WASHINGTON—In the parking lot of the Smithsonian’s smallest museum, 18 of 29 spots were full. But inside, there were no couples on first dates or hordes of tourists milling about the exhibits.

In fact, there were no visitors there at all. Just 18 employees waiting for something to do.

On a sunny, late-summer day, this reporter stood outside the museum — located in a Washington, D.C., slum, far from any tourists — from noon to 3:00 p.m., ready to count visitors. But there was no one to count. At 12:28 p.m., one woman entered while screaming into her cell phone, “You ain’t sh*t.” She stayed for just long enough to use the bathroom, and left lecturing whoever was on the other end of her call about his or her “motherf***ing ghetto ass.”

Welcome to the Anacostia Community Museum, a six-room exhibit hall that receives $3 million each year in federal funding. The museum opened in 1967 to focus on “African American history, community issues, local history, and the arts.” Since then, the Smithsonian has added two separate, much larger museums focused on African art and African American history, making it largely redundant. Yet it remains, as if someone simply forgot to close it down.

Now, the government is finally weighing whether to do just that. Ten years after the massive African American History and Culture Museum supplanted it, there’s little reason for the Anacostia Community Museum to spend millions to welcome a handful of visitors a day. The Trump administration’s 2026 budget proposes zeroing out funding for the Anacostia Museum, saying its exhibits should be moved to the larger one. Congress is yet to act on that proposal.

But it may soon. Smithsonian museums have enough funding to remain open through October 6. But as the government shutdown continues — and the Trump administration leverages the funding freeze to slash nonessential programs and personnel — this little museum could soon find its taxpayer-funded endowment on the chopping block.

A Day At The Museum

At 1:39 p.m., a van pulled up with the only other attendees that showed up during this reporter’s three-hour stakeout. The visitors were there only partly of their own volition: four elderly residents from a nursing home in the wealthy section of D.C. were carted in by three nursing home staff. They ended their field trip at 2:30 p.m.

When this reporter finally entered, 10 employees were standing in the lobby, staring at the front door. They greeted me enthusiastically and offered me a Starbucks coffee from a fancy kiosk — an amenity that primarily serves employees, since coffee isn’t allowed in the main section. In a break room adorned with a big-screen TV and mahogany furniture, four black female employees and one white, green-haired employee of uncertain gender relaxed.

Get 40% off new DailyWire+ annual memberships with code FALL40 at checkout!

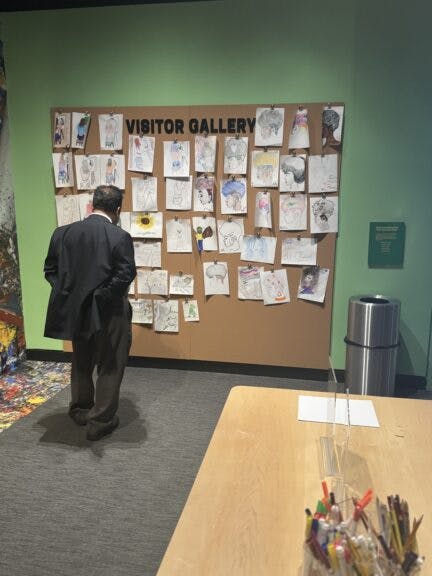

Even with the paltry amount of space to fill, the slogan out front, “Powered by the People,” isn’t just a nod to communism; it’s an acknowledgment that a large portion of the content is simply coloring book pages scribbled on by visitors that have been affixed to the walls. It’s as much of a museum gallery as the grocery store community bulletin board.

In one of these “Visitor Galleries,” guests take a printed-out piece of paper containing the silhouette of a head with an Afro, color in the hair using provided crayons, and pin it to a large bulletin board. Some added messages on them, such as “Gay Rights Matter.” Another wall is dedicated to pages that visitors colored in using stencils of musical instruments.

With no visitors to attend to, a Smithsonian employee peruses the art.

