At 5:45 a.m. on 20 July 2024, a container of DHL parcels burst into flames right after security scanning at Leipzig Airport, Europe’s busiest cargo hub. The shipment was minutes away from being loaded onto a cargo plane. Inside the parcels were sex toys and cosmetics masking explosives.

Had they detonated midair, the blast could have torn the aircraft apart, killing its crew and people on the ground.

Less than 24 hours later, at 9:00 a.m. on 21 July, a second package ignited inside a truck trailer at a DPD depot in Jabłonowo, a village near Warsaw. The blaze spread through stacked pallets so quickly that it took four crews of 20 firefighters two hours to extinguish it.

On 22 July, a third device detonated inside a DHL transport warehouse in Birmingham, England, narrowly avoiding a larger disaster. And in Warsaw, Polish security services intercepted a fourth parcel before it could ignite. This one was disguised as a neck massage pillow, its padding concealing a timer, an ignition device, and nitromethane, a highly flammable substance.

“It was another MH17-style atrocity waiting to happen,” Weiss tells Euromaidan Press. As one of the lead investigators behind the cross-border project that uncovered the GRU’s parcel bomb network, he and his colleagues pieced together evidence that law enforcement across Europe had tried to keep largely under wraps.

The investigation — coordinated across five countries — forced prosecutors and security services to confirm details they might otherwise have kept in secrecy.

The result was a rare moment when journalism, not official communiques, drove the agenda. Speaking to Euromaidan Press, Weiss shares how the story came together — and why Europe cannot afford to dismiss these plots as anything less than war.

Cracking the case

The months-long investigation, published by VSquare and involving journalists from five different countries, began with a deceptively simple question: who was behind a string of parcel explosions and attempted attacks across Europe in July 2025, targeting civilian shopping centers, cargo hubs, and logistics networks across Poland, Lithuania, Germany, and the United Kingdom?

Weiss explains that his team queried law enforcement and intelligence officials, pored over legal documents, and interviewed either the alleged perpetrators or their relatives. What they found shocked them.

“This wasn’t some random assortment of riffraff living in the West,” Weiss says. “It started with a former Soviet submarine commander and his comrades. That shows the GRU is activating networks of more trusted and trained personnel to conduct state terrorism.”

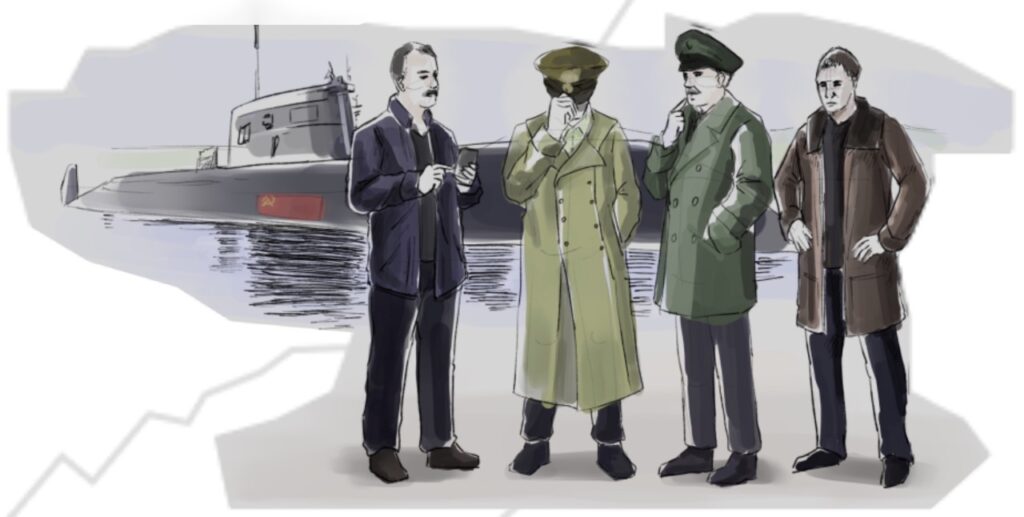

The investigation revealed how four former Soviet naval officers who served together in the Northern Fleet in the late 1980s and early 1990s were reactivated for this operation. At the center was Aleksandr Miroshnikov, a former commander of the K-387, a nuclear-powered submarine that conducted secret missions during the Cold War.

Thirty years after their service ended, Miroshnikov reunited his old crew for a very different mission — one that would circle explosive parcels through Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Moldova, and back again, crossing NATO borders at least five times over nearly a month.

