Los países de literatura indigente tienen historia desabrida.

[Countries with an impoverished literature have an insipid history.]

— Nicolás Gómez Dávila

It has become something of an autumn tradition. The leaves change their verdant hues, mothballed sweaters come out of storage, pumpkin spice is liberally sprinkled over food and drink, and it is also around this time of year that libraries, bookstores, and publishers engage in the virtue-signaling exercise known as “Banned Books Week.” Launched in 1982 with the goal of highlighting “the value of free and open access to information,” Banned Books Week in its present form has little to do with truly banned books, like the religious literature that can land one in prison in totalitarian regimes like China, North Korea, or Russia. Its emphasis, instead, is on “challenged” or “restricted” books closer to home. An overly concerned parent in a Texas school district requests that Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 be withdrawn from circulation due to its “dirty talk” and depiction of a burnt Bible, the school board declines, and — voilà — you have a “challenged book,” which is then mysteriously transmuted into a “banned book.”

READ MORE from Matthew Omolesky: The Painter and the Chatbot: Artificial Intelligence and the Perils of Progress

As anyone whose address is on an independent bookstore’s e-mail list knows, booksellers have wholeheartedly embraced Banned Books Week, albeit from a cynical marketing perspective, offering customers that particular frisson that comes from consuming supposedly illicit, but actually quite anodyne, reading material. Public librarians, lacking a direct profit motive, view the occasion more in terms of social engineering and ideological indoctrination. My own local library erected a display during this year’s Banned Books Week, which was observed during the first week of October, featuring underground samizdat works such as Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games. Meanwhile, one notes with interest, a Chinese Christian in the Inner Mongolian city of Hohhot by the name of Wang Honglan currently languishes in jail, his alleged crime being the distribution of perfectly legally printed Bibles to members of what turned out to be a prohibited house church. The same fate is unlikely to befall someone in the United States selling or possessing, say, the “challenged” or “banned” (yet somehow bestselling) young adult epistolary novel The Perks of Being a Wallflower.

There is a further sleight-of-hand at work here. Visit the Banned Books Week website, maintained by the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, and you will find that the most challenged books of 2023 are Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer and George Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue, titles the reader may recall from the notorious Sept. 12, 2023, Senate Judiciary Committee hearing “Book Bans: Examining How Censorship Limits Liberty and Literature,” during which Sen. John Kennedy recited a series of extraordinarily graphic passages from those selfsame “coming-of-age” young adult novels. The American Library Association informs us that these works are “claimed to be sexually explicit,” which is a bit like saying that I Spit on Your Grave is “claimed to contain graphic violence,” or that A Serbian Film is “claimed to contain depictions of sexual violence and child abuse.” As Kennedy put it, “We’re not talking about Catcher in the Rye” here.

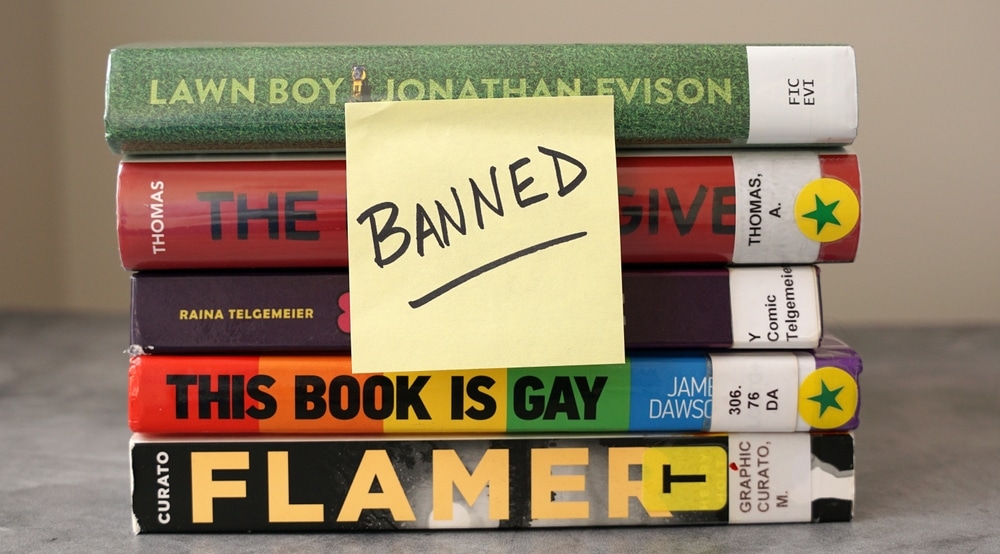

It would have been rather more honest had public libraries and bookshops instead exhibited Gender Queer, All Boys Aren’t Blue, Flamer, Looking for Alaska, and This Book is Gay during Banned Books Week, but this would have been giving the game away. Instead, Illinois Secretary of State Alexi Giannoulias, who was being questioned by Kennedy regarding an Illinois law that would withhold state funding from libraries failing to follow the American Library of Association guidelines on “censorship,” continued to trot out worn-out examples from decades past: “When individual parents are allowed to make a decision of where that line is and To Kill a Mockingbird, which involves a rape scene, should that book be pulled from our libraries? I think it becomes a slippery slope.” The ongoing culture war over school library holdings — primarily waged over works that contain material either appealing to prurient interest or containing provocative “LGBTQIA+” content — no longer concerns works like Fahrenheit 451, Catcher in the Rye, To Kill a Mockingbird, or Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Those controversies, such as they were, represent artifacts from the early days of Banned Books Week.

