New York CNN —

Parents aren’t alone in feeling the extra pinch in the wallet this year in paying for back-to-school necessities. Teachers, too, are digging deeper to meet their classroom needs out of pocket.

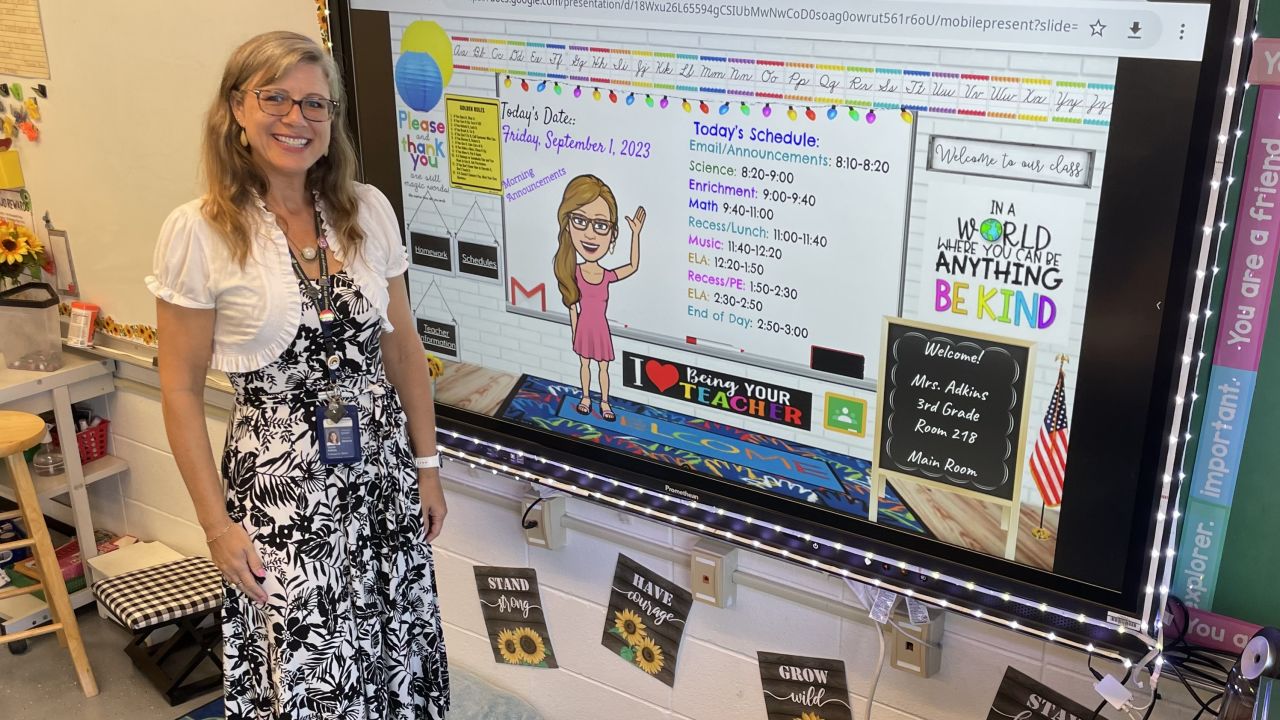

Sarah Adkins, a third grader teacher with Pennoyer School District 79, a Northwest Chicago surburban elementary school, spends an average of $300 to $500 a year of her own money — without reimbursement — on supplies, teaching resources and decorations to make her classroom less bare and more warm and inviting to her young students.

“I recently spent $40 on balloons and a T-shirt so we could celebrate the third day of third grade in style,” she said.

As the year goes on, her personal expense climbs to over $1,000. She expects it to be over $1,000 — on top of any limited classroom budget provided by the school — this year as well.

“I have daughters in college. So this adds up when your personal finances are already stretched,” she said.

