A Romanian politician is warning that his country’s economic crisis has become a weapon in Russia’s hands—even as he breaks with his own party to call for sending troops to Ukraine.

Claudiu Năsui, former economy minister and opposition MP, told Euromaidan Press that Romania should deploy forces to prevent Russian borders from moving closer. The stance directly contradicts his Save Romania Union party’s official position and Romania’s government policy.

But Năsui’s bigger concern isn’t about troops. It’s about how pro-Russian voices exploit Romania’s EU-worst inflation with a devastatingly simple lie: “You are poorer because they are helping Ukraine.”

The reality? Romania’s assistance to Ukraine remains far below what it should be, and the country would face identical economic problems even without providing any support at all.

“People are not just poor—we have always been relatively poor—but now they are getting poorer,” Năsui explained. “When you have such an economic climate and a government that is pro-NATO, the risk is that people start making a false connection between the two.”

With parliamentary elections in 2027, sustained economic problems could shift political outcomes. But institutional safeguards provide near-term protection: Romania’s staunchly pro-Ukrainian president controls foreign policy for the next five years.

Romanian MP defies party line with call for military deployment

Claudiu Năsui declared that Romania should send troops and argued that his country should provide far greater assistance to Ukraine, emphasizing that preventing Russian borders from moving closer represents a vital Romanian interest.

“I think Romania should send troops. I believe we should help Ukraine far more than we have up to now. It is a vital Romanian interest not to have Russia on our border,” Năsui declared, breaking sharply with his party’s official stance against putting “boots on the ground.”

The former minister argued Romania’s current position reflects luck rather than strategy.

“The fact that you bordered Russia rather than us was, frankly, luck—bad luck for you and fortunate for us. We should not rely on luck. Because we were lucky, we owe it to ourselves and to the region to help you succeed.”

Năsui also criticized Romania’s passive response to Russian violations. When a Russian drone recently entered Romanian airspace and was escorted back rather than destroyed, he argued Romania should have shot it down, citing Türkiye’s more assertive approach.

“This is how a sovereign nation with a functioning military responds,” he said. “It is in Romania’s fundamental interest for Ukraine to win this war.”

The Save Romania Union officially opposes troop deployment and peacekeeping missions on Ukrainian soil, making Năsui’s position a significant internal dissent within the reform-oriented party that typically champions strong pro-European positions.

Economic crisis becomes weapon for Russian information warfare

Romania’s domestic economic pressures are creating dangerous openings for pro-Russian propaganda, according to Năsui’s analysis. With EU-high inflation hammering Romanian households, hostile voices exploit the pain with a devastatingly simple narrative.

“People are not just poor—we have always been relatively poor—but now they are getting poorer. Things are getting worse, not better,” Năsui explained.

“Prices are sky-high, and people are struggling enormously to make ends meet. So when you have such an economic climate and, at the same time, a government that is pro-NATO, the risk is that people start making a false connection between the two.”

Pro-Russian voices actively promote this false connection: “You are poorer because they are helping Ukraine.”

But reality contradicts the narrative. “The assistance Romania has provided to Ukraine is actually far too little compared to what it should have been,” Năsui noted.

Năsui argued that Romania would still be confronting the same deep structural economic problems even if the country had provided no financial assistance to Ukraine whatsoever.

“Even if Romania had not given a single cent to Ukraine, we would still be facing the same deep structural economic issues.”

The political risk is real. “People start to assimilate one with the other: the government is pro-NATO, life is getting harder, therefore the two must be connected. And that, I believe, is the real danger.”

With parliamentary elections scheduled for 2027, sustained economic problems could shift political outcomes.

“If we want to secure victory for these ideas and this course of action, then we must address our economic problems now,” Năsui warned. “Otherwise, the risk becomes very real that in three years’ time, the political outcome could shift.”

Institutional safeguards provide near-term protection

Despite economic pressures, Romania’s constitutional structure provides significant protection for pro-Ukrainian policies, according to Năsui’s institutional analysis.

“Let me reassure you on one essential point. Regardless of how solid or fragile the current coalition may be, foreign relations, foreign policy, and the military fall under the prerogative of the president,” he explained.

Năsui explained that the president holds significant power and noted that Romania currently has a staunchly pro-European, pro-Ukrainian president.

