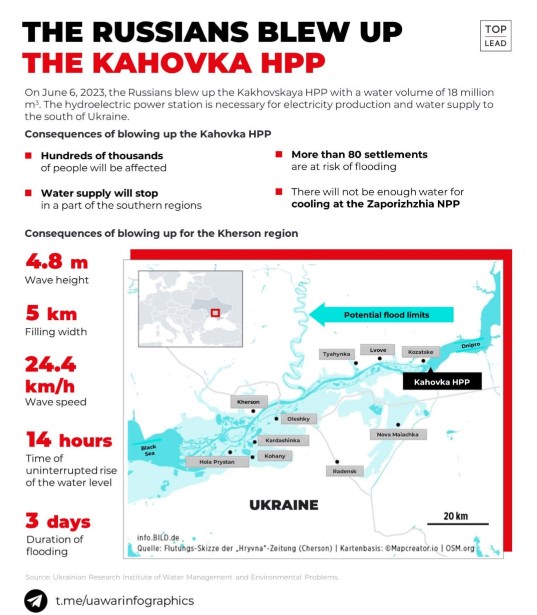

The water began rising quietly, like a whisper. On the morning of 6 June 2023, residents of Oleshky in Kherson Oblast watched small streams seep through their streets. This happened after Russian troops pulled the trigger and blew up the Kakhovka Plant’s dam to prevent a Ukrainian military advance across the Dnipro. What they unleashed that day terrified scientists.

By evening, a 4-meter wall of water had swept away everything in its path. But as the floodwaters receded weeks later, they left behind something far more sinister than destroyed homes and drowned livestock reaching the Black Sea.

“We know that garbage and heavy metals from the bottom of the Kakhovka reservoir didn’t go anywhere—they settled on the sea floor, and during storms they rise again to the upper layers of seawater,” warns Yulia Markhel, leader of the ecological movement Let’s do it Ukraine.

What the water carried from the reservoir’s depths would prove to be one of the most severe environmental disasters of the 21st century, a toxic legacy that had been accumulating in silence for over 60 years, the Ukrainian National Ecology Center reports.

The sleeping giant awakens

When Russian forces destroyed the Kakhovka Dam exactly two years ago, they unleashed 18 cubic kilometers of water in just four days. But the water was merely the messenger. What it carried would transform the Black Sea ecosystem for generations.

Local resident Liudmyla Boretska watched the catastrophe unfold from her rooftop refuge.

“Everything was flooded—cemeteries, garbage dumps, cattle burial grounds. Everywhere there were mosquitoes, the smell of death, horrible screams of people and animals, she told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

But beneath the visible horror, something hidden and far more dangerous was stirring.

The destruction exposed lake bed sediment containing more than 90,000 tons of dangerous heavy metals, a toxic cocktail that had been quietly accumulating on the reservoir floor since 1956.

For decades, industrial waste from mines and factories across the Dnipro basin had settled into the sediment like layers in an archaeological dig.

Each year brought new deposits: manganese, arsenic, lead, cadmium—the metallic signatures of Soviet-era industry.

The contamination spreads

Within days, the contaminated flood surge reached the Black Sea, impacting more than 50% of the northwestern Black Sea area. Satellite imagery revealed a massive brown plume spreading across azure waters, carrying decades of accumulated poison.

Viktor Komorin, who studied fish, mussels, and dead dolphins for toxic substances after the disaster, discovered the true scale of contamination.

“In mussels we found toxic substances exceeding the norm by thousands of times,” he reported.

The filter-feeding mollusks had become living repositories of decades of industrial waste.

What lurks beneath

A couple of days later, all this pollution began reaching the shores of Romania and Bulgaria. Freshwater from the Kakhovka Reservoir entered the Black Sea about 3–4 days after the dam burst and reached the coast of Odesa, reducing the normal salinity of the seawater from the usual 17–18‰ to just 4‰.

The contaminated sediments stretched across 620 square kilometers of exposed lake bed—an area larger than many European cities. In this toxic wasteland, previously absorbed heavy metals were absorbed by vegetation and animals and moved through the local food web.

Historical echoes from depths

As the waters receded, they revealed more than industrial poison. Kherson historian Oleksii Patalakh describes what emerged.

He says the area where the reservoir once stood was a true natural treasure—the green lungs of southern Ukraine. It was a system of rivers, lakes, and islands with incredibly diverse flora and fauna and vast fish stocks, including sturgeon, Suspilne reports. He explains that sturgeon disappeared from the Dnipro after the Kakhovka Reservoir was created.

“In addition, this territory is an archaeological landmark. It includes about five of the eight Zaporizhzhian Sich strongholds. There are fortresses from the time of the Late Scythians, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Ulus of Jochi, more commonly known as the Golden Horde,” he continues.

There were many ports and fortresses on the islands, such as on Tavani Island, between Beryslav and Kakhovka. There were two satellite fortresses: Mustrit-Kermen, which was connected to Gazi-Kermen, and Mubarek-Kermen, which was connected to Islam-Kermen, present-day Kakhovka.

