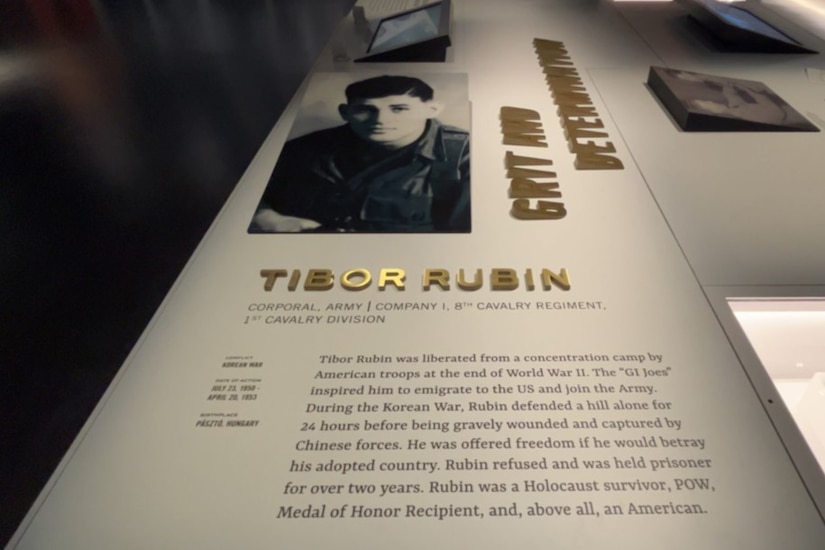

Few, if any, Medal of Honor recipients endured what Army Cpl. Tibor Rubin did.

As a young Jewish man in Europe during World War II, Rubin survived the Holocaust before moving to the U.S. in the hopes of joining the Army to pay back the country that gave him freedom. He served valiantly during the Korean War only to be taken prisoner again. In 30 months of captivity, Rubin’s leadership, spirit and actions were credited with saving the lives of dozens of fellow prisoners, all of whom said they wouldn’t have survived without him.

Rubin is the only Holocaust survivor to receive the nation’s highest medal for valor.

Rubin was born June 18, 1929, in Paszto, Hungary. His father, Ferenc, served with distinction in the Hungarian army during World War I, including as a Russian prisoner of war for six years, before working as a shoemaker. Rubin’s mother died of cancer when he was young, so he was raised by his stepmother, Rosa, alongside his two brothers and three sisters.

When the Nazis rose to power in Germany, the family fell victim to the horrors that all European Jews experienced during World War II. Rubin’s stepmother and sister, Elonja, died in the gas chambers at Auschwitz. His father was also sent to the infamous concentration camp and died in captivity. Rubin’s second sister, Edith, survived the camps, while a third sister, Irene, survived in Budapest, Hungary. Rubin’s eldest brother, Miklos, was forced into hard labor. Another brother, Emory, tried to flee before the same could happen to him, but he was caught and sent to the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. He didn’t survive.

00:15

Video Player

Video Player

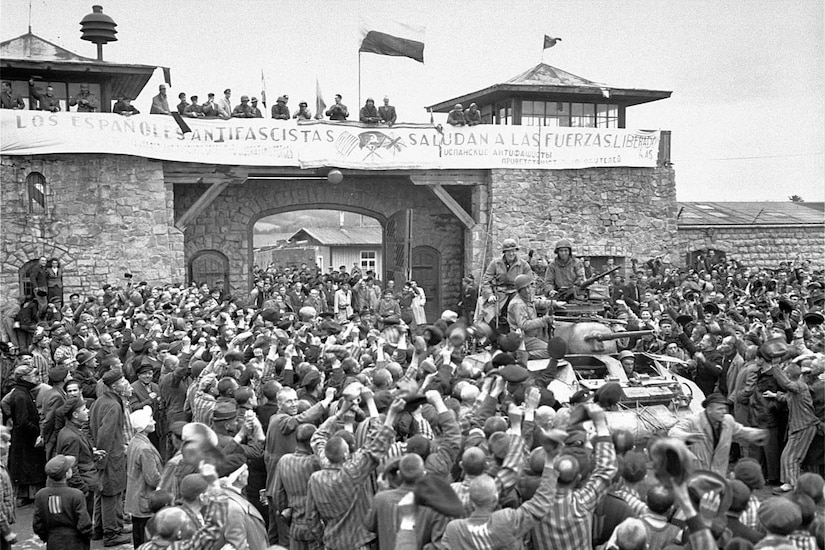

Rubin was sent by his parents with a group of Jews to try to escape via Switzerland, but they were caught. Rubin was forced into Mauthausen when he was just a teen. Later in life, he said he was lucky to find his brother there, who helped him survive. Otherwise, it was a bleak life.

“There was nothing to look forward [to],” he said in a Library of Congress Veterans History Project interview after receiving the Medal of Honor. “Just [thinking], ‘When [am I] going to be next?'”

Rubin spent 14 months in Mauthausen before the camp was liberated May 5, 1945, by the Army’s 11th Armored Division. He credited Army medics with saving many survivors, including himself.

“They picked us up and brought us back to life,” Rubin said in a 2005 interview.

After the war, Rubin made a vow to pay the United States back for its compassion by serving in its Army. After spending nearly three years in a displaced persons camp in Germany, the young man moved to New York in 1948. Known as Teddy in the U.S., Rubin initially worked as a butcher and a clerk. His surviving siblings — Edith, Irene and Miklos — eventually joined him.

Rubin’s first two attempts at passing the Army entrance exam failed because of his poor English. However, after getting some help, he finally passed on the third try.