“The president holds significant power, and right now we have a staunchly pro-European, pro-Ukrainian president.”

This means “for the next five years—unless something truly unforeseen occurs—things will remain stable in this regard. Romania is a reliable partner.” But the protection isn’t absolute if economic problems persist.

Sanctions evasion explodes through obvious trade manipulation

Romanian and EU authorities are allowing massive sanctions evasion through transparently artificial trade relationships, Năsui revealed in harsh criticism of enforcement failures.

Năsui revealed that trade between Romania and Kyrgyzstan was virtually nonexistent before February 2022, with almost no exchanges between the countries. He pointed out that after the war began and sanctions were introduced, this trade suddenly exploded, describing the pattern as obvious sanctions dodging that was transparently clear.

“Before the war, before February 2022, trade between Romania and Kyrgyzstan was virtually zero. We had almost no exchanges at all. After the war began and sanctions were introduced, suddenly that trade exploded. How is that possible? It is sanction dodging—and it’s so clear and so obvious.”

The pattern extends beyond Romania, with multiple EU countries allowing similar circumvention through Central Asian transit states. “Yes, I have been very critical of our government for allowing this to happen. We are not doing enough, we don’t have the necessary safeguards, and we are not treating this war with the seriousness it requires.”

Romania-Kyrgyzstan trade explosion points to sanctions evasion

2024 ██████████████████████████████████ $38.1M

2023 ███████████ $10.5M

2018 ██ $2.5M

Data: Oec.world

Năsui attributed enforcement gaps partly to lingering Russian-aligned interests within Romania’s Social Democratic Party, pointing to politicians with “links either to the former Communist Party—which was deeply intertwined with Russia—or to economic interests connected with authoritarian regimes.”

The pattern extends beyond current sanctions. “Even before, there was another Social Democratic prime minister who wanted to build a second nuclear facility at Cernavodă with Chinese companies, essentially tying Romania closer to China,” Năsui noted, illustrating how these networks consistently promote policies that weaken Western integration.

Ukraine leads global defense innovation as NATO lags behind

Ukraine’s rapid transformation of its defense sector offers crucial lessons that Romania and other NATO allies are failing to absorb, Năsui argued.

“One of the first things I noticed happening very quickly in Ukraine after the war began was the opening of the defense sector to private capital, essentially a kind of privatization of the military industry,” he observed. “In Romania, most of our defense industry is still state-owned, and frankly, it performs very poorly.”

The results speak for themselves. “Right now, I think it was General Cavoli who said that Ukraine probably has the most advanced drone industry in the world. And that is because Ukraine has hands-on, real battlefield experience.”

Ukraine’s advantage comes from rapid iteration:

“It’s not just about having years of research into a microchip—it’s about developing systems that are manufactured, deployed, and battle-tested, with constant feedback loops and rapid error correction. Ukraine has this ecosystem, and that is invaluable.”

Romania should integrate more closely with Ukrainian defense innovation and pursue joint drone production initiatives, Năsui argues, since “our potential enemies are the same. Romania is not going to start a war with Bulgaria or Hungary. Our defense mission is focused squarely on Russia—both on land and in the Black Sea.”

In naval warfare, Ukraine has shown how innovation overcomes conventional disadvantages.

“Without even having large naval vessels, you managed to sink the Moskva and several other Russian ships, effectively keeping the rest of the Russian fleet at bay. You created a large interdiction zone where Russian ships simply cannot operate without risk of attack.”