“The teaching profession is a real struggle. It’s why there’s a mass exodus happening. You don’t make a lot of money as a school teacher. Why do I do this, especially as it affects my own family financially? You do it for the love of kids and the job,” said Adkins, who’s been a teacher for 26 years.

In February 2023, there were nearly 150,000 more openings in public education than hires, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. As more teachers quit over low salaries and other concerns, it’s exacerbating the ongoing teachers shortage in the United States.

More than 90% of teachers spend their own money on school supplies and other necessities for their students every year, according to the National Education Association, the largest teachers union in the country — and the amount they spend has steadily been creeping higher. Just before the pandemic, teachers spent an average of $500 out of pocket. That number is expected to be considerably higher for the 2023-24 academic year, reaching $800 or more, according to the NEA.

At the same time, a separate report by online learning platform Study.com found that nearly 70% of teachers cited persistent inflation as having a noticeable impact on their ability to afford classroom supplies on their own this year.

Most school supplies have jumped in price, sending the cost of writing tools and supplies such as crayons, pens, and pencils up nearly 19% year-over-year. Consumer price inflation remains elevated, but has come down considerably since hitting 40-year highs last year. The Consumer Price Index — a key inflation gauge that measures price changes for a basket of goods and services — in August measured 3.2% for the year ended in July. That’s down measurably from the 9.1% annual increase registered in June 2022.

Jamesha Gilliam, a public high school English teacher in Marion County, Florida, keeps a locker in her class filled with pens, pencils, notebooks, glue sticks and other stationery materials.

“I use my own money to keep it filled up during the year,” said Gilliam. But she was hit with sticker shock when she recently went to buy a bulk supply of unsharpened pencils. “I would get a 50-pack box for $10, and this year it’s closer to $25,” she said.

Last year, Gilliam spent about $1,000 stocking up on school supplies. “It’s a lot of money to replenish for the year. It’s not only supplies. I buy books, too,” she said. “I bought ‘The Great Gatsby’ for my entire class because I wanted them to be able to mark it up with their own notes. It was expensive but I want to try to go above and beyond.”

Still, the extra investment is a stretch for her. “I work a second job as a server and it provides some supplemental income,” she said. “Rent, morgtages, groceries, everything we need to live is more expensive. I am single with no kids and I still feel it.”

Compensation for educators has flat-lined in the past two decades when adjusted for inflation, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The NEA reported that national average public school teacher salary in 2021-22 increased 2% from the previous year to $66,745 and is projected to grow a further 2.6% in 2022-23.

But average teacher pay has trailed inflation over the past decade. Adjusted for inflation, teachers on average are making $3,644 less than they did 10 years ago, the NEA said.

Layered on top of low salaries, burnout and safety are other reasons why educators are leaving the profession at a faster clip than new hires coming into the field.

In rural communities, the challenge to meet students’ and educators’ needs can be even more pronounced.

Bryan Glahn and his wife both teach in rural Shickshinny, Pennsylvania. Glahn teaches social studies and American history to high schoolers at the Northwest Area School District.

It’s Glahn’s 22nd year as a teacher at the school, which is located about 30 minutes away from where he grew up.

“It’s a real struggle here. It’s a small community that’s strapped for money. The median income is pretty low, between $30,000 to $40,000 a year,” Glahn said.

“There’s not much of a tax base either. There’s no major industry or employer. We had a grocery store that closed years ago,” he said. “There’s a few bars, a pizza shop, ice cream shop and a hardware store.”

The school has a small budget for yearly supplies, “but I find it easier to just buy the things I need,” he said. He recalls teachers having bought a TV and a projector on their own for the school.

Glahn himself spends a few hundred dollars before the start of the new school year to purchase teaching and project materials.

But in a community like Shickshinny, teachers personally pitch in for other needs as well. “If we have a field trip coming up and a student can’t afford it, teachers chip in and don’t tell anybody.”

At times, a student’s needs become more personal — food and clothing.

“We dig deep as teachers. It’s not something we advertise. We do it behind closed doors,” he said.