For Weiss, this marked a refinement in Russian methods. After the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, GRU operatives had been unmasked, making it difficult for them to travel in Europe. In response, Moscow relied on Telegram channels, recruiting criminals with promises of “easy money” to vandalize, burn, or bomb targets.

Now the Kremlin was turning to veterans with real training and discipline.

NYT: Russia conducts sabotage operations across Europe to undermine support for Ukraine

Breaking through the walls

Getting to that conclusion wasn’t easy. The investigation involved tracking the explosive parcels’ circuitous route across Europe and identifying the entire network of operatives — from the old Soviet submariners to Ukrainian refugees recruited for transport jobs, to violent ex-convicts handling the assembly of the devices.

“The hardest part was getting law enforcement to talk,” Weiss recalls. “These were still active investigations. The Lithuanian prosecutor was evidently very upset, which is why he called a press conference to announce the conclusions of this case a day after we submitted our final list of questions.”

That press conference, in a sense, was forced by journalism. Where governments hesitated to reveal details, reporters connected dots across borders — tracing the operation back through Telegram handlers to the GRU’s Department of Special Tasks, a unit created in 2023 specifically to respond to Western support for Ukraine.

Why massage pillows, eyeliner, and sex toys?

The investigation revealed disturbing details about how the bombs were constructed and disguised. When Polish authorities intercepted one of the packages before it could detonate, they found Chinese-made neck massage pillows that concealed timing mechanisms and ignition devices in their padding. Cosmetic tubes easily hid the incendiary nitromethane.

Other packages contained sex toys — erotic devices that airport scanners would flag as embarrassing rather than dangerous.

When asked why the GRU used parcels disguised as consumer goods, Weiss answers with a dark chuckle. “Probably because eyeliner and dildos are not typically associated with bombs.”

He’s being sardonic about the cynicism of it all. The choice was calculated: hide explosives in the least suspicious packages possible, items that security personnel might glance past due to awkwardness or routine, while ensuring they passed through airport logistics systems unnoticed.

Thomas Haldenwang, head of Germany’s domestic intelligence service, later told Polish newspaper Wyborcza that “it was just a happy coincidence that the package caught fire on the ground, not in flight.”

From test runs to terror

These were not clumsy trial runs. Weiss calls the campaign evidence of “a growing brazenness.”

The investigation revealed that Yaroslav Mikhailov, a 37-year-old Russian smuggler of radioactive materials operating under the Telegram alias “Jarik Deppa,” had been conducting dress rehearsals — testing how European logistics companies inspected and loaded cargo bound for the United States and Canada, dispatching various packages to probe security vulnerabilities.

“Suppose one of these cargo planes had exploded in midair,” Weiss says. “You’ve now killed the crew and untold numbers of civilians on the ground from falling debris or a crash of a disabled aircraft. As we say in the piece, this was another MH17-style atrocity waiting to happen.”

Russia was prepared to accept civilian mass casualties in its sabotage campaign — terrorism was the point.

A human web of operatives

The network itself looked like something from a Cold War spy novel. At its center: a Soviet submarine commander and his comrades, veterans activated for covert operations. Around them: violent criminals and unwitting participants.

“Quite a number of previous operations involved organized crime networks,” Weiss explains. “The GRU had enlisted an Estonian network to smash up the car of the Estonian Interior Minister and conduct other acts of vandalism in Tallinn. But using a retired Soviet submarine commander is new, almost like a le Carré novel come to life.”

The investigation identified key operatives beyond the old naval crew. Vyacheslav Chebanenko, nicknamed “Ponchik” (donut in Russian) owing to his obesity, was a violent Ukrainian ex-convict who’d served five years in prison for raping his wife.

He assembled the bombs in a Vilnius Airbnb, dividing the original package into four separate parcels, hiding timing mechanisms in massage pillow padding and nitromethane in cosmetic tubes.

Aleksandr Šuranovas, a Lithuanian in his fifties with experience in violent operations, was supposed to ship the bombs — but got lost trying to find the Airbnb. This forced Chebanenko to deactivate the devices and consolidate everything again, sending the operation on a detour through Moldova and Latvia before the parcels finally made their way back to Lithuania.

Other participants included Ukrainian nationals living abroad, some doing it for money.

For Moscow, this was a win-win: operations could continue with plausible deniability, while Europe’s far right could point fingers at “Ukrainian criminals” instead of Russian intelligence.

Disruption and terror: a dual strategy

What was the GRU really trying to achieve with these parcel attacks?

