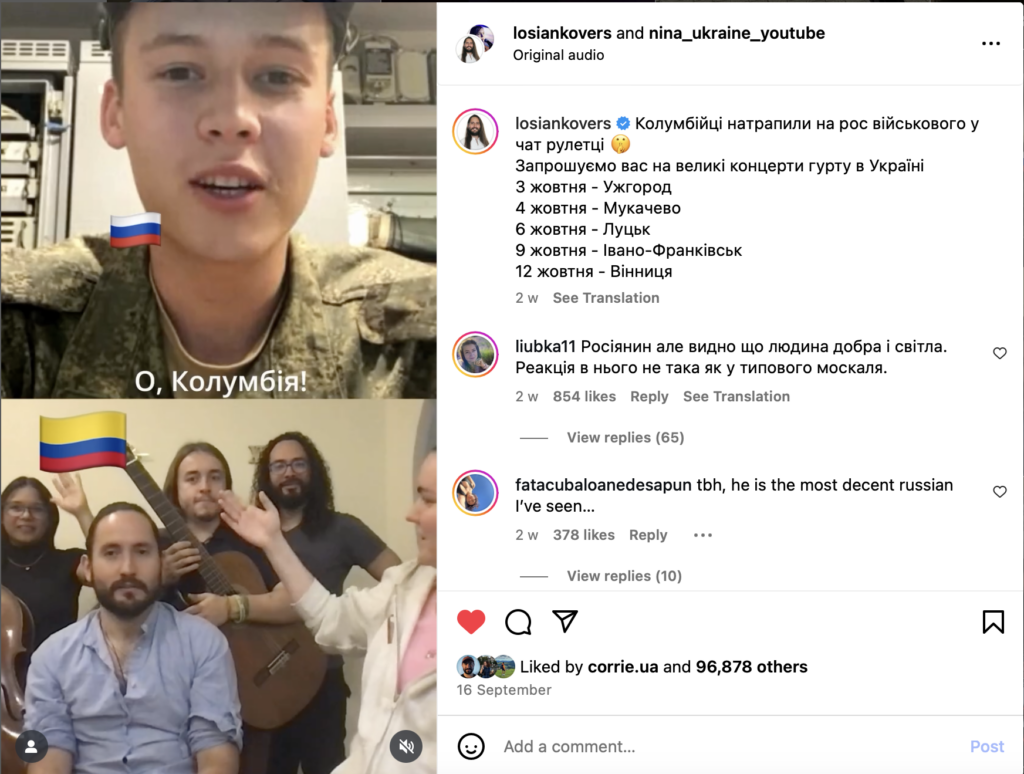

The Russian soldier wasn’t prepared for what video chat roulette would serve up.

Clad in a military uniform, looking too young to be in the army, he lights up when a group of Latin Americans with musical instruments appear on his screen. Finally, an interesting diversion. They ask him where he’s from.

“Russia,” the soldier replies. “And you?”

They tell him they’re from Colombia and Venezuela. “You play music?” he asks in broken English, miming a guitar. Obligingly, the band launches into a song.

The Russian’s palpable enthusiasm collapses quickly. The song is not just Ukrainian, it is one of the most controversial tunes in Ukraine’s repertoire: "Batko Nash Bandera" — Bandera, Our Father.

The song praises Stepan Bandera, a polarizing figure in Ukrainian history. While many Ukrainians view him as a hero who fought for independence, his legacy is controversial due to organizations under his leadership committing ethnic cleansing against Polish and Jewish civilians during World War II. Russians view the song as glorifying fascism, citing Bandera's wartime collaboration with Nazi Germany. Many Ukrainians, however, see him as a symbol of resistance against Soviet oppression.

The soldier's face falls, passing through shades of disappointment and disgust. But he doesn’t disconnect immediately. He waits, watching until the final notes fade, then exits the chat without a word.

This is how Los iankovers went viral.

Their videos capturing confused or angry reactions of Russians hearing foreigners sing Ukrainian songs have garnered millions of views and built a following of over 300,000 on Facebook alone.

They are currently touring Ukraine, performing in sold-out theaters and rehabilitation hospitals for soldiers, bringing what they call "music therapy" to a nation at war.

