It is a good day for Ukraine and Europe.

On 23 February, Germany held snap elections following Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s announcement in November 2024 that the 2021 coalition between the Social Democrats (SPD), Free Democratic Party (FDP), and the Greens had collapsed.

While the official votes are being tallied, the exit polls indicate that the Conservative CDU/CSU party, formerly led by Angela Merkel, secured around 28.5% of the public vote, with its new political star Friedrich Merz, a pro-Ukraine politician who was spotted watching Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s press conference when the first results flowed in, announcing his victory.

Meanwhile, his opponent, Scholz, a figure whose track record has been mixed, including in the Russia-Ukraine war, admitted his defeat and took responsibility for it.

Merz’s chief competitor, Alternative for Deutschland (AfD) led by Alice Weidel, ended up in the second place, with its support standing at around 20% mostly in parts of Germany that were Soviet controlled until the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

The ruling SPD secured around 16% of the votes, the Greens – 11.9% and the Left – 8.6%

Merz has already made it clear that he will seek a quick coalition fix as “the world won’t wait for lengthy talks,” and is awaiting the results of the smaller parties that could be part of it, particularly FDP.

The results of these elections are paramount not just because Merz is avidly pro-Ukrainian and believes that Ukraine should be part of the ongoing peace negotiations but also due to their becoming the peak of decade-old policies, the ramifications of which tainted the European political scene and allowed Russia to interfere.

The echoes of 2015

Much of what is happening in Europe today, including the resurrection of the right-wing ideology that has become normalized all over the continent, takes its root in 2015.

Back then, the European Union (EU) faced the stark prospect of accepting hundreds of thousands of refugees, mostly Syrians fleeing the destroyed country, as well as Afghans and Iraqis, who arrived in Europe en masse.

The chaos of those days was evident not just in media reports, but on the ground too, with liberal strongholds like Sweden, led at the time by social-democrat PM Stefan Löfven, installing border checks at Hyllie, the first stop in Sweden that connects it with Denmark, via the Oresund Bridge. It was used as a gateway by the majority of refugees arriving in the country.

While Sweden had the third-highest number of asylum applications in 2015, it was Germany that really took the hit, receiving an unprecedented 442,000 individual first-time asylum applications in 2015 – the highest annual number ever received by a European country in the 30 years before that.

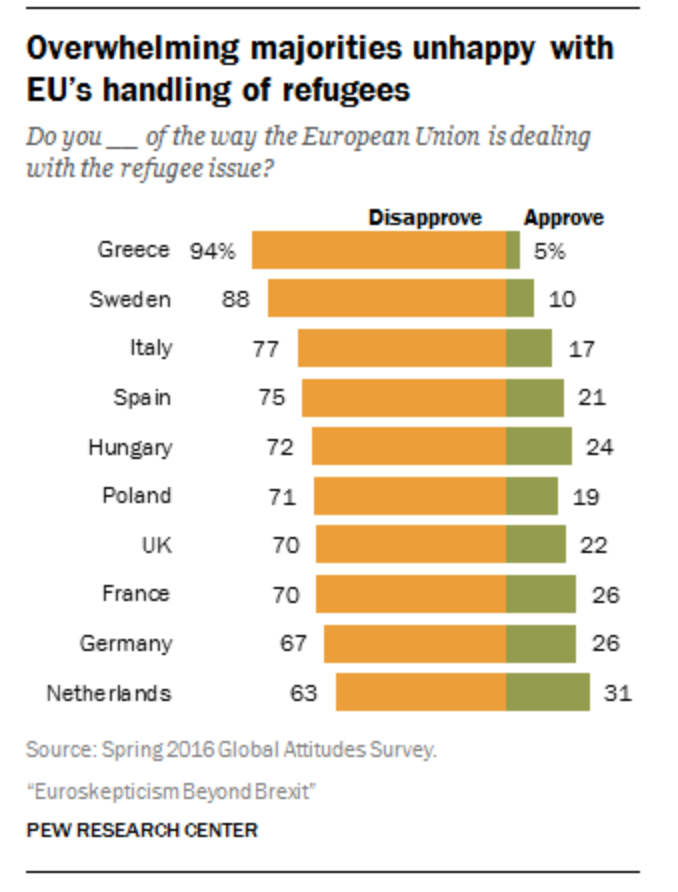

Nonetheless, Merkel took the decision to accept most of these people, which turned out to be a time-ticking bomb, as already in 2016, people expressed high levels of dissatisfaction with how the refugee crisis was handled. This includes 67% of Germans who disapproved of the policies and only 26% approving.

Enter the AfD, a marginal party founded in 2013 that gradually picked up pace. It campaigned predominantly on the much-popular slogans of Euroskepticism, championed at the time by the U.K. and especially the leader of the now-bygone party UKIP, Nigel Farage, who advocated Brexit.

The party’s name effectively opposes Alternativlosigkeit, German for “there’s no alternative” and Merkel’s policy approach that was uncontested by other mainstream parties.