“Some of the documented attacks or would-be attacks are on military or defense installations linked to security assistance or training efforts for Ukraine,” Weiss explains. “So those explanations are rather obvious: the Russians want to stop the West from helping the country they’re trying to conquer.”

But elsewhere, the targets tell a different story. “We see soft targets such as these DHL planes. That looks like terrorism, pure and simply, designed to frighten European electorates, weaken support for Ukraine, and bolster pro-Kremlin political parties.”

Weiss notes that one obstacle in investigating these stories is that some countries don’t want the full extent of these terror operations known for exactly those reasons — public panic could shift politics in Moscow’s favor.

Russian online recruitment of intel gatherers across Europe revealed by investigation

“You will have to be lucky always”

How have European security services responded so far, and are they adapting quickly enough?

“Well, we know everything about this case because of painstaking investigative efforts,” Weiss says. “But remember the IRA line after the failed assassination of Margaret Thatcher, ‘Today we were unlucky, but remember, we only have to be lucky once. You will have to be lucky always.’ And they have been lucky. Look at the IKEA warehouse in Vilnius; the Leroy Merlin store in Łódź; and the shopping center in Warsaw.”

The asymmetry is stark.

“The GRU spends pennies relative to their annual budget to carry out these attacks, putting none of their officers — who are sat at computer terminals in Moscow — at risk. The people getting arrested are plausibly deniable assets. Many are Ukrainian nationals, too, who are doing it for money, but for the Russians this is an excellent outcome as it stokes anti-Ukrainian sentiment on the continent.”

Russia recruits Ukrainian nationals for its sabotage campaigns in the EU, which stokes anti-Ukrainian sentiment

“Europe’s problem — and this transcends the fields of counterterrorism or counterintelligence; just look at NATO airspace now — is that it is always on the backfoot, playing defense. The Russians need to pay a price for these attacks, and pay it preemptively, otherwise they have no reason to stop.”

Stop calling it “hybrid warfare”

What should the EU and its member states be doing differently to counter this kind of warfare?

“First, stop calling it ‘hybrid warfare.’ It’s war,” Weiss insists. “Second, let the Russians know that the Ukrainian services are eager, willing, and able to carry out these kinds of operations on Russian soil, and they have no fear of escalation. What they do have is enormous gratitude for continued Western military and financial support, a gratitude they’d no doubt like to repay in all sorts of imaginative ways, if only someone would ask…”

At a discussion held under Chatham House rules during the 2025 Globsec forum, Euromaidan Press learned that the Ukrainian special services are already sending Russians to Russia to “blow up things on behalf of Ukraine” – operations that western security experts see as effective responses to Russian hybrid warfare.

“Ukrainians are doing certain things against the Russians that are pretty wild. We wouldn’t be doing that if it were us because it’s illegal, but they’re doing them,” a Western security expert said during the panel.

“Maybe they just need a little bit of a nudge from the sponsors. Meaning us,” he added.

The implication is clear: Ukraine has already demonstrated it can strike inside Russia without seeking permission. The question is whether Europe is ready to move from passive defense to active deterrence.

They’ve already recruited more

Will Russia keep trying similar operations, or change tactics now that this network has been exposed?

“One exposed network isn’t going to deter the Russians, I’m afraid,” Weiss says. “They’ve already recruited more.”

The VSquare investigation disrupted one network.

- Vyacheslav Chebanenko, the bomb assembler, sits in pretrial detention in Poland.

- Aleksandr Šuranovas is in a Lithuanian prison.

- Several others have been arrested across Europe.

- But the GRU’s Department of Special Tasks continues to operate, recruiting new assets through Telegram, activating dormant networks, and probing European vulnerabilities.

Unless Europe shifts from reactive to proactive strategy, the parcel bombs and sabotage attempts will continue — and the next near miss could be a catastrophe.

Russia recruits German citizens as “single-use agents” via social media to sabotage Ukrainian military training sites

Why it matters for Ukraine and Europe

The GRU’s parcel bomb operation is part of a broader continuum of Russian sabotage, from the Skripal poisonings to Nord Stream explosions. But the message is tailored for today’s battlefield: frighten European civilians, weaken solidarity with Ukraine, and erode Western resolve.

For Ukraine, this is nothing new. Russia has waged a total war against it for years. For Europe, it is a dangerous awakening. Weiss’s investigation — and his warnings — highlight what Ukraine has long argued: Moscow is not dabbling in gray-zone tactics. It is conducting war by every means available.

Unless Europe adapts, the next “near miss” could be a catastrophe.