Where controversial topics like religion are concerned, unanimity is not what one expects from the Supreme Court. But unanimity is exactly what the court managed in Catholic Charities v. Wisconsin, where it held that the state improperly denied Catholic Charities a religious tax exemption. There, all nine justices hung together by keeping their decision narrow, correcting Wisconsin only to the extent that the state’s criteria for religiosity discriminated between religions.

That uncontroversial approach allowed the court to avoid tougher, recurrent issues arising from the fact that while churches exist apart from the state, many of their subsidiary entities are incorporated under state law—meaning states like Wisconsin could render many aspects of church life subject to state control.

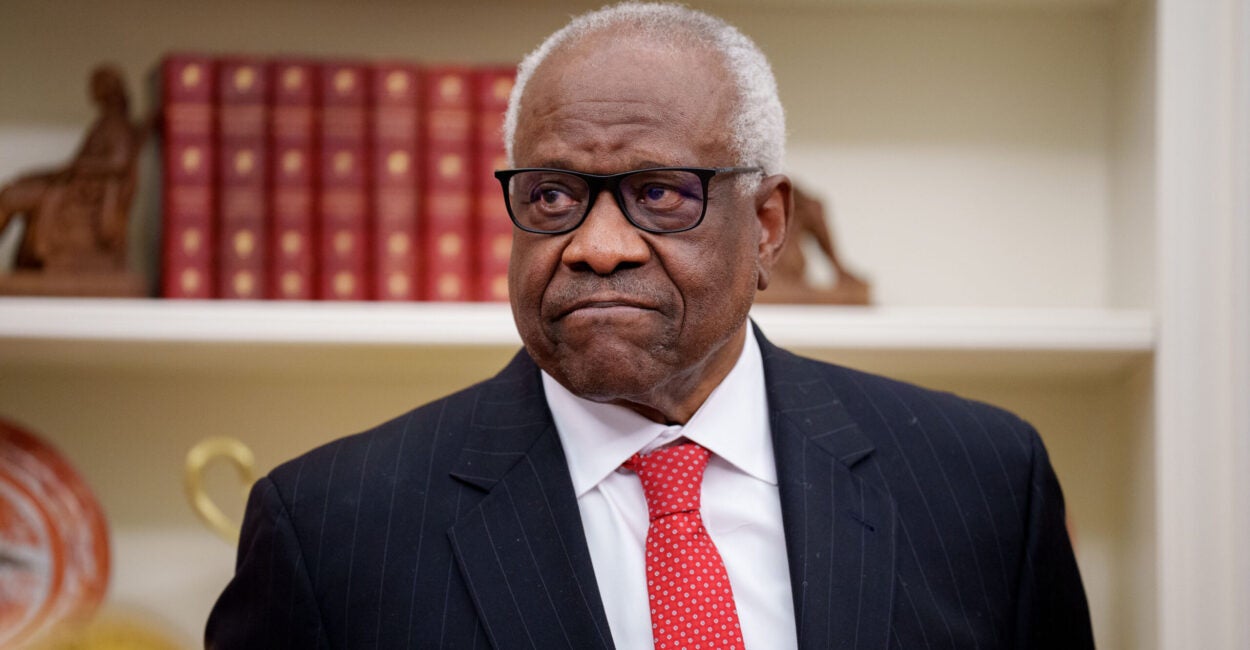

Justice Clarence Thomas did not miss the opportunity to comment on that problem.

In his solo concurrence, he declared that while religious institutions possess a “dual personality,” ultimately, “the corporation is made for the church, not the church for the corporation.” In so saying, he outlined a doctrine of governmental deference to the claims of religious authorities on what organizations comprise their religious body.

The court’s unanimous, narrow holding was that the Wisconsin Labor Commission unconstitutionally discriminated among religions when it denied Catholic Charities religious (tax-exempt) status because it did not actively proselytize while engaging in charitable works. Thomas agreed with that, but chose to confront a related question: is it up to a state to determine whether a church organization is “religious” in the first place?

Wisconsin relied on the charity’s legal charter of incorporation to establish the charity’s separation from the Roman Catholic Church and, thus, its supposed secularity. But Thomas rejected that move, saying that embedded in the First Amendment is the “Church Autonomy Doctrine”: the idea that church and state are separate and equal sovereigns within their respective spheres. Just as a church should not interfere in the operations of the government, so the government should refrain from interfering in the operations of churches.