Rubin first served as a rifleman with the 29th Infantry Regiment in Okinawa, Japan. As tensions in Korea began to rise, the unit was transferred there in preparation for war. However, Rubin was told he couldn’t go because he wasn’t a U.S. citizen. Rubin protested, and eventually leadership gave in. On Feb. 13, 1950, he deployed to the conflict zone with the 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division.

A few months later, full-fledged war broke out between the north and south.

While many Medal of Honor recipients receive the award for one particular action, Rubin was one of the few who earned it for his entire war experience.

In late July 1950, Rubin was with Company I when North Korean troops surged south, forcing his unit to retreat toward the Pusan Perimeter in the southeastern tip of the country. Rubin was ordered to stay behind to keep enemy troops at bay while the rest of his unit withdrew along a vital route.

In the early-morning hours of the ensuing battle, Rubin was the only soldier defending a hill from assaults by an overwhelming number of enemy troops.

“I figured I was a goner,” Rubin said in an Army interview. “But I ran from one foxhole to the next, throwing hand grenades so the North Koreans would think they were fighting more than one person.”

During a 24-hour stand, the corporal inflicted a staggering number of casualties on the attacking enemy and single-handedly slowed their advance, allowing his regiment to successfully withdraw from the danger zone.

On Oct. 30, 1950, during a massive nighttime assault, Chinese forces attacked Rubin’s unit in Unsan, North Korea. For more than a day, the corporal found himself manning his unit’s only remaining .30-caliber machine gun after the three previous gunners fell. He eventually ran out of ammunition, but his determination slowed the pace of the enemy’s advance, which allowed remnants of his unit to retreat.

Unfortunately, Rubin was severely wounded during the fight. By the battle’s end, he and hundreds of other soldiers were taken prisoner and forced to march to a camp known as “Death Valley.” Winter had begun, and the prisoners weren’t dressed to handle the freezing temperatures. They barely got enough food to stay alive, and most suffered from exhaustion, hunger, dysentery, pneumonia and hepatitis. Many died quickly.

When the Chinese learned that Rubin was technically still a citizen of Hungary, which was communist, they offered to send him back. Rubin refused, however, opting to stay in the camp with his fellow soldiers.

During their hardships, the survival skills Rubin had acquired during the Holocaust kicked in. He often sneaked out of the camp in the middle of the night to search for food for his comrades. He would pillage his captors’ gardens and storehouses, despite the risk of torture or death if he got caught.

Rubin also did his best to improve morale by giving pep talks and reminding soldiers that their families were waiting for them. He nursed many of the sick and wounded in the camp. An Army account of his actions stated that he knew what weeds had medicinal qualities, and he knew hope was what the men needed to keep fighting for their lives.

“He saved my life when I could have laid in a ditch and died — I was nothing but flesh and bones,” Army Sgt. Leo Cormier, a fellow POW, later said. “He saved a lot of GIs’ lives. He gave them the courage to go on living when a lot of guys didn’t make it.”

According to Rubin’s MOH citation, his selfless efforts were directly attributed to saving the lives of up to 40 of his fellow prisoners.

In the spring of 1953, after 30 months in POW camps, Rubin was sent back to the U.S. in a prisoner exchange. Despite being nominated four times for the Medal of Honor by fellow comrades, he only received the Prisoner of War Medal and two Purple Hearts.

According to the National World War II Museum, several men in Rubin’s unit claimed that one of their superiors was antisemitic. Those men said that on several occasions, that superior denied their Medal of Honor recommendations for Rubin. Rubin himself said the man would use racial slurs toward him and often sent him on dangerous missions.

Life moved on, however, and so did Rubin. He finally became a U.S. citizen on Nov. 27, 1953, and moved to California to manage his brother’s liquor store in Los Angeles.

“When I became a citizen, it was one of the happiest days in my life,” he said.

In 1963, Rubin married a woman named Yvonne. They had two children; a daughter named Rosie and a son named Frank, who followed in his father’s footsteps by serving in the Air Force.

In the 1980s, for the first time since the war, Rubin met up with some of his fellow POWs from Korea. That meeting seemed to jog the memories of his comrades, who soon after began to petition the Army to recognize Rubin for his immense bravery during the war.

In the early 2000s, after many efforts, a Congressional review was ordered of Jewish and Hispanic personnel records spanning World War II-Vietnam to see if any service members had been passed up for higher honors because of prejudices. One of those records that was reviewed and approved was Rubin’s.

On Sept. 23, 2005, a 76-year-old Rubin received the Medal of Honor from President George W. Bush during a White House ceremony. Bush called it a debt “that time has not diminished,” despite the 55 years that passed since Rubin’s days in battle.

Rubin, however, was quick to brush off the praise.

“The real heroes are those who never came home. I was just lucky,” he said. “This Medal of Honor belongs to all prisoners of war, to all the heroes who died fighting in those wars.”

Rubin died Dec. 5, 2015, in Garden Grove, California. He is buried at Mount Sinai Memorial Park in Los Angeles.

In June 2022, Rubin’s family donated his Medal of Honor to the 1st Cavalry Division during a special transfer ceremony. The medal is now on display at the division’s headquarters in Fort Hood, Texas.

This article is part of a weekly series called “Medal of Honor Monday,” in which we highlight one of the more than 3,500 Medal of Honor recipients who have received the U.S. military’s highest medal for valor.

Source: Department of Defense

Content created by Conservative Daily News is available for re-publication without charge under the Creative Commons license. Visit our syndication page for details.