But Colombia's connection to Ukraine runs deeper than viral videos. Estimates of Colombian fighters in Ukraine vary widely, from several hundred to over 2,000, according to reports from soldiers and Ukrainian media, making them the largest Hispanic contingent in Ukraine's armed forces.

Growing up between two cultures

While most of the band members are Colombian, their vocalist, Ianko Bohdan, was born in Bogotá to a Ukrainian mother and Colombian father, inheriting both cultures.

His mother Natalia, a microbiologist from Kyiv, had moved to Colombia in the early 1990s. She met Ianko's father, Javier, at the music faculty of Colombia's National Pedagogical University—she studying piano, he studying violin. Music was woven into the family's DNA from the beginning.

"I identify as both," Ianko tells Euromaidan Press in an interview. "I don't have Ukrainian citizenship. I only have my Colombian passport. But I identify myself as 100% Colombian, 100% Ukrainian, not 50-50."

His parents sang traditional Ukrainian songs together at home. "My father doesn't speak Ukrainian, he has no idea of Ukrainian language, but he sings in Ukrainian because my mother taught him to sing in Ukrainian," Ianko says.

Folk songs like "Horila Sosna" ("Горіла Сосна"), "Chom Ty ne pryshov" ("Чом Ти не прийшов"), and "Yikhav Kozak za Dunai" ("Їхав Козак За Дунай") filled their household, creating a musical bridge between his Colombian life and his mother's Ukrainian heritage.

But it wasn't until 2014, when he was 19 years old, that Ianko felt a burning need to deepen that connection.

"I felt this very big need and wish to learn Ukrainian," he recalls.

Growing up, the family had spoken Russian, as so many Ukrainians do, as a result of centuries of Russian cultural dominance. After the Euromaidan Revolution Ukraine began reclaiming its linguistic identity. Ianko’s family followed suit.

"My mother also helped me because she has very good Ukrainian and now she even speaks Ukrainian," Ianko says. He learned quickly, driven by love.

"I think that the main thing that made it easier was my motivation. One of the most effective methods to learn any language is through music. So I learned songs and in parallel, I learned Ukrainian with the songs," Ianko says.

From university friends to Los iankovers band

Today, his bandmates are also learning Ukrainian. While it's more challenging for them, they're making progress.

"Even our violinists, our guitarists, they are able to answer some questions in interviews. They are able to speak a little bit in Ukrainian, and they didn't know any Slavic languages before," Ianko says proudly.

Despite their Ukrainian repertoire, the band's name is purely Spanish. It comes from a playful inside joke.

Years ago, when Ianko posted song covers on Facebook with his own unique style, a friend started calling them "Iankovers" combining his name with the word "covers."

When the group began performing on the streets of southern Colombia and Ecuador and people asked their band's name, someone spontaneously answered: "We are the Iankovers" and it stuck.

The core group formed at Colombia's National University, where Ianko studied music and met guitarist Nicolás, a mathematician with exceptional musical talent.

In 2022, Venezuelan violoncellist Isamar Fernández, who had fled Venezuela's political crisis and dictatorship, joined the band. Her experience under authoritarian rule gave her immediate empathy for Ukraine's fight against Russia's imperialist autocracy.

Most recently, in January 2025, Juan David, who plays flute and wind instruments, came aboard. Supporting them behind the scenes are two Ukrainian women: Nina, their manager, who orchestrates their social media strategy, and Tanya, who handles content creation.

Going worldwide through social media

Nina's arrival marked a turning point for the band. Three years ago, Los iankovers were playing small concerts in European pubs and cafés for Latin American communities living abroad, supplementing with street performances.

"We didn't have such a big audience. We had some viral videos, so some people had seen us even three years ago, but our social media weren't so strong," Ianko recalls.

Then came Nina, a former finance professor at the Ohio State University with a Ukrainian YouTube channel of 240,000 subscribers. After interviewing the band online, she traveled to Colombia and later Europe to create video content with them.

"I asked her to be our manager because I understood that we have the music, we have the product, we want to reach more people, especially in this hard time," Ianko says.

The decision proved transformative. "By the way, today we reached 300,000 subscribers on Facebook. Last year it was maybe 120,000 or something like that, so yes, we are growing," Ianko announces.

