CNN —

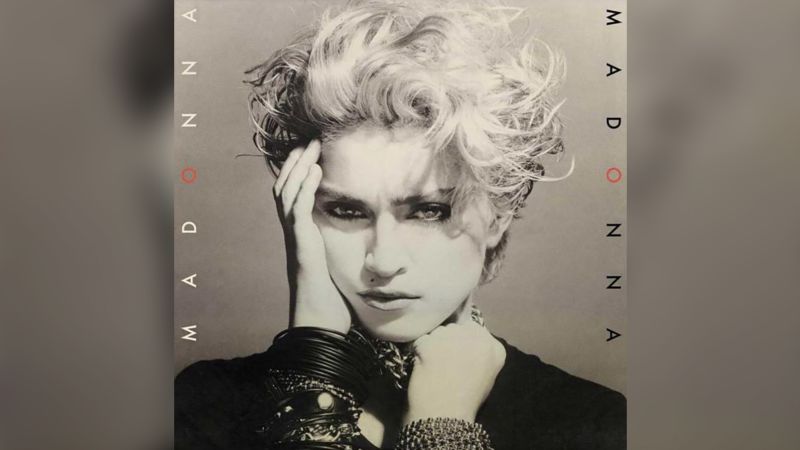

Madonna’s self-titled first album was released 40 years ago this week.

In a social media video she shared on Thursday, the pop culture icon marked the anniversary by dancing to “Lucky Star,” the fourth single from her 1983 debut album, which was also her first top-five Billboard hit in the US.

“To be able to move my body and dance just a little bit makes me feel like the Luckiest Star in the world!” Madonna wrote, referencing her recovery from a medical issue earlier this summer. “Thank you to all of my fans and friends!”

Those friends include Michael Rosenblatt, the former A&R man at Sire Records – Madonna’s first label – who helped launch her career.

“I gave Madonna – after we signed – I gave her a gift of one of these old school Casiotone keyboards with a cassette player built in,” Rosenblatt told CNN in a recent interview. “And a week or two – definitely not longer than two weeks after I signed her – she came into my office and she played me ‘Lucky Star.’ She said, ‘I just wrote this on this little thing’ I got her.”

“I told her she wrote her first hit,” he recalled.

But luck had very little to do with the future Queen of Pop’s initial rise to fame, the kind of storied journey that has generated as many versions as those who tell it. One through-line, however, is that Madonna herself always seemed to know exactly where she was headed.

“I was so impressed with her from the first time I met her,” Bobby Shaw – who worked in the world of music promotion in early-1980s New York City and was the first promoter of Madonna’s music – told CNN. He also called her a “go-getter” who was “really aggressive” in wanting to know all about the business.

“Madonna” the album served as an explosive entry for the trained dancer-turned-singer on the road to being so much more. Although the album only contained eight songs total, those songs – including additional singles “Borderline,” “Burning Up” and “Holiday” – embodied the young and exuberant New York club culture of the time.

Danceteria, a dance club in Manhattan’s Garment District from 1979 to 1986, served as one of the nexus points for the burgeoning music scene in the city. A then 24-year-old Michigan native who had already tried to put together a record in Paris, Madonna was known to frequent the spot – she even said she “stalked” a DJ there in a recent Instagram post.

“My best friend at the time was Mark Kamins, who was the Friday, Saturday night DJ at Danceteria” Rosenblatt recalled. “And he told me about this girl who kept coming by trying to get him to play her demo – which he wouldn’t. But he told me this girl was just incredibly hot.”

One Saturday night in the winter of ’81-‘82, he would finally meet Madonna, coincidentally while he was accompanying another duo of artists who recently had been signed by a friend of his in England – namely, Wham!.

“So I’m out that night with George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley, taking them to various clubs. And we’re at Danceteria, we’re at the second floor bar area, which is where Mark Kamins was the DJ. And I saw this girl go across the dance floor and up to the DJ booth and I said to myself, ‘That’s gotta be this girl that Mark’s talking about,’” Rosenblatt said, going on to mention that the two started talking, and made an appointment that Monday for Madonna to play him her demo. (The demo, he later said, contained the track “Everybody” – which would eventually become “Madonna’s” lead single, along with a B-side titled “Ain’t No Big Deal.”)

“So Monday, end of the day, Madonna and Mark showed up at my office and played me her demo, which was good. I mean, it wasn’t f–king amazing, but it was good,” he continued. “But what happened was, there was a star radiating in my office. It was her.”

Rosenblatt knew from the get-go that he was dealing with someone special, but he had one more test up his sleeve to spring on the neophyte.