Thomas grounded this in precedent, citing the 1952 Supreme Court case Kedroff v. Saint Nicholas Cathedral, which held that churches have the right to “decide for themselves, free from state interference, matters of church government as well as those of faith and doctrine.”

The effect of that doctrine is that while churches form corporations to handle their practical affairs, the government cannot then treat those corporations as the church itself. To do so would be to render the church subsidiary to the state because a corporation “is a mere creature of law” that “possesses only those properties which the charter of creation confers upon it” (Dartmouth v. Woodward). Thus, civil authorities may not reduce churches to their legal structures, pretending that its various corporate embodiments constitute the true religious body.

Justice Thomas’s conceptualization of churches has an unlikely but illuminating historical analogue: European monarchies.

In his work “The King’s Two Bodies,” historian Ernst Kantorowicz examined medieval kingship and determined that the king was imagined as having two bodies: the body natural and the body politic. The body natural was the king’s physical person, encompassing his personal habits, predilections, relations, and beliefs.

In contrast, the king’s body politic was the eternal office of the sovereign invested in the king. It was the body politic which performed the duties of state, received foreign emissaries, and governed the people.

The immortal office of the body politic manifested itself in the king’s mortal body natural. When the body natural perished, the body politic simply migrated to the next regent: “The King is dead, long live the King.”

Thomas’s description of religious corporations as having a “dual personality” suggests a natural parallel between his view of church autonomy and Kantorowicz’s work.

What are the church’s two bodies?

First and foremost is the body eternal of the church, its flock of believers and internal structure, which is prior to any legal classification. In contrast, the body legal of the church is its corporate status: how the law alone views the church. The body eternal of the church is everlasting and immutable, while the body legal constantly changes with the law.

Under this view, while the body eternal might manifest in a body legal so that it can “manage [its] temporal affairs,” the body eternal is always preeminent. The body eternal is the one protected by the church autonomy doctrine. And though the government may regulate some aspects of the church’s body legal (the body legal is, after all, a creation of the government), it must respect the body eternal as a separate and sovereign authority.

When Wisconsin determined that Catholic Charities was separate from the Catholic Diocese of Superior and therefore not religious, the state ignored protests from the Bishop of Superior that, though the organizations might exist under different legal designations, Catholic Charities was really a branch of the Catholic church. Yet Wisconsin relied on the authority of Catholic Charities’ state-granted charter of incorporation rather than the Bishop’s judgement, and, by doing so, tried to ignore or subordinate the Catholic church’s body eternal.

The two-bodies framework applies readily to the Catholic Charities case, but applying it in other cases might be trickier. The legal code is packed with instances in which civil authority defines or regulates the corporations that religions use for their temporal work.

Consider just one area: that of taxes. The tax code attempts to regulate which organizations can and cannot be officially part of a church (and thus receive religious tax breaks).

Take an example that D.C. natives might recognize: the gift shops in the basement of the National Basilica of the Immaculate Conception. Those shops sell religious jewelry, icons, and books. Are they legally a part of the church?

Currently, the IRS approaches businesses like these by examining whether they engage in “a business activity not substantially related to [the church’s] tax-exempt purpose.” But this requires the IRS to engage in a decision about what the “purpose” of a church is—meaning it might trench on religious authorities’ judgments.

Thomas would seem to resolve that problem by “asking the church.”

How far does this deference extend?

Right now, the IRS uses a 14-factor test to determine whether a body can be recognized as a church. Relevant factors include the existence of a creed and form of worship, a definite and distinct ecclesiastical government, and an established place of worship with regular congregations.

But Wisconsin also had religious criteria for its tax exemption, albeit far fewer than the IRS. Would Thomas then interpret the IRS criteria as interference by civil authority in the body eternal of a church?

While Thomas’s approach might create new knots, it might also untangle others.

It seems certain that this would allow a broader array of ministerial and charitable entities to claim the favorable tax treatment of the parent church. Their inseparability from the parent church could redound to their benefit in other ways too, potentially strengthening free exercise claims these entities might make against secular regulations that conflict with their religious commitments.

Thomas’s conception of the church autonomy doctrine raises questions, but it also affords the hope of greater leeway for religious organizations seeking to perform good works. Though it might be unlikely that rest of the court sees these matters Thomas’s way, his doctrine offers litigants a robust line of argument that could still inform the court’s future liberty cases.