Nearly half of the museum, including a section named “A Century of Black Arts Education in Washington, DC,” is dedicated to knick-knacks pertaining to local high schools, memorabilia that might be better suited in the schools themselves rather than a national museum. According to a plaque: “It would be difficult to name a high school, the graduates or former pupils of which have achieved success in such numbers and of such brilliancy as have those trained in [Dunbar] High School.”

(According to D.C.’s most recent standardized test scores, only 1% of Dunbar students are proficient in math.)

One section is dedicated to children’s posters promoting government spending and political activism. There are posters celebrating teachers’ unions, demanding increased pay for teachers that state, “No funds, no arts, no future.” One poster implores D.C.’s high school students to skip school — something Dunbar’s students might not need much persuading to do — for a “walkout” to “show the D.C. city council” that “funding matters!!!”

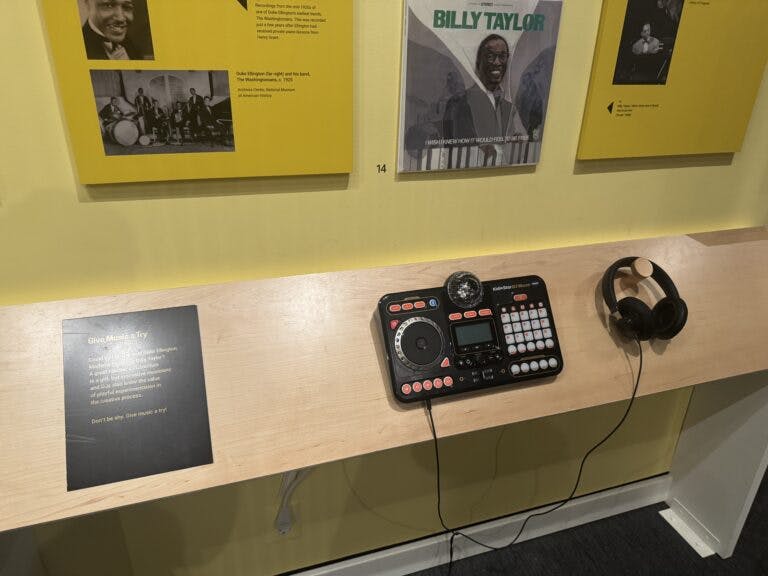

A section dedicated to jazz consists of TVs playing videos, one of which inaccurately claims that the drum was invented in Africa. An exhibit invites visitors to “Give Music a Try” using a DJ machine that allows them to make wicka-wicka record-scratch noises. It wasn’t plugged in.

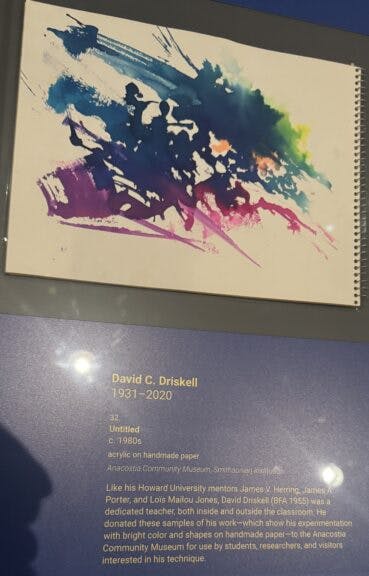

The museum contains only a few pieces of artwork, all of which look like they were made by small children, or were an accident involving spilled paint that the 18 staffers had not gotten around to cleaning up.

One room is dedicated to photography, which seems like a dump of someone’s iPhone gallery. A photo features a D.C. high school marching band from 2018, while another simply depicts people in the museum itself, looking at one of its exhibits. It’s as if someone wanted to create content for the museum without having to leave it, or wanted proof that, at one time, someone actually visited.

Information board exhibits outside continue the struggle to fill space, like a student padding out an essay to meet the teacher’s three-page requirement. One explains how the purpose of the museum is to “answer critical questions, such as: Where do we come from? Who are we as a people?” It seems to run out of ideas before answering, shifting to a picture of an oak leaf and noting that more than 500 species of caterpillars live in oak trees.

