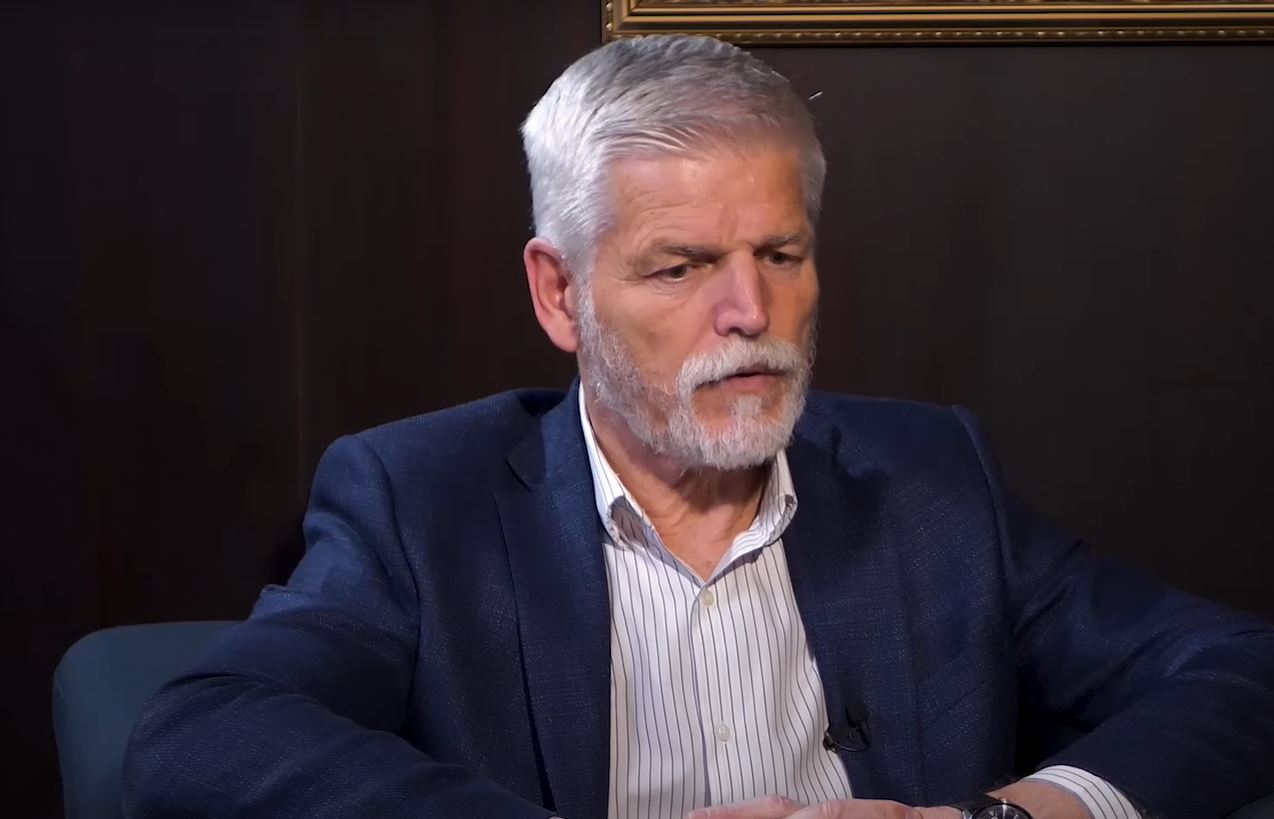

"Under Vladimir Putin, Russia has become a single-minded aggressor," Czech President Petr Pavel warned at Harvard last week.

His country, he explained, had "emptied its military house" to arm Ukraine, pioneering an ammunition initiative that delivered roughly 1.5 million large-caliber shells.

They're over.

Billionaire populist Andrej Babiš won Saturday's parliamentary election with 34.7%, declaring he will "review" the ammunition initiative and seek coalition with far-right SPD—whose leader wants to expel most of Ukraine's 380,000 refugees.

The shift represents more than just another European country moving right.