All the same, neither the American Library Association’s suggested Library Bill of Rights nor the Illinois HB 2789 legislation banning book bans bother to mention lewd content. Instead, the stress is laid on “free expression and free access to ideas.” Under the so-called Library Bill of Rights, “[m]aterials should not be excluded because of the origin, background, or views of those contributing to their creation,” and “[l]ibraries should provide materials and information presenting all points of view on current and historical issues. Materials should not be proscribed or removed because of partisan or doctrinal disapproval.” This sounds like a libertarian’s paradise, where no ideological holds are barred, and Mein Kampf and The Protocols of the Elders of Zion can rest comfortably on the shelves next to The Anarchist Cookbook and David Duke’s Jewish Supremacism: My Awakening on the Jewish Question. It seems quite safe to day, however, that nobody takes these blanket assurances of content neutrality seriously. There is always a line to be drawn. There are books that are patently offensive, or obscene, or prurient in nature, or wholly lacking in serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value, that have no place in a school library. A public library might have a manga section, but hentai manga will naturally be excluded. A public library will rent out DVDs and provide options for content streaming (Kanopy, Hoopla, etc.), but I doubt you will be able to find the disgustingly anti-Semitic Egyptian series Horseman Without a Horse (based on The Protocols of the Elders of Zion) readily available on those platforms. Does this constitute “partisan or doctrinal disapproval”? Are those libraries “presenting all points of view on current and historical issues”? There is a reason why libraries are expected to conform to “community-based standards.” The real question is what even constitutes a community in a country riven by fundamental partisan and ideological divisions.

*****

While conservatives and LGBTQIA+ activists debate the that renders the premise of Banned Books Week largely irrelevant. On Sept. 13, 2023, CBC News reported on a disturbing development in Mississauga, Ontario, where students were complaining about empty bookshelves in their high school library. The students were informed by the library staff that “if the shelves look emptier right now it’s because we have to remove all books [published] prior to 2008.” The liquidation of library holdings was the result of a “new equity-based book weeding process implemented by the board last spring in response to a provincial directive from the Minister of Education,” a process “intended to ensure library books are inclusive” but that “appears to have led some schools to remove thousands of books solely because they were published in 2008 or earlier.”

The Ontario school librarians had been using a manual entitled “Weeding and Audit of Resource in the Library Learning Commons Collection,” which provides an “equitable curation cycle” for “weeding,” first eliminating books based on categories including “misleading,” “unpleasant,” “superseded,” “trivial,” or “irrelevant,” and then further separating the alleged wheat from the alleged chaff through an “anti-racist and inclusive audit” that will have books headed for the recycling bin (once the mylar dust covers are removed) if they are not “inclusive” or “culturally responsive.” Yet the non-profit advocacy organization Libraries Not Landfills has alleged that the weeding process has routinely been conducted with an eye only to the publication date: “Dianne Lawson, another member of Libraries not Landfills, told CBC Toronto [that] weeding by publication date in some schools must have occurred in order to explain why a middle school teacher told her The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank was removed from shelves. She also says a kindergarten teacher told her The Very Hungry Caterpillar had been removed as well.” All of this, of course, is completely idiotic.

Treating the year 2008 as Year Zero for library content purposes may seem baffling, but it is a positively antiquarian approach when compared to the California Department of Education’s recommended reading list. The “English Language Arts/General” list for grades 9–12 contains 58 titles, the very oldest of which is the 2019 novel Unpregnant (“Seventeen-year-old Veronica Clarke never thought she’d want to fail a test — that is, until she finds herself staring at a piece of plastic with two solid pink lines. With a promising college-bound future now disappearing before her eyes, Veronica considers a decision she never imagined she’d have to make: an abortion. There’s just one catch — the closest place to get one is over nine hundred miles away. With conservative parents, a… let’s say less-than-optimal boyfriend, and no car, Veronica turns to the only person she believes won’t judge her: Bailey Butler, a legendary misfit at Jefferson High — and Veronica’s ex-best friend. The plan is straightforward: a fourteen-hour drive to the clinic, three hours for the appointment, and a fourteen-hour drive home. What could go wrong? Not much, apart from three days of stolen cars, shot guns, crazed ex-boyfriends, aliens, ferret napping, and the pain and betrayal of a broken friendship that can’t be outrun. Under the starlit skies of the American Southwest, Veronica and Bailey discover that sometimes the most important choice is who your friends are.”). All the other books, from All My Rage and Brown Girl Ghosted to Not Here to Be Liked and Revolution in Our Time: The Black Panther Party’s Promise to the People, and from This Is My America and Victory. Stand!: Raising My Fist for Justice to When You Call My Name and Zara Hossain Is Here, are from 2020, 2021, or 2022.

