“Thousands of killer drones that will hunt people around the clock are no longer a matter of decades. It is a matter of literally months. I understand that this sounds like a fantastic horror movie. But in my opinion, this is our reality, coming as soon as next year, in 2026,” writes Maria Berlinska, a Ukrainian human rights activist and founder of the Victory Drones program.

On 17 July 2025, the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine published a report titled “Deadly Drones: Civilians Under Threat from Short-Range Drones in Frontline Areas of Ukraine.”

Just a week before that, on 9 July 2025, a Russian drone killed a one-year-old boy, Dmytro, in a targeted attack on the village of Pravdyne, Kherson Oblast.

Photos of this crime went around the world, making it onto the cover of the New York Post.

“Moscow is turning Kherson into a ‘human safari zone,'” the publication reported.

Human safari is the chilling definition of life in Kherson, coined by the city residents themselves. American writer and journalist Zarina Zabrisky was the first to report on the human safari in international media in July 2024.

While producing numerous reports, commentaries, and interviews, she worked on a book about the Kherson Oblast during Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, as well as a documentary film to open the eyes of global audiences to a reality more cruel than dystopia.

Filming lasted from September 2023 to June 2025. The documentary Kherson: Human Safari is now available for free viewing to raise awareness about this unprecedented form of warfare.

The story of Kherson

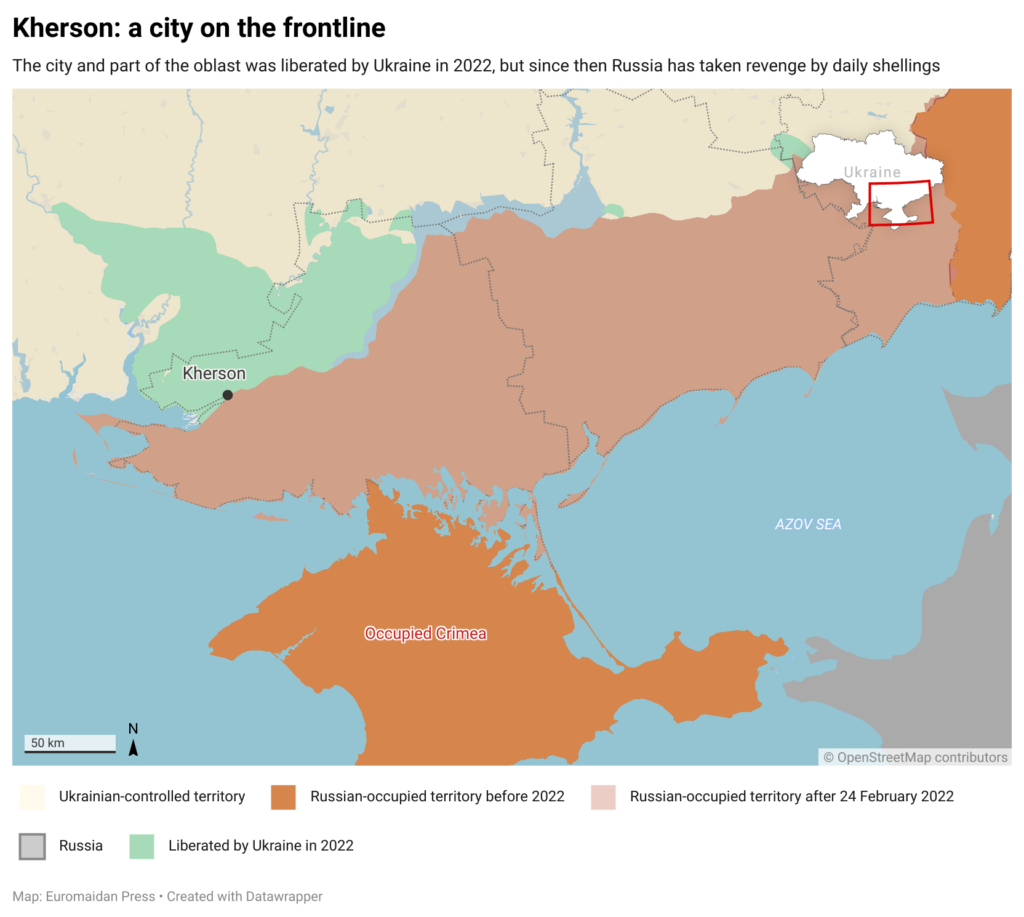

Kherson became the only Ukrainian regional center that Moscow managed to capture since 2022. The Russian occupation lasted almost nine months. The liberated city and its residents quickly became the object of furious revenge by the invaders, forced to retreat to the left, eastern bank of the Dnipro River.

Fleeing from Kherson, Russians blew up the infrastructure, leaving residents without electricity. Later, they began shelling with artillery, missiles, and guided bombs.

“Every shot we hear from the left bank brings grief and trouble,” says one of the central characters of the film Kherson: Human Safari.

Zarina Zabrisky arrived in Kherson with other war correspondents on the third day after the de-occupation.

“This first visit to the city turned out to be the most memorable in my life. Maybe even the most memorable day in my life,” Zabrisky recalls in an excerpt in Chronicles of War: February 2022 — February 2023, published by the Ukrainian publishing house Folio. The writer was struck by the joy of Kherson residents who celebrated freedom,

“I have never seen so many ways of wearing national flags and outfits in national colors, and I, mind you, am from America, where this is a national sport.”

It was then that Zabrisky gathered the first testimonies about the occupation from Kherson residents: torture chambers, intimidation, child abduction, the farce of the referendum on joining Russia, mass burnings of corpses in mobile crematoriums and in landfills, the smell of charred human skin and hair.