“I always ask this question – and I still do with any artist I’m interested in – (which) is, ‘What do you want? What are you looking for?’” he explained. “The wrong answer is, ‘I want to get my art out there.’ The best answer was the one Madonna gave me, which said, ‘I want to rule the world.’ And I thought, that’s a hell of an answer.” (As it happens, it’s also the answer Madonna famously gave Dick Clark on “American Bandstand” in 1984.)

Rosenblatt’s instincts kicked in, and he wanted to move fast in securing a deal with Madonna. Which meant talking to his boss, Sire Records president Seymour Stein, and setting up an appointment for the two to meet the very next day – even though Stein was in the hospital at the time for a heart-related issue. (Stein lived for much longer, though, and passed away earlier this year).

“I went up to see Seymour, played him the demo, told him all about her, that she’s just a f–king star and we gotta sign her,” Rosenblatt recalled.

But there was still one thing that stuck out for him.

“I told Madonna, ‘You have to bring some ID, because I don’t believe your name is Madonna.’ And she said, ‘What are you talking about?’” he said, adding that he replied to her at the time that it was “just too good to be true. It’s like, it’s perfect.”

“And she came up the next day with her passport!”

As with many parts of Madonna’s origin story, that meeting with Stein at the hospital has become the stuff of legend. There was a boombox in the room, and Rosenblatt played her demo again for Stein while Madonna was there. Beyond her music, the clincher was the artist standing there who was ready to take on the world.

“We listened to the music again and Madonna charmed the hell out of him,” Rosenblatt said of that fateful day with Stein. “She knew that she was this close to getting a deal, and this was the guy who was gonna make it happen.”

And while “everybody hit it off,” Rosenblatt still wasn’t fully confident that Stein would agree to sign her, because, he said, nobody else wanted to sign Madonna at the time. (The singer herself has spoken of the professional rejection she experienced in her early years in New York.)

Rosenblatt said it had to do with just how novel Madonna really was – not only in terms of her personality and (later, oft-imitated) presentation – but also because her music differed from what was popular at the time.

“You think about that genre, it hadn’t happened yet,” he said of Madonna’s early sound.

“There was disco, and there was new wave. And there was nothing in the middle, you know what I mean? So nobody was interested,” he added, going on to say that it was “also maybe because she didn’t have a manager or lawyer out there shopping. She was just this club kid.”

“Madonna was really coming out of the new wave clubs in a way that never really happened before,” he later said. “I mean, Debbie Harry was huge, but nobody was doing the disco/new wave thing, (the) R&B thing the way Madonna did. I mean, we created a format. But before that it didn’t (exist).”

Still, Rosenblatt knew a star when he saw one, and Stein agreed. He said yes to signing her for a singles deal – “a $10,000 singles deal” – that day in hospital. Rosenblatt and Stein had a strategy, knowing that the singles deal would eventually lead to a full-on record contract down the road.

“We went into the studio with Mark Kamins to cut ‘Ain’t No Big Deal,’ as the A-side, and ‘Everybody’s’ the B-side.” Rosenblatt said. “‘Ain’t No Big Deal’ did not come out well. So we just went with ‘Everybody.’ And I remember going into Bobby Shaw’s office because we’re all psyched about ‘Ain’t No Big Deal.’ And I said, ‘Well, that didn’t come out well. Is ‘Everybody’ strong enough for you?’ He goes, ‘Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.’”

Shaw explained that his decision to promote “Everybody” was a little unorthodox, since there was still no album secured yet behind it.

“Back then, unless there’s an album to back it up, the record companies aren’t going to spend a lot of money to try to get it on radio,” he explained.

Still, they went for it.

”(‘Everybody’) was a good record. It’s pretty simple,” Shaw said. “The song was great. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure that out.”

Additionally, much like Rosenblatt, Shaw had more than a hunch that the person singing the song was going to be a big deal.

“I knew before this first song that (Madonna) was somebody special,” Shaw said. “The music had to be good, but nonetheless, the first song was great. I loved it. And I mean, it made noise. It made noise enough to give her an album deal.”

Madonna collaborated with a string of producers that included Kamins, Reggie Lucas – with whom they cut the song “Physical Attraction,” “which we loved,” Rosenblatt said – and John ‘Jellybean’ Benitez on her first few singles.

“So we made the album and it had ‘Borderline,’ which I knew was a smash. It had ‘Lucky Star,’ which I thought was gonna be a big hit, but it didn’t have what I wanted to be the lead off, just stone cold hit,” Rosenblatt said. “And I went to Seymour and I said, ‘Dude, I need another $10,000 to do another song.’”