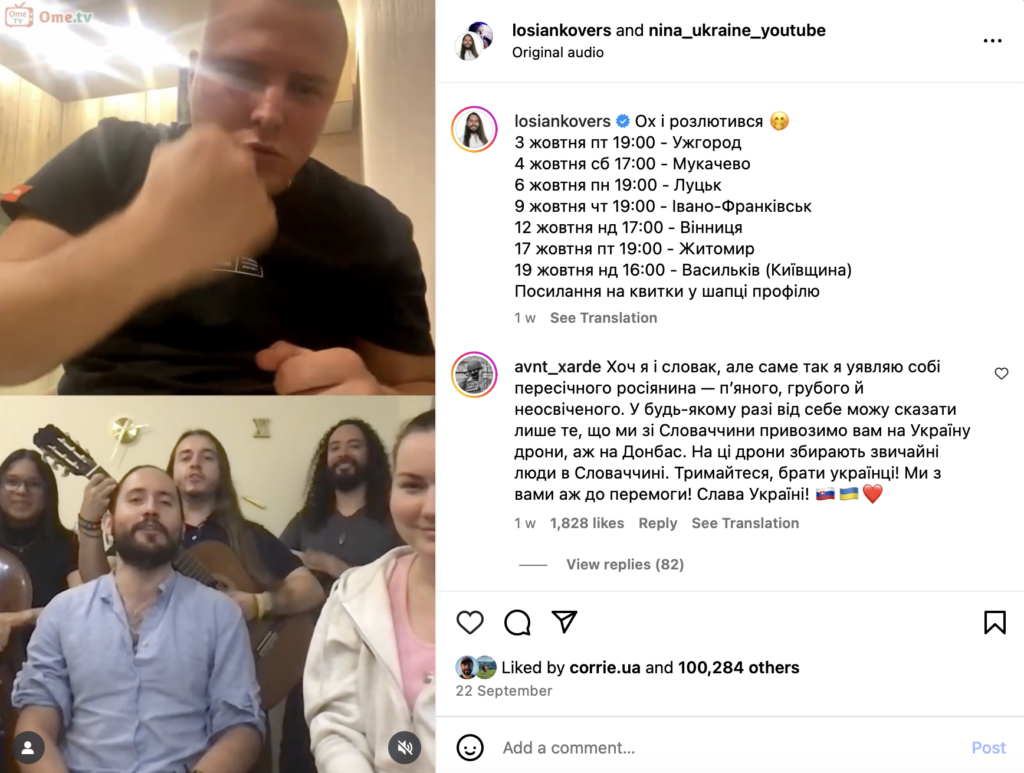

This explosive growth came from their most entertaining and highly-liked content: Chatroulette-style random video chat sessions with Russians. For Ianko, however, these videos are hard to create.

Los Iankovers are a Colombian band with a unique sound—blending traditional Ukrainian music with South American rhythms.

— Euromaidan Press (@EuromaidanPress) October 1, 2025

The group has gone viral online for their performances, and now they’re touring across Ukraine, bringing joy and hope to audiences in cities large and small.… pic.twitter.com/7nrgIyAfrq

"I am introverted," Ianko admits. "For me it's hard to do the chat roulette, especially with Russians. Of course I'm not glad to have contact with Russians. I don't like confrontations—this is not part of my comfort zone."

Still, he pushes past this discomfort because the impact is hard to deny. The band deliberately selects Russia in their country filter on video chat platforms, then performs Ukrainian patriotic and folk songs for unsuspecting Russian viewers.

Sometimes they select Ukraine instead, creating heartwarming moments with soldiers or diaspora Ukrainians. At other times they randomly choose countries like Greece or Macedonia.

Confronting Russians on camera to prove it's not just Putin

For Ianko, these videos serve a purpose beyond entertainment or viral fame.

"We get a lot of comments from soldiers in the front line, and they feel supported. They feel that they are not alone when they see how a Colombian band trolls Russians in order to support Ukraine."

Beyond boosting morale, the videos serve an educational purpose for foreigners who sometimes try to whitewash the Russians, instead showing viewers that Russian aggression stems from deep cultural attitudes, not just political leadership, not "just Putin's war."

"We want to show that it's a cultural problem. We want to show that it's not only Putin. The chaos is the consequence of this culture. Their politics are a consequence of the mentality of the people," Ianko says.

"Many Russians are guilty because they support the imperialism. They absolutely don't care about what they are violating in other countries," he adds.