Then came the Brexit vote in 2016, which showed the Euroskeptic parties that their aspirations were realistic. This is especially true given that the former UK PM David Cameron effectively caved into the demands of the hardliners who long opposed London’s EU membership due to its federalist ambitions and immigration.

Combined, these developments served as a turning point for AfD. Already in 2016, the party secured significant successes in local elections at the expense of CDU due to Merkel’s refugee policies and continued to do so alongside other right-wing parties across Europe that started to spring up aggressively, like the Italian Lega party led by Matteo Salvini. Or feel emboldened, prompting the center-right parties across the continent to adapt to the new reality. This is best illustrated in Sweden, where the now-ruling Moderaterna is much less center-right than it used to be, and is collaborating with the far-right Swedish Democrats, a once unimaginable scenario for the Swedish political setup.

Breaking away from Merkel’s legacy

Given these developments, it was only a matter of time before the sentiment in Merkel’s own party would start to change too.

After the results of the 2021 vote, which saw the Social Democrats win the election, change became inevitable, and Friedrich Merz became the top option to lead the new, more radical, and determined version of the party.

Born in 1955 into a conservative Catholic family in the North Rhine-Westphalia town of Brilon, he became interested in politics while still in school. In 1989, aged 33, he was elected to the European Parliament before eventually entering the Bundestag in 1994 following the parliamentary election.

During many years, he would promote much more Conservative ideas compared to the other rising political star of Merkel, with which he had an ever-growing feud, especially after she won the election in 2004, one year after Merz famously argued that German tax rules should be simple enough to calculate on the back of a beer coaster.

Later, he even plotted a political conspiracy against her as part of the so-called Andean pact, a group of party members who took a particular dislike to the Chancellor before leaving politics and joining the private sector in 2009, working as a lawyer and senior counsel at the international law firm Mayer Brown, among other positions that turned him into a multi-millionaire.

But as the mantra goes: “Once a politician, always a politician.”

Already in 2015, Merz publicly criticized Merkel’s “open door” refugee policy, dubbing it a grave error. Then the decision to return to politics was taken, though things did not turn out to be seamless.

Despite enjoying support from Wolfgang Schäuble, one of the chief creators of Merkel’s austerity policies introduced following the 2007-2008 economic crisis, he did not win the 2018 party leadership election. It took him several attempts to succeed before he became the party leader on 31 January 2022 with the clear-cut goal of wrestling back votes from AfD, the popularity of which was evident in the 2021 election when the party secured 83 seats due to other parties’ lack of response to pertinent issues like immigration among others.

This was further evident in the local elections held in September 2024, during which the AfD received around 33% and 32% of the vote in the eastern German states of Thuringia and Saxony.

The reason for this rise was explained by Benjamin Tallis, a former member of the German Council on Foreign Relations who participated in EU security missions in Ukraine and the Balkans, who rejected the idea of the results being associated with the aid to Ukraine, emphasizing that people feel like “they’re not being listened to when it comes to inflation, migration” and “that the government have not had good answers to, to be honest, and have tried to ignore as best they can.”

No AfD in the coalition

Germany is a parliamentarian republic with a Bundestag threshold of 5% that requires parties who enter it to form coalitions to prevent any party from dominating the political life and thus avoid the mistakes of the past.

Their format varies over the years, but the winners are always obliged to cooperate with either smaller parties like the FDP, which, according to the exit polling, has not passed the 5% barrier, or established players like the CDU/CSU and the SDP. Such coalitions are usually referred to as grand coalitions, which will likely be created this time, though other options, like a minority government, are also on the table.

It is for this reason that despite reportedly securing 20%, the AfD will highly unlikely be part of the government, especially since Merz, on several occasions, ruled that possibility out—though they share some talking points with Weidel and previously collaborated. In January, Merz pushed through an immigration bill with help from the AfD, a move that garnered criticism from Merkel, who said that his party crossed a red line by allowing a migration policy motion. The bill ultimately failed through.

However, when it comes to security, the ideological alliance between Merz and AfD ends.

Unlike Merz, AfD is not supportive of Ukraine and is generally believed to be Russia sympathetic if not outright Russia-sponsored and has some worrying Nazi elements to it.

Its leader Alice Weidel rejects the idea of providing aid to Ukraine, let alone helping Ukraine win, and wants to restore Putin’s pet project Nord Stream 2, a move that would effectively reverse Germany’s decreasing dependence on Moscow’s fossil fuels in the past several years after years of consciously building up its reliance on Putin’s regime and filling Russian coffers.

Given such sympathies toward Moscow, it is hardly a surprise that a Russia-linked pro-AfD disinformation campaign was launched just before the election, with fabricated videos circulating claiming that ballots in Leipzig are missing the name of the AfD candidate and that machines are shredding ballots cast for the AfD.

During a televised debate, Merz went further in criticizing Weidel for her Russia-friendly position, saying that Germany isn’t neutral in the Russo-Ukraine war as it stands with Ukraine.

