Faith and sports go hand in hand. Quarterbacks quote Bible verses in interviews, and today’s top NBA players, from Golden State Warrior standout Stephen Curry (verses of scripture adorn his sneakers) to Indiana Pacer sensation Tyrese Halliburton (he cites church as “a big part of my success and my sanity”), count themselves as two of the 62% of Americans who call ourselves Christians.

As sports fans nationwide watch the drama of the 79thth NBA Finals unfold, it’s worth telling the story of basketball’s Christian roots. Indeed, Christianity was the driving force behind the game’s origin story.

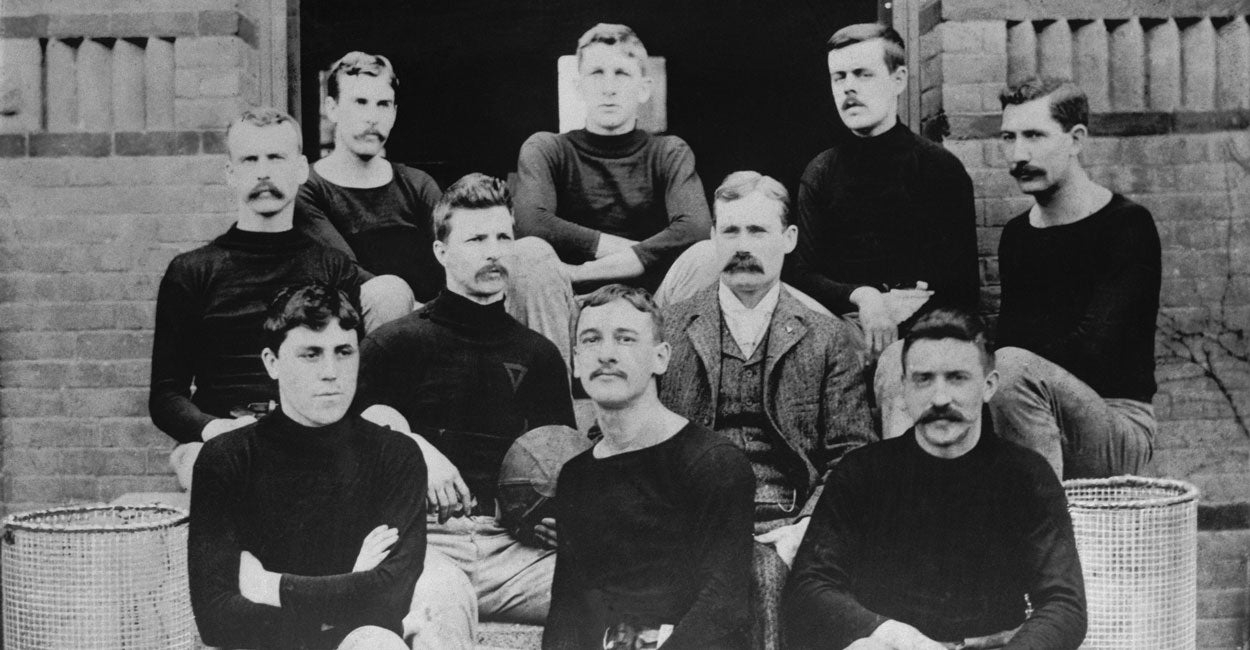

“I want to take you back to the first game of basketball in Springfield, Massachusetts in 1891,” Paul Putz, author of “The Spirit of the Game: American Christianity and Big-Time Sports,” told Our American Stories. “Eighteen grown men, most in their mid-twenties—walked into the gym at the International Young Men’s Christian Association Training School, where they were students. There were two peach baskets tacked to banisters on opposite sides of the gym, ten feet off the ground. There was a soccer ball too, and thirteen rules for a new game their instructor, James Naismith, explained to them.”

Putz described that first game. “They divided into two teams of nine: No dribbling, no jump shots, no dunking. Instead, they passed the soccer ball back and forth, trying to keep it away from their opponents while angling for a chance to throw it into the basket.”

There was no template for what a shot might look like, Putz explained. As the players positioned the ball at the top of their heads to toss it toward the basket, a defender would swoop in and grab it away. “If you’ve ever tried to coach second graders, it was probably a scene like that—except with big players and beards,” Putz said. When the game ended, just one person made a shot. The final score: 1 to 0.