Czechia was Ukraine's per-capita champion, ranking in the top 10 globally for aid as percentage of GDP.

It launched Europe's most innovative ammunition procurement, sourcing shells from global markets when Western production couldn't keep up—and, in the words of Czechia's foreign minister, allowed to torpedo Russia's artillery advantage over Ukraine from 10:1 to 2:1.

Its loss would complete a Central European axis—Hungary, Slovakia, and now potentially Prague—systematically obstructing Ukraine aid.

But a total policy reversal isn't guaranteed. Analysis by Prague's Association for International Affairs (AMO) suggests EU and NATO membership won't be questioned.

What is expected:

- scaled-back Ukraine support

- potential suspension of the ammunition initiative

- review of 380,000 Ukrainian refugee permits

- and Prague joining Budapest and Bratislava in blocking EU consensus on Russia sanctions.

Czech ammunition initiative for Ukraine faces political opposition despite delivery success

Two futures hang on coalition math

With 34.7% of the vote (99% counted), Babiš's ANO won decisively—but the 69-75 projected seats still fall short of the 101 needed for majority, making his coalition choice the defining question.

- ANO—Babiš's centrist-populist movement built on technocratic efficiency and EU skepticism—at 34.7%.

- The center-right SPOLU coalition (Civic Democrats, Christian Democrats, and TOP 09), which has governed with STAN since 2021 and pioneered the ammunition initiative, trails at 23.2%.

- STAN, the liberal Mayors and Independents party, holds 11.2%.

- Pirates—a liberal digital rights party focused on transparency and tech policy—at 8.9%.

- The far-right, anti-immigration SPD (Freedom and Direct Democracy) stands at 7.8%. Its leader, Tokyo-born Tomio Okamura, wants to "expel most of 380,000 Ukrainian refugees" as a coalition condition.

- Motorists—right-wing newcomers campaigning against environmental regulations and EU climate policies—at 6.8%.

Babiš has already signaled his preference: "We will definitely lead talks with the SPD and the Motorists."

The immediate aftermath

Outgoing Prime Minister Petr Fiala conceded Saturday evening: "I congratulate the election winner, which is Andrej Babis."

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán was faster, congratulating Babiš on X: "Truth has prevailed! A big step for the Czech Republic, good news for Europe."

On Ukraine, Babiš carefully threaded a needle—promising to "review" the ammunition initiative while insisting "we are clearly pro-European and pro-NATO." He said the government would "discuss it with President Zelensky if necessary."

President Pavel will begin coalition talks with elected party leaders Sunday.

The former NATO general holds constitutional power to reject ministers who "support the country's exit from the EU or NATO"—leverage that could force Babiš away from SPD partnership despite his stated preference.

Other institutional constraints exist beyond the presidency.

- The Senate—where the opposition holds majority—could obstruct government initiatives.

- The position of national security advisor, if retained, might serve as another balancing actor with bureaucratic experience close to the prime minister.

And Babiš himself may resist his coalition partners' demands.

"I don't think his wish is to govern with crazy people or way too crazy people," Pavlína Janebová, AMO's research director, said during the GLOBSEC forum in Prague.

His pragmatism—or cynicism—may ultimately prove a moderating force.

In June 2025, Pavel declared he would "refuse to accept the appointment of ministers who support the country's exit from the EU or NATO," applying this specifically to Stačilo! and SPD nominees for security and foreign policy posts.

Russian warplanes fly into NATO airspace — Czech President says maybe it’s time to shoot them down

The pragmatic populist puzzle

Understanding Babiš requires looking past the "Czech Trump" label. "Babiš has a reputation as sufficiently pragmatic (or cynical) to downplay his Ukraine-skeptic and NATO-skeptic views in the interest of taking power again," notes former US Ambassador Daniel Fried.

The 71-year-old billionaire—worth $4.4 billion from his Agrofert conglomerate—governed as prime minister from 2017 to 2021 without dramatically shifting foreign policy. His current anti-Ukraine rhetoric may be electoral positioning, constrained by business interests more valuable than Moscow or Beijing can offer.

His dependence on EU funds creates additional leverage.