Another sign tells residents that there is a river nearby, and says the museum highlights the Anacostia watershed “through the lenses of faith [and] race.”

‘Collective work to build a more equitable future’

Most facilities whose budget is difficult to justify based on purely practical considerations might avoid personally antagonizing their funders. But the Anacostia Community Museum is nakedly partisan, thumbing its nose at the administration that will determine whether it has a future.

The museum’s website, for example, invites visitors “to join us in our collective work to build a more equitable future for all.” It calls for “reckoning with our racial past,” and “environmental justice.” An exhibit touts “the rise of Black Power.”

That’s despite the fact that in March, President Donald Trump signed an executive order calling to remove “improper ideology” from the Smithsonian. Vice President JD Vance is on the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents, which is helmed by Chief Justice John Roberts. The order barred exhibits that “divide Americans based on race” or that cast the United States as “inherently racist, sexist, oppressive.”

Some Smithsonian officials have resisted, saying it is an independent institution, even though 70% of its funding comes from the federal government. This month, the institution was required to turn over information about its content to the White House.

One of the Anacostia museum’s exhibits, called “We Shall Not Be Moved,” illustrates the fatalism that the Trump executive order seeks to remove from the museums, which serve as the front door of America for visitors, foreign and domestic.

The exhibit is about a crime-ridden subsidized housing complex in Southeast D.C. that was torn down in 2019. The government replaced the rundown housing projects with a development that is home to people of all incomes and races, yet the museum says this is “just one example of a historical African American community” engaging in “struggle across the U.S.” It shows visitors a map of majority-black areas across the country and asks a leading question to which only one answer is acceptable: “Why do you think they were targeted?”

The museum complains that the housing project was a place of “oppression and depression,” yet somehow simultaneously laments that it was later “destroyed.” That sort of clinically depressed, all-roads-lead-to-racism cynicism and shortsightedness mirrors how the museum may finally meet its own end.

‘A ghetto operation as it were.’

The Smithsonian exists to run museums of national importance, not neighborhood bulletin boards. The Anacostia outpost was justified as a marker of black culture, a half-measure towards advocates’ ultimate goal of a larger African American museum on the National Mall. In 1989, the Anacostia museum’s then-director, John Kinard, said just that, casting doubt that we’d ever see the larger museum.

“It was convenient to start something off in a ghetto,” Kinard said. “A ghetto operation, as it were. But a ghetto operation for 20 long years?” He called then-Smithsonian Secretary Robert Adams a “closet racist” who “would never agree to an African American museum on the Mall.”

But in 2016, Kinard got his way. The massive African American History and Culture Museum opened on the National Mall. Now, the people who complained about the lack of that museum also complain about the predictable result of its opening: the smaller museum’s likely shuttering.

African American History and Culture Museum / Smithsonian

Congress’s Committee on House Administration, which oversees the Smithsonian, didn’t return a request for comment.

According to the Smithsonian’s official statistics, in 2019, after the larger museum was in full swing, the Anacostia museum saw only 8,034 visitors, or five per day. In 2021, the figure was still five per day (COVID affected the attendance of all museums that year, but the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum nonetheless saw 420,000 visitors).

For 2024, the official statistics claimed 14,076, or about 38 a day. But, its website includes the caveat, “the counts sometimes include staff.” Its federal budget provides 17 full-time employees (the 18th employee we identified was a Metropolitan Police officer). The Daily Wire’s experience suggests that the official numbers are either inflated or count all employees. Even counting the bathroom user and the nursing home aides, the number I saw over three hours would work out to 18 over the seven hours the museum is open.

In the end, the museum seems to exist as a multi-million dollar jobs program and not much else — and its oversized staff may have actually obscured the fact that there is little demand for its offerings. But visitors may learn at least one thing, thanks to the fact that it has persisted for nearly a decade even after it was replaced by a larger museum: There is no such thing as a temporary government program.