“I couldn’t look up. I walked with my head down all the time,” says the central character, recalling the months of Russian rule.

“They swam through the windows…”

Among those who agreed to a conversation on camera was artist and writer Alyona Maliarenko. She described the experience of Kherson residents in her book Giselle and the World, or How to Survive the Occupation. She wrote about the state of the city after the Russians left:

“Each district suffered in its own way. The multi-story residential neighborhood of Tavryk froze without electricity. There was no gas and people cooked food on fires in the yards. Ostriv and the Skhidny neighborhood shuddered from hourly shelling.”

“In Richport, people were constantly moving like ants near the piers, collecting water from the Dnipro and transporting it around the city, until Russian snipers started shooting at them like at targets in a shooting gallery.”

“In the center of the city, Starlink Internet was distributed in the squares. Hot food points, and later registration points for humanitarian and financial aid, medicine, clothes and stoves multiplied. People were constantly milling around there until Russian surveillance drones started circling above them, attacking the crowds.”

In the film Kherson: Human Safari, Maliarenko, telling the story of the flood after the Russians blew up the Kakhovka hydroelectric power station, mentions her aquarium with goldfish and guppies.

“My house sank. The only ones who were not immediately physically injured were the fish. They swam around my apartment for a week, and then they swam through the windows into the Dnipro.”

The artist’s sense of humor saves her in tragic situations. Humor and self-irony occupy a prominent place in Ukrainian culture and identity as a means of resisting imperial pressure, devaluation, prohibitions, and repression. The same goes for a passion for well-being and beauty.

Alyona Maliarenko is engaged in Samchykivskyi painting, a decorative style that imitates the folk tradition of Volynia. The artist creates virtuoso works and prints them on silk scarves. One of them, called Pisces. Sunny Pool, is dedicated to the fish experience during the flood.

Another central character of the film is the composer Borys Hoina. During the occupation, he became a partisan and gathered information, riding around the city on a bicycle and filming Russian military equipment with a phone in his pocket. Back home, he wrote music on his electric piano, putting his experiences into his compositions.

Zabrisky heard him playing this music at an art event in a shelter in Kherson. Under Russian missile terror, the social and cultural life of Kherson, like in Kharkiv and other frontline cities of Ukraine, moved underground.

Lectures and master classes, concerts and performances are held in shelters. In Borys Hoina’s work, Zabrisky found the most harmonious music for the film.

The Director of Photography, Oleksandr Andriushchenko, is also a native of Kherson, a well-known photographer in the city.

Sacred rituals of making borsch

Respect for the real is inherent in Zabrisky’s documentary, as behind it is a sincere and personal interest in truthful details. The writer and producer came to Ukraine from San Francisco in search of her roots in 2021. She found a building in Uman, where her Jewish great-grandfather and great-grandmother on her paternal side once owned a business.

After Zabrisky’s grandfather was born, they moved to Odesa, where they were killed in the Holocaust. Yet, some relatives survived, and Zabrisky spent summer vacations in Odesa as a child.

“I recently learned that my Ukrainian maternal great-grandmother was born in Pryluky, Chernihiv Oblast,” the filmmaker shared.

Zabrisky perceived the escalation of Russia’s war against Ukraine in 2022 as an attack on her own history. As soon as she could, she started to work as a war correspondent, reporting from the land of her ancestors.

For a while, she even kept her exact location a secret from her loved ones in the United States. To keep them from worrying about her safety, she answered about her whereabouts without sharing details, “In Europe.”

In 72 minutes, the drama of human trials, hopes, resistance, and dignity unfolds before the audience of Kherson: Human Safari. The chapters correspond to the events:

- Invasion.

- Occupation.

- Protests.

- Liberation.

- Shelling.

- Flood.

- Human Safari.

But the main arc of the narrative is not in chronology. It is in the careful, meticulous recording of what the Kherson residents share with the author.

Endurance and solidarity, despair and pain, heroism, hope, and creativity. Talking about loved ones killed by the Russians, a servicewoman cooks borscht. For a Ukrainian woman, making borscht is always an art. Each one is proud of her family recipe.

The immediate threat of death turns this everyday act into a sacred ritual, an affirmation of life despite everything.

Unprecedented form of dehumanization

Zabrisky does not shy away from harsh shots and evidence. She includes drone footage that captures the hunt for civilians near shops and in their cars. Yet, the horror is not the focus here. The tone of the film is far from sensational because it tells the story about the everyday life of Kherson.

This realization causes a certain resistance in a viewer who is presented with a degree of dehumanization not depicted in the most brutal dystopias. A lot of science fiction, from The Hunger Games to Squid Game, is dedicated to human bloodthirstiness, while a lot explores a war of machines against people or an alien invasion.

But people killing helpless, unarmed people as if it were a video game is a new and shameful idea. Human Safari dehumanizes those who play such a game.

In his 1962 work The Gutenberg Galaxy, Marshall McLuhan argued that the invention of the printing press fundamentally reshaped human consciousness, ushering in an era of linear thinking and rational discourse. The decline of the Gutenberg Galaxy, to which writer Zarina Zabrisky remains loyal, is unfolding in ways even more dire than McLuhan once predicted.

The revival he foresaw of primal emotional outbursts and the beating of drums is today amplified by the informational carelessness of millions of social media users. And to that has now been added the new fine motor skills of joystick users.

The latest technologies, combined with the Russian cultural tradition of the law of force and the devaluation of human life, have opened the door to an unprecedented form of inhumanity—human safari.

“When civilization is in decline, and your city is in ruins – what do you do to survive… and remain human?” asks Zarina Zabrisky. In her film, the answer is the words, reactions, and acts of Kherson residents. Yet, this question concerns everyone today.