To the students—and Naismith—it was a success. The students loved the challenge and possibilities of the game. Naismith loved those things, too. But he loved what the game represented, and why he was at the YMCA Training School in the first place.

On his application, he was asked to describe the role for which he was training, and wrote: “To win men for the Master through the gym.” Naismith’s idea was simple, but revolutionary: He believed sports could shape Christian character in ways mere study could not.

So who was this man who created one of America’s great homegrown sports? “He grew up in rural Canada,” Putz noted. “His parents died of illness when he was nine, and his uncle, a deeply religious man, took him in. When Naismith was fifteen, he dropped out of school, working as a lumberjack, but returned to high school at the age of twenty and entered college with the goal of becoming a minister.”

Most Christians in Naismith’s day viewed sports as, at best, a distraction: others saw sports as a tool of the devil. “But Naismith was coming of age during the rise of a new movement called ‘Muscular Christianity,’” Putz said. “It pushed back against the dualism that separated the spiritual and physical,” Putz explained. “The body itself had sacred value, they believed, and human beings should be understood holistically—mind, body, and soul intertwined.”

For Naismith, this idea came home in an epiphany playing football as a seminary student. During a game, a teammate lost his temper and let out a stream of curse words. During a break, he turned to Naismith and said sheepishly, “I beg your pardon—I forgot you were there.”

Naismith never spoke out against profanity, but his teammate felt compelled to apologize because—in Naismith’s words—“I played the game with all my might, yet held myself under control.” His teammate was responding to Naismith’s character on and off the field.

Soon after that encounter, Naismith heard about the YMCA Training School in Springfield, a new college dedicated to connecting physical activity and Christian formation. And away he went to America to invent the game we know and love.

“Naismith believed strongly in individual expression, and wanted basketball players to have space to create,” Putz explained. “He celebrated inventive moves—like the dribble and the hook shot—and expressed awe as players pushed the limits of what was possible.”

But Naismith also understood that with freedom came constraints. “Basketball is personal combat without personal contact,” Naismith would often say. Players can move anywhere at any time, and get close to their opponents, but can’t overpower them physically, Putz explained. The only way to make the game work is by consistently applying the rules. Which is why Naismith’s favorite role wasn’t player or coach but referee.

Naismith would become a pioneer on more than one front. In the 1930s, while a professor at the University of Kansas, a young African American student named John McLendon enrolled,” Putz explained. “He wanted to join the basketball team—but Kansas didn’t allow Black players.” Naismith took the young man under his wing, and McLendon would later become one of the most important basketball coaches of the 20th century.

Basketball was influenced by Americans of all stripes. “In 1892, Senda Berenson, a Jewish instructor at a women’s college, saw basketball as a rare opportunity for women to participate in sports,” Putz said. “She adapted the rules and helped make it the most important women’s team sport of the 20th century.”

The Jewish community embraced the game early, producing many of its first stars and innovators. So did Catholics and Latter-day Saints. Basketball also crossed racial and ethnic lines. Though the YMCA was segregated, Black Americans created their own spaces—often through churches—and built thriving basketball cultures, especially in cities like New York and Washington, D.C.

It didn’t take long for Naismith’s creation to became a pluralistic and collaborative force—a gift to the world, developed and shaped by many hands, Putz added.

“One of my favorite Naismith stories comes from the 1920s,” Putz concluded. “He dropped by a small college gym in Iowa, and a pickup game was about to begin. The players needed a referee and spotted the old man in the bleachers. One ran over to ask if he’d officiate—but before Naismith could respond, another player interrupted: ‘That old man? He doesn’t know anything about basketball.’ The players walked off to find someone else. Naismith just smiled.”

The fact is basketball would not be the game we know and love today if it hadn’t been for Naismith’s Christian vision. “I’m sure,” Naismith wrote near the end of his life, “that no man can derive more pleasure from money or power than I do from seeing a pair of basketball goals in some out of the way place—deep in the Wisconsin woods an old barrel hoop nailed to a tree, or a weather-beaten shed on the Mexican border with a rusty iron hoop nailed to one end.”

Naismith’s story is worth celebrating as we watch the Knicks and Pacers battle for the 79th NBA title.

Originally published in Newsweek

We publish a variety of perspectives. Nothing written here is to be construed as representing the views of The Daily Signal.