Regional security challenges demand post-war resolution

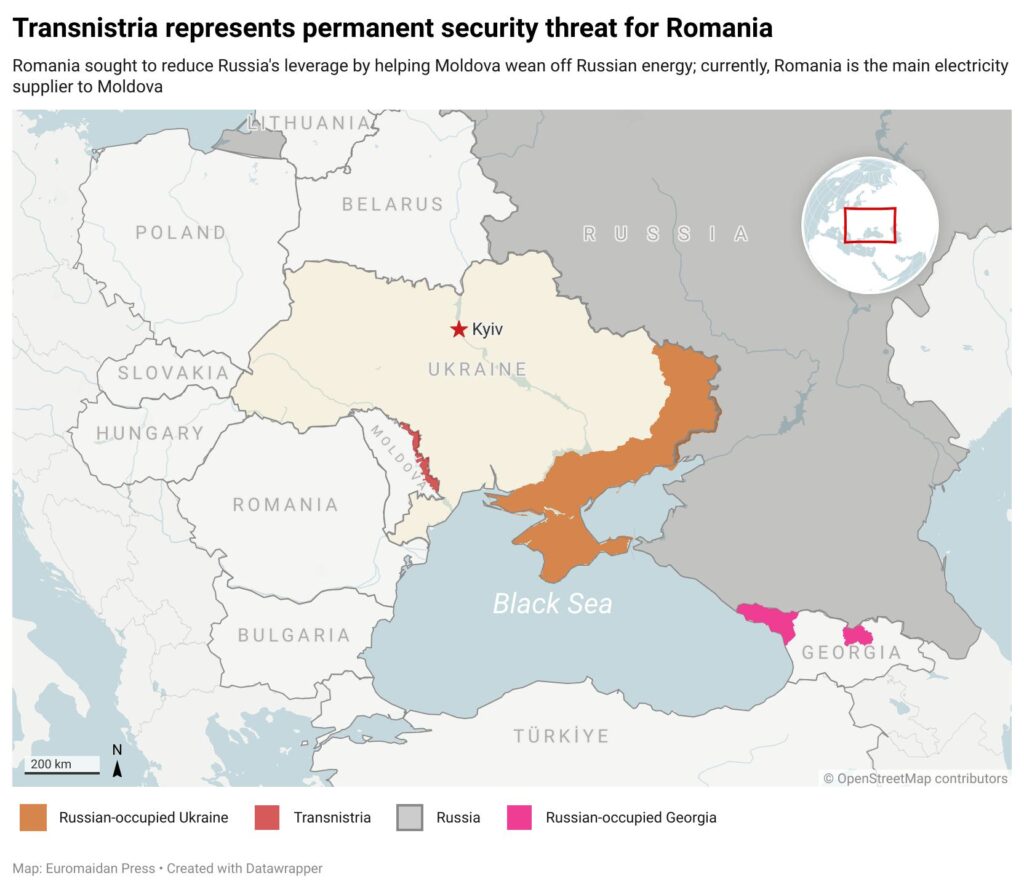

Russian military presence in Moldova’s breakaway Transnistria region represents a fundamental obstacle to regional security that must be addressed after the war, Năsui argued.

Năsui argued that both Ukraine and Moldova face the same fundamental challenge of Russian troops stationed on their territory, emphasizing that this situation cannot remain unresolved and must be addressed after the war ends.

“Both Ukraine and Moldova face the same fundamental challenge: the presence of Russian troops on their territory. That situation cannot remain unresolved. It will have to be addressed after the war,” he said.

“True integration—whether into the European Union or broader regional frameworks—cannot be achieved while you still have Russian military forces stationed in places like Transnistria.”

Romania has made progress reducing Russian regional leverage through energy independence.

“This is why, two or three years ago, we completed the interconnection of Moldova’s energy grid with Romania’s. Now, Romania is the main energy provider to Moldova, which means Moldova is no longer dependent on Russia for electricity supply.”

Natural gas dependence remains “a more complicated issue,” but electricity independence provides a crucial foundation.

Regarding Hungary’s continued obstruction of Ukraine support, Năsui offered a pessimistic assessment based on his ministerial experience with Hungarian leadership.

“I’m not sure you actually can—and I’ll tell you why. There’s a saying: you can’t convince somebody of something if they have an active interest in not being convinced. Hungary is dependent on energy imports from Russia.”

The stakes for democratic resilience

Năsui’s warnings reflect broader concerns about democratic resilience across Eastern Europe, where economic pressures and Russian information operations work together to undermine public support for continued resistance to Moscow’s imperial ambitions.

He concluded by warning that although the three-year timeline might appear distant, and people often dismiss future problems as not requiring immediate attention, any delay in addressing these challenges would render solutions ineffective.

“Three years may sound far away, and many people think: ‘If it’s only a problem in three years, why care now?’ But if you only start caring then, it will already be too late,” he concluded.

The assessment suggests that Romania’s contribution to European security depends not only on continued political commitment to Ukraine support, but on successful domestic economic management that maintains public support for strategic positions over the extended timeframe required for Ukrainian victory.