He adds that shortly after the water receded in 2023, specialists in the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast discovered the remains of a submerged Sich-era church, reconstructed in the early 19th century — the site of Nova Sich.

Patalakh emphasizes that the territory from Khortytsia and downriver lies Zaporizhzhia, the historic land of the Cossacks, Ukrainian national warriors-heroes. According to him, these are ancient Cossack territories, home to many winter settlements and numerous submerged Cossack cemeteries. On the one hand, the water could destroy all this. On the other hand, researchers now have the opportunity to study these objects of historical heritage.

The reckoning ahead

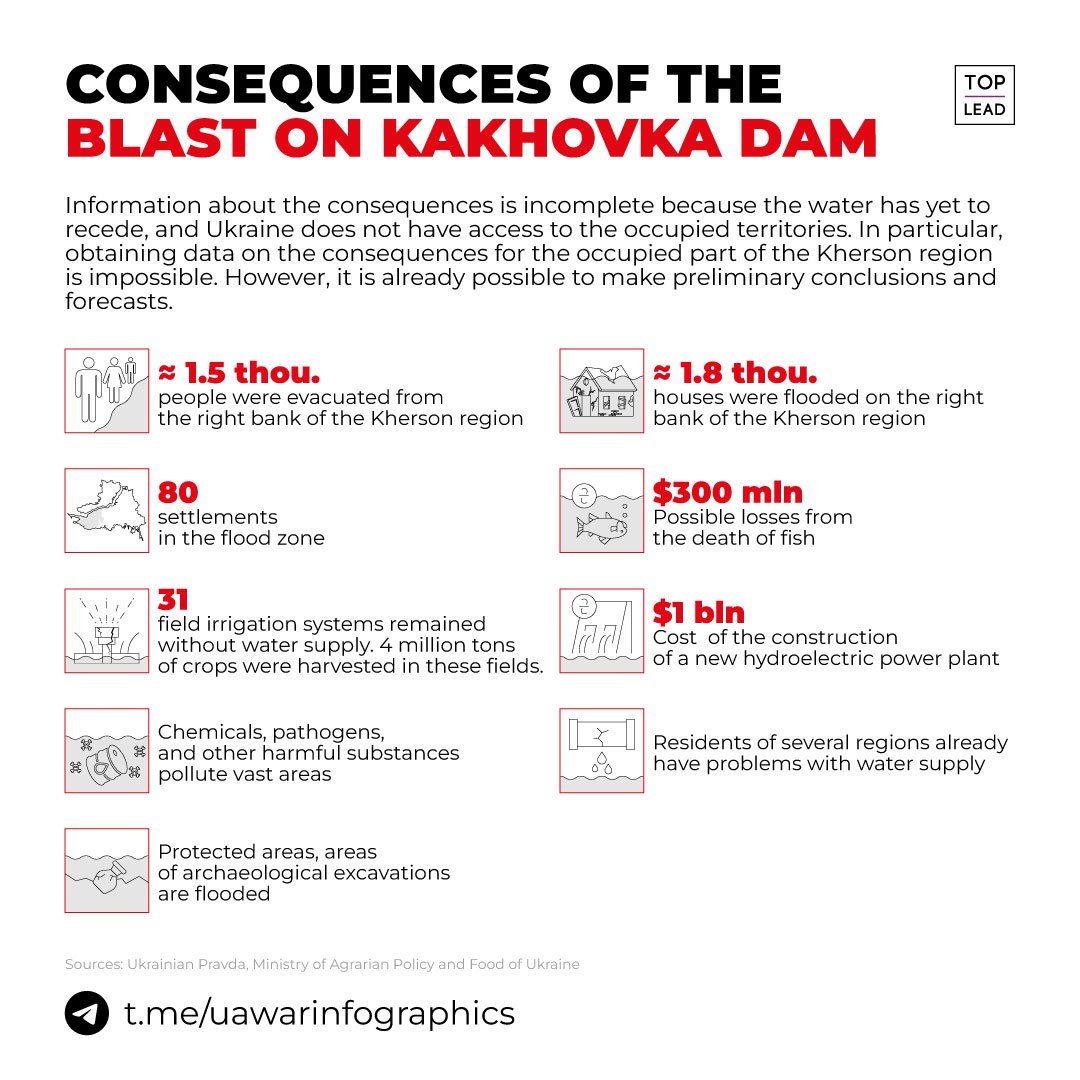

The scale of environmental destruction has prompted calls for new international legal frameworks. This disaster may become the first test case for prosecuting environmental war crimes under international law.

Truth Hounds and Project Expedite Justice researchers concluded that the case “may become the first application of the ICC’s Article 8(2)(b)(iv) of the Rome Statute, which concerns causing ‘excessive’ environmental damage compared to expected military advantage”.

Moreover, there is evidence that Russian troops prevented people from evacuation from the flooded areas, despite the deadly threat they unleashed to reach their ghost objective.

Much of the damage caused by the breach of Ukraine’s Kakhovka dam is irreversible, with likely changes to the environment that could have impacts on ecosystems and human health. The total damage is estimated at nearly $14 billion.