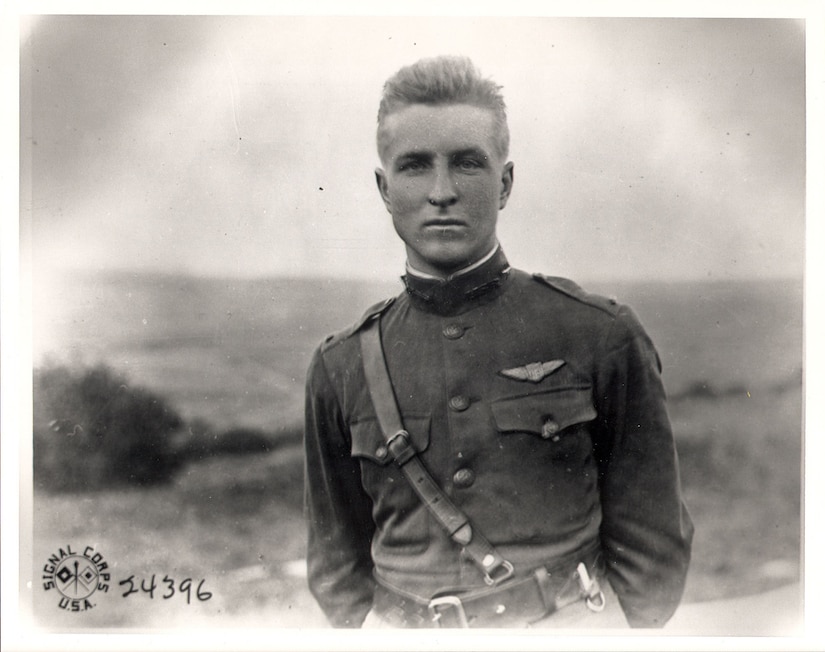

Aviation was in its infancy during World War I, but Army 1st Lt. Frank Luke Jr. took to it like a duck to water. Earning the nickname the “Arizona Balloon Buster” for the high number of enemy observation balloons he shot down, Luke was known as the most spectacular air fighter of the war. He didn’t make it home, but his heroics in the sky made him the first Army aviator to receive the Medal of Honor.

Luke was born May 19, 1897, in Phoenix. He was the fifth of nine children born to his parents, Tillie and Frank Luke Sr.

Luke grew into a strong young man. He was known as one of the best athletes at Phoenix Union High School, where he was the track team captain and a member of the basketball and football teams. According to a speaker at his Medal of Honor ceremony, one time he even saved the life of a friend who was struggling to cross a stream when they went camping.

In September 1917, a few months after the U.S. entered World War I, Luke enlisted in the Army Signal Corps’ Aviation Section, which transformed in April 1918 to the Army Air Service. Luke learned to fly aircraft at Rockwell Field in San Diego, receiving his wings and a commission to second lieutenant in January 1918.

Soon after, Luke was sent to France for additional combat training, which he completed in May 1918. From there, he went to Cazaux, France, to serve on the Western Front with the 1st Pursuit Group, 27th Aero Squadron. On Aug. 16, 1918, Luke took down his first enemy aircraft in combat.

In the short amount of time Luke spent overseas, he earned the reputation of being a bit of a loner who occasionally ignored orders and sought to destroy the enemy on his own. He did, however, team up with a friend, Army 1st Lt. Joseph Wehner, during the mid-September St. Mihiel Offensive. During that time, Luke shot down three aircraft, and the pair destroyed five German observation balloons, which Luke attacked frequently.