For Ianko, the only path forward is clear, if difficult: "For us it's important to make people understand that the only way to solve this situation, sadly, is with force—with resistance.

He hopes Russia will undergo a process similar to post-World War II Germany—a fundamental rethinking of national identity and values that can only happen after military defeat.

Thousands of Colombians are also working toward that defeat—not with music, but with weapons.

Soldiers of Song: documentary on how Ukraine’s musicians battle Russian “cultural genocide” through music

Colombian fighters join Ukraine's battle against Russia

For Ianko, ensuring Ukrainians know about the Colombians fighting alongside them is crucial.

"For me, it's important to let Ukrainian people know that they are not alone, that a lot of people from my country Colombia decided to come here for different reasons," Ianko shares. "I even saw some interviews where Colombians say that after the war, they want to stay here because they found a new home."

Los Iankovers actively honor this connection by reserving free tickets for soldiers at every concert. In many cities, Colombian soldiers in rehabilitation attend their performances alongside Ukrainian soldiers, creating moments of solidarity between the two nations.

Many are former military personnel drawn by the opportunity to earn between $3,000 and $5,000 monthly—far more than they could make in Colombia—and the possibility of Ukrainian citizenship. They typically sign six-month contracts, much shorter than the three-year commitments of Ukrainian soldiers, yet receive the same pay.

These fighters bring valuable experience from Colombia's decades-long conflict against drug cartels and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

However, the technological warfare in Ukraine with its drones, artillery systems, and electronic warfare presents new challenges far beyond the improvised explosives they faced in Colombian jungles.

