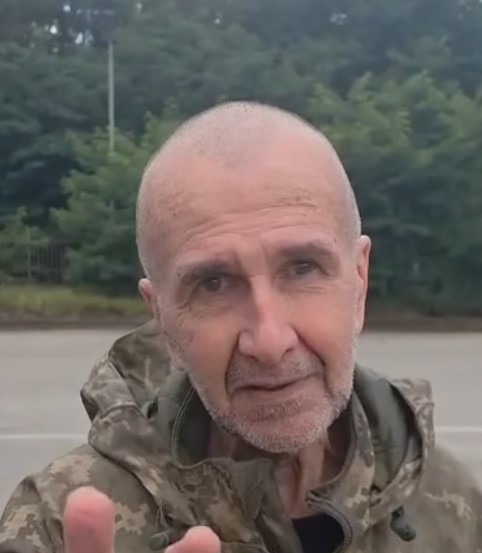

Since his release from a Russian prison, Ukrainian journalist Dmytro Khyliuk has barely been off the phone. BBC reports that he spent three and a half years in Russian captivity after being detained in the first days of the full-scale invasion. He was freed last month in a prisoner swap, one of eight civilians released in a rare move by Moscow.

Amid the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war, most exchanges between Russia and Ukraine have involved soldiers. The return of eight civilians, including Dmytro, came in a group of 146 Ukrainians. They did not disclose the exact terms of the deal, only that it included “people Russia was interested in.” One source told BBC that some of them were residents of Russia’s Kursk region, evacuated during Ukraine’s incursion in 2024.

Crowds gathered waving Ukrainian flags when the freed men returned, many of them emaciated from years behind bars. Stepping off the bus, Dmytro immediately phoned his mother to say he was finally free. His parents are elderly and unwell, and he had long feared never seeing them again.

A testimony of constant cruelty

Speaking to BBC after his release, Dmytro described brutal treatment in multiple Russian facilities.

“They grabbed us and literally dragged us to the prison and on the way they beat us with rubber batons shouting things like, ‘How many people have you killed?’” he recalled.

Guards sometimes set dogs on prisoners.

“The cruelty was really shocking and it was constant,” he said.

He was never charged with a crime. In the first year, he endured starvation, losing more than 20 kg in a few months. He lost more than 20kg in the first few months. He also saw soldiers tortured with electric shocks during interrogations. The sounds of their pain and the bruises on their bodies left lasting impressions.

Captivity begins at home

The ordeal started in 2022 in Kozarovychi, his family’s village near Kyiv. As he and his father Vasyl checked damage to their home during Russia’s assault on the capital, troops detained them. Both men were bound, blindfolded, and held in a basement under warehouses used as a Russian base.

Vasyl was released, but Dmytro was transferred deeper into Russia. His parents later received just two scraps of paper from him. One note read, “I’m alive, I’m well. Everything’s ok.” For months, they feared the worst.

Families left waiting

BBC reports that more than 16,000 Ukrainian civilians remain missing. Officials have confirmed that only a fraction are in Russian prisons. Moscow does not publish lists. In Dmytro’s area alone, 43 men remain unaccounted for.

One of them is Volodymyr Loburets, detained at the same time as Dmytro. He has a new grandson he has never met. His wife Vira told BBC,

“I had a husband – and now I don’t.”

Families are frustrated because the Ukrainian government will not swap Russian soldiers for civilian hostages.

Ukraine’s impossible choices

Ukraine’s human rights ombudsman Dmytro Lubinets told BBC that dealing with Russia is like “playing chess with an opponent who stands up, pulls on boxing gloves and punches you.” Ukraine has no Russian civilian prisoners to trade, while sending soldiers back in return for civilians would trigger more abductions. Only one previous exchange involved Ukrainians accused of collaboration. It is unclear if that approach will be repeated.

Kherson’s former mayor freed from Russian captivity on Independence Day, while current mayor still suffers behind bars

Home again, but changed forever

For Dmytro, the long wait is almost over. He is recovering in a Kyiv hospital before returning to his village. His mother Halyna can hardly mention his name without crying.

“When Dima called, he told me to be calm, that I shouldn’t cry anymore. But we haven’t seen our son for three and a half years!” she said.

33 Russian guards, medics, commanders: InformNapalm links POW abuse in Mordovia to named Russian staff

Back home, his house still bears shrapnel scars from Russia’s advance. He admits returning requires adjustment.

“So the trees are the same, the buildings are the same. But you understand this is a different country. You’re in a different reality,” he said.

Read also

-

Moscow cuts another lifeline to Europe’s human rights system as Putin moves to exit anti-torture convention

-

Kherson’s mayor who survives dog attacks and mock executions, reveals how he stayed loyal to his homeland in Russian captivity

-

Ukrainian POW returns from 7-year Russian imprisonment with his cat

-

Ukrainian journalist abducted from his garden in 2022 returns from Russian captivity weighing less than 45 kg

-

Russia opens “slave market” of stolen Ukrainian children — users can choose them by color of eyes