provided billions of złoty in aid; and has vociferously backed Kyiv on the global stage.

So then, how could that same country elect a candidate who threatens Ukraine’s EU membership and vocally calls for policies that would be harmful to Ukrainian refugees?

The transformation has been dramatic. Over one million Ukrainians now comprise nearly 7% of Poland’s population.

Polish support for Ukrainian refugees has plummeted from 94% in 2022 to just 53% today.

War fatigue has set in after three years of conflict with no end in sight

- More Poles now believe that Ukraine should give up territory to Russia to halt the war.

- The majority want military-aged Ukrainian men to return home.

- There is a growing sense that Ukrainian refugees take advantage of state benefits.

Economic competition narratives have taken hold despite evidence to the contrary. Ukrainian refugees have founded around 60,000 enterprises and boosted Poland’s GDP by 2.7% in 2024.

Many Poles are now receptive to restricting Ukrainian refugee benefits. Both major candidates proposed cutting the 800+ złoty monthly child benefit—roughly $170—that helps Ukrainian families, with Nawrocki promising outright cuts and Trzaskowski proposing to limit it only to working Ukrainian refugees.

This targets largely women with children, and the administrative costs of determining employment status would likely exceed any savings from the cuts.

A harsh new reality

So, what does Karol Nawrocki’s election mean for Kyiv? The consequences are mixed. While Poland’s crucial wartime support remains secure, longer-term strategic goals face new obstacles.

1. No threat to military support

Ukraine can breathe easy on one front: Poland’s military backing will continue. Nawrocki has declared support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and resistance to Russian aggression and explicitly supports giving military aid to help Ukraine fend off Russia’s invasion.

Poland will remain Ukraine’s vital logistics hub for Western arms deliveries and a vocal diplomatic advocate for Ukraine’s fight against Russia. The fundamental strategic partnership against Russian aggression stays intact—Nawrocki may be skeptical of Ukrainian integration, but he’s firmly anti-Russian.

2. Immediate impact on refugees

Unfortunately, this support will not extend past helping Ukraine fight Russia. As it relates to Poland’s treatment of Ukrainian refugees, Nawrocki has taken a hardline position and has vocally targeted the vulnerable group fleeing Russia’s vicious war.

In April, the then candidate declared that he would push for and sign a law that prohibited immigrants be treated better than Poles, “in their own country.” Ukrainians comprise the largest immigrant group, making the intent clear.

If Nawrocki were alone in pushing for these restrictive policies, life would be complicated for Ukrainian refugees, but still secure. The president has very few domestic affairs powers outside of the veto.

What is cause for concern is that many of Poland’s political class have also adopted anti-Ukraine stances. The current ruling coalition has voiced support for cutting child benefits for certain categories of refugees.

Poland is stepping up for Ukrainian refugees, but it cannot take everyone in

3. The long run

The second danger lies in Ukraine’s post-war future. Nawrocki has explicitly conditioned EU and NATO membership on resolving “civilizational issues”—primarily allowing Polish exhumations of Volyn massacre victims.

He declared that “a country that cannot answer for a very brutal crime against 120,000 of its neighbors cannot be part of international alliances.”

Despite Ukraine having acquiesced to exhumations earlier in 2025, Nawrocki has previewed how he will use the issue. In early June, Nawrocki publicly chastised Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy over the need to “[solve] overdue historical issues.” Days later, Poland passed a law establishing a day of remembrance for victims of “genocide.”

From open arms to political war: how Poland’s far-right turn Ukraine into a wedge issue

This triggered a diplomatic spat, with Ukraine taking umbrage over the word “genocide.”

This controversy represents a major point of contention between the two countries. Were the massacres of Poles in Volyn in 1943 a genocide, or a tragedy of war? Many Poles, not only conservatives, view the killings as a form of genocide. Ukraine believes that the matter should be viewed with more nuance, especially in the context of Polish animosity towards Ukrainians in the lead up to WW2.

Many conservative politicians in Poland would prefer to keep the Volyn massacres in the public eye. Much like with demands for war reparations from Germany, there is little reason for them to actually sit with the opposing side and come up with a sensible solution. Rather, it is advantageous to use these historical points of contention for political support.

Unfortunately, the current governing coalition, despite being opponents of Nawrocki, has signaled that they will also use this historical point of contention to gin up support.

Nawrocki has also identified agriculture as a pressure point, promising to prevent “unfair competition with Ukraine for Polish agriculture.”

This matters not because of agriculture’s economic weight—it comprises only around 3% of Poland’s GDP—but because of its political significance. Farmers represent a key constituency for conservative parties, and Ukrainian grain has triggered Polish farmer protests and border blockades.

4. The extremist threat

Like in the United States, Poland, despite being a parliamentarian and multiparty system, is largely divided into two blocs, conservative and centrist liberal. These two groups have been in power for decades.

Similar to their US peers, many young people in Poland reject this duopoly. Furious at the rising cost of living and economic instability, many youth voters sprinted to the far ends of the political system.

While some have thrown their weight behind the leftwing party Razem, far more have thrown in their lot with the far-right Sławomir Mentzen and his party Konfederacja. Mentzen has used the Ukraine war to his political advantage—organizing border blockades against Ukrainian trucks and targeting Ukrainian refugees with his rhetoric.

While the young firebrand’s support fell from a high of 18%, he still came in third during the first round with nearly 15% of the vote share, making inroads across demographics.

A gloomy forecast

If the governing coalition were to collapse, the far-right Konfederacja would have a huge advantage. It would be able to point to the inability of the two large parties to govern and play on the resulting disaffection. While Razem fully supports Ukraine’s fight and welcomes refugees, Konfederacja has shown that it has a larger support base.

Ukraine is currently faced with two major dilemmas.

- Putin and the Russian army continue to push westward, making small and costly gains, yet still stretching the limits of Ukraine’s manpower and logistics.

- Two of its closest allies, the US and Poland, have elected leaders who are either sympathetic to Russia, or view Ukraine as a tool to advance their nationalist agenda.

When the war finally ends, Ukraine will need all of the assistance it can get to both recover and quickly accede into the EU (NATO looks like it is out of reach). It is a shame that its future is clouded by the self-serving nationalism of its friends.