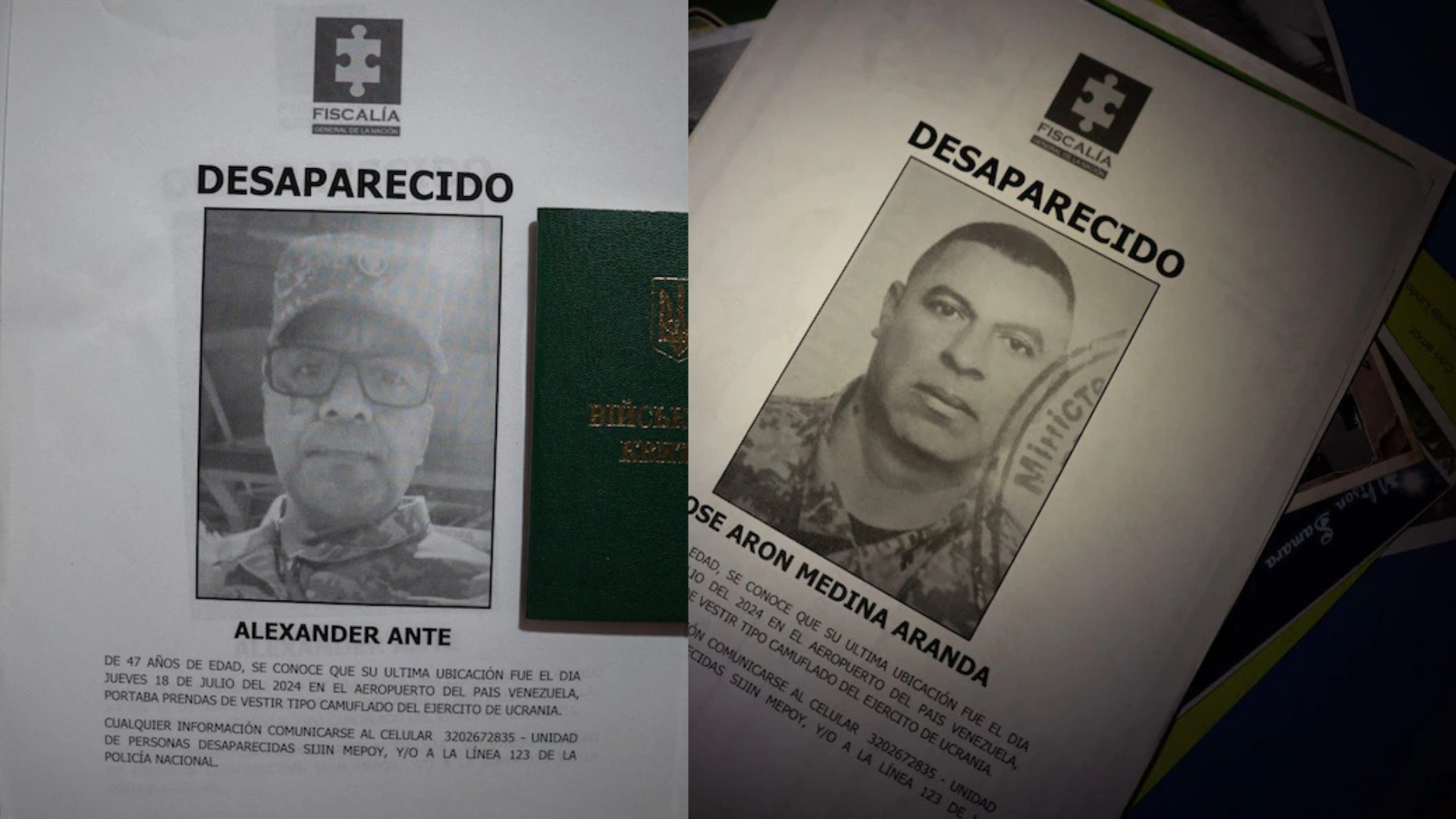

The situation became more complicated when two Colombian volunteers, Alexander Ante and José Aron Medina, were detained in Venezuela while trying to return home and subsequently sent to Russia, where they now face up to 15 years in prison on mercenary charges despite being integrated directly with Ukraine's Ministry of Defense.

The Telegraph: Colombian veterans who fought for Ukraine were kidnapped in Venezuela and handed over to Russia

From the Andes to the Carpathians

Asked about similarities between Colombian and Ukrainian cultures, Ianko becomes animated. "Absolutely. Even in the music elements, in the mountains culture, because we have the Andes and here are the Carpathian mountains."

The musical parallels are striking. The Ukrainian sopilka functions similarly to the Colombian quena; Ukrainian pan flutes mirror South American zampoñas or sikus (Andean panpipe).

"There are a lot of similarities between the pipes, and the interesting thing is that these instruments are also from the mountains," Ianko notes.

The traditional Ukrainian songs his parents sang to him as a child now get the Los Iankovers treatment—infused with Latin rhythms and played on instruments from both cultures. The mountain music of the Andes meets the mountain music of the Carpathians, and somehow, it works perfectly.

"We don't force this fusion—it's absolutely organic because we perform these songs and we just use some instruments that are close to us. Some Latin American instruments, we use some Latin American rhythms that fit very well with Ukrainian music," Ianko says.

But the connections go deeper than instruments. "I feel that Colombians, the same as Ukrainians, are very patient and emotional people, very warm people. The history of both countries is not easy."

He draws parallels between Colombia's long war against communist rebels financed by the Soviet Union and Cuba, and Ukraine's fight against Russian aggression.

Even the food and family values align. "The food is very organic. Also the family values—in Colombia as well as in Ukraine, the family is very important as the base of the society."

Talking about the differences, Ianko notes the contrast in communication styles: "There are a lot of protocols and filters in how we speak to each other at least in Bogotá. We are very careful not to get upset, so we speak very carefully. But the problem with that is that people hide a lot of emotions, negative emotions or even positive emotions."

In Ukraine, he finds something refreshingly different: "The communication is stronger, much stronger, but also more honest."

Perhaps most significantly, Ianko observes a difference in national identity:

"Here in Ukraine, people understand much more about their identity and this concept of nation. In Colombia, the concept of nation, patriotism, national identity is very confusing, quite different.

I think people here are much more patriotic and understand much more the value of their own land and their nation."

Building patriotism in Ukraine's future generation with music

This strong sense of Ukrainian national identity is something Ianko wants to nurture and preserve, especially in the youngest generation.