In Florida, meanwhile, we find that the B.E.S.T. Standards for English Language Arts includes some contemporary books alongside classical works of literature including Hamlet, King Lear, Pride and Prejudice, Heart of Darkness, Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, and the poetry of John Donne, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Robert Frost, among others. First-year students at the New College of Florida are being offered a course centered around Homer’s Odýsseia, which poses the question “What is the value of challenge, sacrifice, and personal growth?” I am reminded here of the Colombian philosopher Nicolás Gómez Dávila’s observation that “La sociedad moderna desacredita al fugitivo para que nadie escuche el relato de sus viajes. El arte o la historia, la imaginación del hombre o su trágico y noble destino, no son criterios que la mediocridad moderna tolere. [Countries with an impoverished literature have an insipid history. Art or history, man’s imagination or his tragic and noble destiny, these are not criteria that modern mediocrity will tolerate].” California has enthusiastically embraced this modern mediocrity, effectively treating 2020 as its own Year Zero, whereas Florida, under the leadership of Gov. Ron DeSantis and New College of Florida board member Christopher Rufo, is headed in the opposite direction, providing students with an education encompassing the breadth and depth of our collective cultural patrimony.

For all the American Library Association’s talk of “presenting all points of view” while avoiding “partisan or doctrinal disapproval,” we can see that public libraries and schools are being systematically turned into veritable temples of what Wesley Yang has termed “successor ideology” or “successor theology” (and it is here that we remind the reader that the current president of the American Library Association is an avowed Marxist). The cultural frog can be more readily boiled if misleading assertions of ideological neutrality are used to disguise a methodical campaign to “weed” library stacks and school reading lists of books that are insufficiently “inclusive” or “culturally responsive,” or that belong to that long-lost, backward world of more than three years ago. Activist librarians, educators, and administrators are gnawing away at the Western canon like silverfish, and it will take a monumental effort to restore it to its former state. Even then, as Yang has warned, “We haven’t passed peak woke. At best there will be an interregnum of a decade and a half or so until the cohort being indoctrinated from the earliest ages emerges into adulthood,” the cohort that is currently being marinated in the sort of successor ideology embodied by the California Department of Education’s frankly bizarre recommended reading list.

*****

The largely spurious threat of book banning is entirely overshadowed by the very real threat of book weeding, a paradigmatic example of how, to again cite Wesley Yang, “authoritarian Utopianism … masquerades as liberal humanism while usurping it from within.” As successor theology subverts what is left of our collective patrimony, it amounts to what might even be considered a national security threat. A nation draws from a wellspring of shared history, values, and vision for the future, connecting the dead, the living, and the yet unborn, all of which must be inculcated in rising generations from an early age. Benedict Anderson, in his seminal Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (1983), described how our sense of belonging to a nation “is performed in silent privacy, in the lair of the skull. Yet each communicant is well aware that the ceremony he performs is being replicated simultaneously by thousands (or millions) of others of whose existence he is confident, yet of whose identity he has not the slightest notion.” The national community “is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship” for which people must be willing to fight and die if necessary.

A country cannot face an existential threat without this simultaneously deep-rooted and wide-ranging source of comradeship. The Ukrainian soldiers who march off to war against ruthless genocidal invaders make their way to the front while singing Shche ne vmerla Ukrainy i slava, i volia, with its lines about their shared Cossack descent and the sound of freedom that has, from time immemorial, echoed off the Carpathians and rumbled over the steppe. Israeli soldiers headed toward Gaza to avenge the mass murder, rape, kidnapping, and corpse desecration committed by bestial Hamas terrorists sing the Hatikvah anthem, with its expression of the “hope of 2,000 years / to be a free nation in our land.” These are ancient and profound sentiments that immediately overwhelm any sense of peacetime partisan rancor. How many of those steeped from an early age in the toxic brew of successor ideology will be endowed with similar beliefs and able to rise up and meet the noble (and sometimes even tragic) destiny so eloquently described by Gómez Dávila? If entire swathes of the Western world are raised to despise the values and history of their own countries and civilization, how can they possibly form a community capable of confronting existential threats?

To paraphrase Walter Benjamin, works of art tear into you and become lodged in your soul, just as bullets tear into your skin and become lodged in your flesh. Children brought up on a steady diet of All My Rage, while being deprived of any intellectual sustenance from before the woke Year Zero, will find themselves possessed of entirely different worldviews than those who have been raised on Homer and Shakespeare and Austen and Conrad and Frost. It will eventually be like looking at two completely different civilizations, with devastating consequences for our national unity, social solidarity, group consciousness, shared purpose, and overall asabiyyah. Tear down statues of Jefferson, and then even of Washington and Stuyvesant, empty the libraries, replace the curriculum with successor theology, and you may be surprised how quickly you reap the consequences. At the very least, you will certainly discover that a nation is not merely an amorphous, pulsating mass of GDP. Purblind presentism has always been an ideological menace, distorting our sense of history and preventing us from placing events in their proper context, but in a world of mounting existential threats, it may be counted as an existential threat in its own right.