Entering Trump era

Merz’s victory comes at a time when the US has made it explicit to Europe that it is no longer willing to foot the European security bill, which is a result of decades-long US’s post-WWII priorities shift.

When the Cold War ended, and capitalism prevailed, the unraveling of the system started to expedite further, with Bill Clinton campaigning in 1992 on the pledge to focus far more on “the economy, stupid” than on foreign policy, which was in the eye-apple of George Bush’s administration alongside other foreign policy hawks like Dick Cheney and Condoleezza Rice.

The West’s desire to cooperate with post-Soviet Russia likewise played a role, especially with its new and young leader at the time, Vladimir Putin who in 1999 replaced President Boris Yeltsin, the man responsible for the economic chaos of the 1990s and the formation of the oligarchy class in Russia.

The purpose of the anti-USSR NATO in this new setup, where nuclear weapons were disposed of and the feeling of cooperation prevailed, was not immediately understood. Nor was there sufficient appetite to acknowledge that Russia had not fundamentally changed but was simply weaker than before.

Neither Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 nor the occupation of Crimea and the Donbas in 2014 was able to change it, including in the US that started to focus far more on the Pacific region, often cozying up with Russia as well for puzzling reasons. Take President Joe Biden’s decision to lift Trump-imposed sanctions on Nord Stream 2, roughly half a year before Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

During his tenure between 2017-2021, US President Donald Trump only served to galvanize these changes when he clashed with the European allies over their spending in NATO, which he views as a purely transactional organization.

Trump administration’s current attitude to Europe is the continuation of that policy, though it comes in a much less diplomatic and at times, frankly put, inappropriate format of public scolding and blackmail. This was particularly the case with US Vice-President J.D. Vance’s speech at the Munich Security Conference where he effectively lambasted the European Allies for not handling freedom of speech the way the US sees it fit, i.e. where there’s no single arbiter of truth, before leaving the stage with little applause and later meeting Weidel, who’s also aggressively promoted by tech mogul Elon Musk.

Knowing Merz’s political orientation, there’s a great chance that he could have sympathized with some of Vance’s speech parts, especially his strong criticism of uncontrolled immigration, which he likewise opposes and is set to appropriate in the coming years in terms of policy handling. This could be grounds for cooperation between Berlin and Washington D.C. in the next four years, especially since Trump’s officials make no secret of their ambition to restore “the greatness of Christian civilization” and Trump writing a good dose of praise on Truth Social toward the Conservatives following their victory (and himself too).

But how far this collaboration will go is a very open question as Merz has taken a hard stance against Trump’s remarks toward President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, whom, in his Truth Social rant, he dubbed a “dictator” and made it clear that he believes Ukraine’s President could have prevented the war by striking a deal even if Donald Trump weren’t around (if he were, this “war would have never happened.”)

Merz qualified such rhetoric as “echoing Russian propaganda” and said he was “shocked” by it.

Beyond the remarks, it is the reformed security architecture that will become key in the relations between Berlin and Washington D.C.

Despite being a country physically affected by the Cold War in the form of the Berlin Wall, since the 1990s, Berlin has taken a lax approach to defense spending, much to the frustration of many, including Trump, who accused Germany in 2018 of benefitting from the Russian gas dependency while seeking protection from Moscow.

Biden was less confrontational, giving Berlin some time to go back to business as usual before Russia launched the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and dramatically changed the situation in Europe. As a result, the two largest European economies, Germany and France, are now spending 2.06% and 2.12% of their GDP, after Germany failed to hit the target for almost three decades, reaching the level of 2% only in early 2024.

But this is not enough. Not just because Trump has rolled out the 5% NATO spending target, but because it doesn’t correspond to the needs of the reality on the ground.

Whatever the outcome of Trump’s peace push in Ukraine, which, according to some of our sources in Washington D.C., is far more complex behind the scenes than publicly presented, including far less nice conversations between Trump and Putin, Europe can no longer escape the responsibility of self-care.

This realization has apparently already sunk in Paris and London as they head to meet Trump in Washington D.C. on Monday, presenting their rudimentary vision of the peacekeeping mission in Ukraine.

But without Germany stepping up, the possibility of true and much-needed change is questionable. Germany is the richest economy in the EU, so any increase it takes is far more significant money-wise than that of Estonia, even though the Baltic States are impeccable in terms of support.

Merz’s position on this isn’t fully clear as he stated that the “2, 3 or 5% (targets) are basically irrelevant, the decisive factor is that we do what is necessary to defend ourselves.” It is likewise unclear what will happen to Merz’s promise to supply Taurus missiles to Kyiv, a pledge that he slightly softened at the Munich Security Conference, saying that while he supports the idea, he must first consult with the U.K. and France.

Regardless of the unknowns, one thing is giving Europe and Ukraine a good dose of optimism: Germany will now be most likely headed by a man who made this statement on TV right after the exit polls: “The primary priority of this government will be to ensure that Europe can achieve full strategic independence from the United States in the defense against Russia.”

And it appears that he means it.

This story is being updated.