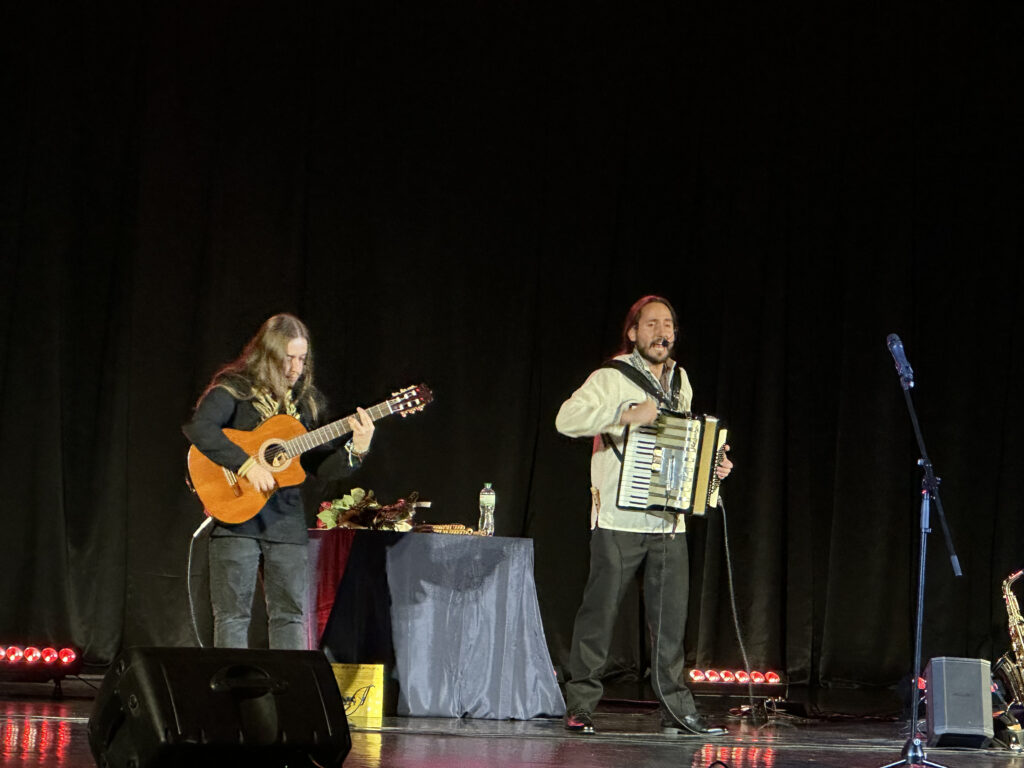

When Los Iankovers take the stage in Ukrainian cities, they're not just performing—they're providing what Ianko calls "therapy."

"To give hope and to give some joy in this hard time. When we see that people thank us, and even the soldiers do that, that is the biggest honor that we can get. We understand that we are giving some joy, some hope, and some support. That is kind of therapy," Ianko says.

The children at their concerts hold special significance for Ianko. Their concerts run an ambitious two and a half hours—a length that tests the limits of attention. Yet the children stay engaged.

"Usually there are a lot of kids in our concerts... but they keep the focus all the time of the concert, and they enjoy, and they come closer to the stage, and they dance," Ianko observes.

"They are the future of the nation, and we want to inspire them to love this music, to love this nation, the same as some musicians that I saw when I was a child inspired me to love this nation. So I want to do the same—to keep building this patriotism in this new generation," he says with conviction.

As Los iankovers continue their tour across Ukraine, performing for packed theaters, wounded soldiers, and dancing children, they embody a unique form of cultural resistance through the unexpected fusion of Colombian rhythms and Ukrainian melodies.

They troll Russians not for mere entertainment, but to demonstrate that Ukrainian culture is alive, vibrant, and worth defending while exposing how ordinary Russians perpetuate aggression through their imperialist attitudes and indifference to the suffering they cause.

Los iankovers perform in hospitals to offer hope and support the healing of wounded soldiers. They learn Ukrainian song by song, driven by their love for the music they perform each night.

That love is reciprocated. Ukrainian fans and a growing international following online feel deeply connected to the band's unique sound and mission.

After completing their current tour, Los iankovers plan to return to Colombia to showcase their Ukrainian repertoire there, continuing their mission of cultural bridge-building.

But before they leave Ukraine, there will be more video roulette sessions. Somewhere, a young Russian soldier will squint at his screen in confusion and anger. And somewhere else, a Ukrainian soldier recovering in a hospital bed will smile, knowing that even from across the ocean, someone is fighting for Ukraine's soul.

Los Iankovers are a Colombian band with a unique sound—blending traditional Ukrainian music with South American rhythms.

— Euromaidan Press (@EuromaidanPress) October 1, 2025

The group has gone viral online for their performances, and now they’re touring across Ukraine, bringing joy and hope to audiences in cities large and small.… pic.twitter.com/7nrgIyAfrq