Stein told him that in order to secure that additional funding, they would have to go to Los Angeles to meet the the top brass at Warner Bros. Records (now Warner Records) – Sire being a subsidiary of that company.

“I just knew that if I were to take Madonna out to LA to meet Warner Bros., getting the money would be no problem,” Rosenblatt said.

The pair traveled out to the West Coast, and stayed at Rosenblatt’s parents’ house, where Madonna invariably caught the attention of his mother.

“We’re getting ready to go out to meet the Warner crew,” Rosenblatt recalled. “My mom pulls me aside before we leave and goes… ‘Do you think you should tell Madonna to take the rags out of her hair before you meet Warner Bros.?’” – a clear reaction to the future star’s style that would soon take youth fashion by storm.

“And I said, ‘Thanks for caring mom, but we’re good!’” Rosenblatt added with a laugh.

Of course, the meetings with the top brass went well – their trip even coincided with the Passover holiday, Rosenblatt shared, and Madonna ended up as a guest at the Seder with Rosenblatt, his family, and some of the WB music execs, including Mo Ostin, at the legendary Chasen’s Restaurant, where she sang verses of the Haggadah (Passover prayer book) while wearing her trademark crosses.

“We met everybody and everybody loved her, everybody just loved her. Everybody got it,” Rosenblatt said. “She just charmed everybody. And at the end of the day before we left, I ran up to Lenny Waronker, who was the president of Warner Bros. at the time, (and) I said, ‘I need $10,000 to do one more song. I just need that lead out single.’ He said, ‘You got it.’ So the trip was a success.”

Back in New York, Rosenblatt came to Lucas, Benitez and Kamins with a proposal.

“I said, ‘Look, whoever comes to me with the song gets to produce it, I have $10K to cut a song.’”

Four days later, he said Benitez came in with a demo version of a song called “Holiday.”

“Sung by a guy. Much slower. But I love the song,” Rosenblatt recalled, adding how they proceeded to “speed it up and make it a dance record.”

“Holiday” – to this day one of Madonna’s most well-known anthems – was the surefire element Rosenblatt thought they needed to finish the album.

Then came the time to promote it, which wasn’t exactly in the bag yet. Shaw remembers how he and Madonna went down to Florida on a publicity tour, and drove around in “a beautiful convertible” while her brother, then-dancer Christopher Ciccone, and two other backup dancers traveled separately.

“We were listening to music while we were driving. And I was smoking pot and she wasn’t smoking,” Shaw recalled of their drive to Key West from Fort Lauderdale. “And then that night it poured. We did the Copa in Key West.”

Before the show, Shaw remembers sitting in one of their hotel rooms, watching the group rehearse. This was before Madonna was the Madonna the world eventually came to know, so sometimes the shows they played were for only a couple dozen people.

“I look back at this now, it just seems so surreal. But I was sitting on the edge of a bed watching them practice dancing in a hotel room. And it poured that night and maybe 25 people came to the venue. She was nobody. Nobody knew her then. We were trying to break her. So it was grassroots, ground up.”

Things changed, of course, thanks to the singles from the “Madonna” album picking up airplay on the radio and her music videos finding heavy rotation on the still new MTV. Madonna had a prescient attitude to music as a visual medium, quickly embracing the music video format when more established musicians initially balked at the concept.

“When ‘Holiday’ just started to break, and then ‘Borderline,’ and then it was, like, over,” Rosenblatt recalls of the moment when the scales tipped and Madonna started to catch on. “And I think the record just started to explode.”

This was still 1983, before Madonna’s smash sophomore album “Like A Virgin” and her now-legendary performance at the first-ever MTV Video Music Awards in September 1984, a showstopping display that made everyone who wasn’t already start paying attention.

Looking back, Rosenblatt remembers telling Stein that Madonna was going to “be the biggest artist” he would ever work with.

“And he’s like, laughing, he goes, ‘Yeah? How big is she gonna be?’ And I said, ‘Seymour, she’s gonna be bigger than Olivia Newton John,’ who at the time was the biggest selling female artist.”

“I said she’d be bigger than Olivia Newton John and I thought she’d be like Barbara Streisand, because I really saw her acting,” Rosenblatt later added. “But who knew she was going to be this cultural idea, who knew she was going to be Marilyn Monroe. She became this cultural icon and that I don’t think anybody saw coming. But I knew, and as did Madonna.”

“I went to New York. I had a dream. I wanted to be a big star, I didn’t know anybody, I wanted to dance, I wanted to sing, I wanted to do all those things,” Madonna said of her meteoric rise in a 1985 concert documentary. “I wanted to make people happy, I wanted to be famous, I wanted everybody to love me. I wanted to be a star. I worked really hard, and my dream came true.”