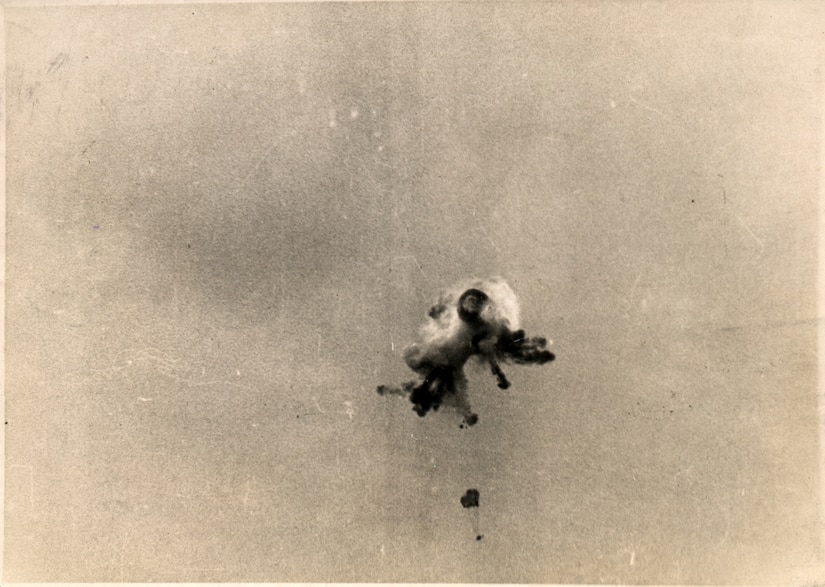

While tethered balloons don’t sound like a difficult target, they were one of the toughest any pilot could face during World War I. The hydrogen-filled balloons were critical to the war’s trench warfare environment, serving as observation posts that enabled both sides to look deep behind enemy lines. Observers in the balloons communicated with their leaders and adjusted artillery fire on the ground in real time to increase accuracy.

Because the balloons had such great tactical value, most were protected by heavy antiaircraft gun batteries, and there were often squadrons of airplanes ready to pursue anyone who considered going after them. Pilots who continually targeted the balloons were considered to have a death wish, historians said.

Luke’s last flight — and his most valiant — happened on Sept. 29, 1918, near Murvaux, France. That day, he took to the skies in a French-built Spad XIII aircraft to go after enemy observation balloons, even though he hadn’t received the proper permission, according to Air Force historians.

When Luke neared the enemy balloon line, eight German planes that were protecting it came after him. Despite the heavy fire he took from those planes and the ground batteries below, Luke didn’t hesitate to attack back, shooting down three balloons. He then descended to within 50 meters of the ground and, with at least a dozen villagers watching, opened fire on enemy troops, killing six and wounding many more.

During the melee, Luke was also hit and severely wounded in the right shoulder. He was then forced to make an emergency landing in hostile territory. Surrounded by German forces on all sides who called on him to surrender, Luke refused. Instead, he drew his automatic pistol and fought back until he was killed.

In Luke’s brief career, he took down four airplanes and 14 balloons. His record of 18 “kills” stands second only to Army Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker’s 26, according to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

Aside from the French villagers who made a sworn affidavit to what they saw Luke do that day, the fallen aviator’s comrades also couldn’t say enough about his bravery.

“No one had the sheer contemptuous courage that boy possessed. He was an excellent pilot and probably the best flying marksman on the Western Front,” said Army Maj. H.E. Hartney, Luke’s commander. “We had any number of expert pilots, and there was no shortage of good shots, but the perfect combination — like the perfect specimen of anything in the world — was scarce. Frank Luke was the perfect combination.”

On May 29, 1919, Luke’s father received the Medal of Honor on his son’s behalf from Army Brig. Gen. Howard R. Hickok. Luke, who also received two Distinguished Service Crosses, was then posthumously promoted to first lieutenant.

Rickenbacker also received the Medal of Honor for his actions during the war, but it wasn’t awarded to him until 1930.

Luke was initially buried by the Germans in the area where he fell; however, he was later moved and buried in a grave in the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, France.

His Medal of Honor was donated to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio.

Luke’s valor has certainly not been forgotten. On Armistice Day in 1930, before it became known as Veterans Day, a statue of his likeness was unveiled at the grounds of the Arizona State Capitol building in Phoenix. Luke Avenue on Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska, was also named for him.

But perhaps his best-known namesake would be the one right near where he grew up: Luke Air Force Base outside of Phoenix was named in his honor in 1949.

This article is part of a weekly series called “Medal of Honor Monday,” in which we highlight one of the more than 3,500 Medal of Honor recipients who have received the U.S. military’s highest medal for valor.

Source: Department of Defense

Content created by Conservative Daily News is available for re-publication without charge under the Creative Commons license. Visit our syndication page for details.