"For Babiš, it is very important to keep the flow of European funds and to have this support for the Czech economy and also his businesses here in place," Vít Dostál of Prague's AMO think tank noted at the GLOBSEC forum, suggesting Brussels could use conditionality mechanisms as negotiating tools.

"ANO, led by Babiš, have insisted that accepting the country's continued membership in the EU and NATO is the 'red line' in their talks with potential coalition partners," reports Warsaw's OSW Centre for Eastern Studies.

"This is a signal to prospective allies, namely SPD, which has called for a referendum on EU membership."

How the unthinkable became thinkable

The transformation from 80% public engagement with Ukraine in February 2022 to 51% opposing military aid in February 2025 stems from genuine grievances amplified by sophisticated exploitation.

Czech households lost an average of 3.5% of disposable income from energy inflation between February 2022 and February 2023, with gas prices rising 110% and electricity 95%. Pensioners lost 5.7% of their income, single parents 4.6%.

With 97% dependence on Russian gas in early 2022, Czech Republic ranked fifth highest in Europe for energy inflation impact.

Inflation peaked at 17-18%—the highest since December 1993. Real wages didn't recover to 2019 levels until 2024, leaving a multi-year period of declining living standards that became the campaign's dominant issue.

More striking than war fatigue is the security perception reversal: polling in September 2025 found only 25% of Czechs believe supporting Ukraine makes their country safer, while nearly 50% believe the opposite.

Support for "quick end to conflict even at cost of territorial concessions" reached 72% by early 2025.

Russian disinformation amplified these grievances.

- Czech intelligence busted the Voice of Europe network in March 2024—a Moscow-financed Prague-based propaganda operation paying European politicians to discourage Ukraine aid.

- Researchers uncovered ~300 anonymous TikTok accounts with cumulative reach of 5-9 million views per week, exceeding the combined official accounts of all major party leaders.

Babiš exploited perception gaps expertly. Czech contribution to the ammunition initiative represents less than 2% of total funding—other nations paid, but Czech diplomacy orchestrated procurement. Yet Babiš successfully transformed it from foreign policy achievement into domestic economic liability with his "rotten and overpriced" criticism.

The new European divide

The Czech shift fits a broader pattern transforming European politics.

"What we have is a cleavage between status quo, mainstream liberals and illiberal disruptors," explained regional expert Daniel Hegedüs at a panel discussion during the GLOBSEC forum in Prague.

"That killed the existing elite consensus about foreign and security policy strategic issues, even in those countries where it was the fiercest in Europe."

Babiš's victory could complete a Central European axis with Hungary and Slovakia, who systematically obstruct Ukraine aid and block EU consensus on Russia sanctions.

This spit has also fractured the Visegrad Group, an alliance of Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and Czechia in 1991 for NATO/EU accession coordination, according to AMO analysis.

Because of it, Poland and Czechia have prioritized other formats like the Weimar Triangle and Bucharest Nine, forming a Prague-Warsaw axis against Budapest and Bratislava.

Will Czechia now join Hungary and Slovakia's camp?

Not necessarily. Babiš faces institutional constraints Orbán and Fico don't: a president who can veto ministers, an opposition-controlled Senate, and business dependence on EU funds Brussels could threaten.

What comes next

Babiš's victory confirms Europe's ammunition architect will become a country undermining EU consensus on Ukraine—the only question is how far.

His stated preference for coalition with SPD and Motorists would end government activities to arm Ukraine, suspend the ammunition initiative, review residence permits for 380,000 Ukrainian refugees, and complete the Central European axis opposing Western policy.

But his careful language—"review" rather than "cancel," pledging to "discuss with Zelensky," insisting on "pro-European and pro-NATO" stance—suggests awareness of constraints.

The ammunition initiative has funding secured through 2026, with plans to deliver 1.8 million shells by the end of 2025. Whether Babiš can actually suspend it depends on coalition arithmetic, presidential vetoes, and business interests that may prove more valuable than campaign promises.

What's certain: The gap between what Babiš promised voters and what structural factors allow him to deliver will determine Ukraine's actual losses from Prague's political earthquake.

This article was updated after election results came in