A lot of men who have seen combat refuse to talk about it. Which is too bad for both them and for us. PTSD is a very real problem (I have been in combat with at least two people I know of who later killed themselves, including one I interviewed for an article). I think almost everyone who has seen action has an element of PTSD that is permanent. And from what I’ve seen, talking about it helps and bottling it up does not.

But it’s also bad for the rest of us, because we like war movies and games for a reason. It’s the most real reality that exists. Every breath can be your last; you are responsible for the lives of your buddies and the converse, and as Winston Churchill put it, “Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.” (READ MORE from Michael Fumento: Defend Us in Battle: The Incredible Story of Navy SEAL Michael Monsoor)

Also, there’s lots of stolen valor out there. The best way of determining a fake Navy SEAL: if a guy says he is one he probably isn’t. I claim that my first firefight was not just with the SEALs but with Task Unit Bruiser, SEAL Team 3, the most decorated SEAL unit since Vietnam. I suppose that makes me a stolen valor suspect. Except … I have YouTube videos, published photos, and I’ve been writing about them since our meet-up in Ramadi, Iraq, in 2005. They would have cried foul had I been lying.

As a journalist with prior service as an airborne combat engineer, I consider it my duty to keep the deeds of those SEALs and others alive, in print, just as I considered it my duty to go overseas in the first place. But I’m something of a contradiction. I like wearing war-related clothing like my t-shirt and hoodie displaying my airborne unit, in part because Americans are more likely to help me when I’ve been hobbling around with a walker or a cane after a surgery (10 war-related). But then when people ask me about my experiences, I practically snarl. Obviously, that’s neither consistent nor fair.

Maybe I feel my obligation extends to reporting to wide audiences, and not perhaps providing lurid entertainment to individuals. They can stream Saving Private Ryan for that. (Lots of inaccuracies, but that’s par for the course.) And I have written about most of the horrible things I witnessed, except one that exclusively involved me that virtually nobody knows about or ever will. But damn, what about the funny things? Yeah, lots of funny things happen to everyone in war. And I’ve never shared those. Maybe in part because so many make me look inept!

But I’m past that now and I expect everyone who’s been in combat has done stupid things, especially early on. Good training makes a huge difference, but only goes so far. A member of TUB told me that in their first firefight one of them accidentally dropped his magazine. No, I’m not talking about National Geographic. That is, the magazine release button on an automatic weapon is often very close to the selector switch that releases the safety and, depending on the weapon gives a choice of single rounds, 3-round bursts, or full auto. Whether because of nervousness, because we wore gloves even in the scorching heat, or a combination thereof, as the SEAL probably nervously sought the selector he pushed the button releasing the magazine. If those guys can screw up, so can I.

Let’s begin with my mortar experience, which has usually been incoming rather than the more comfortable outgoing. Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), from what I could tell, exclusively used the big ones per the 120mm Soviet bloc style, with a blast radius called VL. That’s short for “very large.” That’s because AQI liked to shoot and scoot from the back of a pickup truck before a counter-battery could hit them. Since you will only be firing a few rounds and won’t be hand-carrying them, naturally you want to use the biggest available.

The first time I got shelled I was asleep in a cot in a building. I woke up, thought “We’re being mortared,” and went back to sleep.

Ah, but the next day the soldiers picked up the pieces and I saw how they break apart. Absolutely devilish. It’s like flint, with sharp edges to shred pink little bodies. Like mine. I also saw the soldiers reinforcing the roofs with sandbags, that told me that where I was sleeping couldn’t take a direct hit. Later when I arrived at Camp Corregidor in Ramadi, comprising mostly 1/506 of the 101st Airborne but also TUB, I saw where two guys got caught outside while taking a smoke. Nothing left where they’d been standing but a red stain. Yes, smoking is bad for your health.

I hope I’ve given a reminder that every veteran’s story is a mix of valor and vulnerability.

Thereafter when mortars made an unwelcome visit at night I quickly tossed all my gear on top of whatever I was sleeping on and crawled underneath. One night the next year I was asleep alone in a trailer and suddenly it started to rock and roll. It was unnerving. I calmly performed my routine and fell back asleep. Next day I remarked to my “handler” that some of those mortar rounds seemed to have landed quite close. He looked at me with a puzzled expression. “Oh, you felt the 155s (155-millimeter howitzers) that we were firing for illumination!” Ugh. But hey, I’m not an artillery man.

Then there was Blackhawk Almost Down.

Because of the ever-present threat of IEDs, for any long-distance travel we used helicopters. In Iraq, usually UH-60 Blackhawks and in Afghanistan usually BH47-D Chinooks because their two rotors handled the thin mountain air better. The doors (or with the Chinook the ramp) are always kept open. This is because if an enemy round penetrates the openings, it gives them a chance to exit rather than ricocheting until they strike something — or someone — vital. So one night just after we took off I see this terrific light show of green streaks just outside one of the doors. I was fascinated; so pretty! Yet I knew what these were. Tracer rounds from a DShK, with bullets both wider and longer than an American .50 caliber machine gun. A single lucky round would have brought down the helo, killing us all. But may as well enjoy the fireworks! (READ MORE: No More ‘Thank You for Your Service’)

Which leads to me having given orders a few times, despite being a civilian. In one case, I was on a Blackhawk next to an obviously terrified little kid of a Marine. I adore flying in helicopters because of how they twist and turn and if you get a good seat you can look out. I saw a lot of Afghanistan through the bay door of Chinooks. (Iraq? Nothing to look at.) Mind, airborne soldiers figure it’s always a thrill to fly any aircraft where you actually land with it. And as I said, especially with birds. (You can call them helos, birds, or choppers. Never call them a copter.)

But they’re also much more dangerous than a fixed-wing plane because they can’t glide. The best you can do is sometimes throw them into a spin to slow the descent. For whatever reason, this poor guy didn’t share my feelings. Indeed, his M-16 was pointed up. That’s a no-no. It’s normally expected to have a magazine locked in case the helo goes down but you survive. But if you also load a round into the chamber and you have that rifle pointed up, there’s an admittedly small chance you can accidentally fire a round into the rotor.

So I smacked his helmet, smacked his rifle, and did a whirling motion with my arm. Message received. And better from me than his squad leader!

There were a few other minor things like that; when someone tells you to do something smart you don’t look for rank. Good thing for me because I initially just wore khakis, then later the digital BDUs that I had with a tag above the pocket that read “CIVILIAN.” But the real doozy occurred when I visited an Iraqi camp that had been attacked the night before. The commander proudly relayed how his men had driven off the bad guys, then quit, leaving it up to Marines from somewhere else to pursue them. “It’s not your job to drive them off!” I barked at him. “You pursue them and you kill them!” His smile dropped to the floor. Then I remembered I was indeed just a journalist. Not even allowed to carry a weapon. But maybe I put the fear of Allah into him. Then again, probably not.

I guess it was the next night that I listened to a terrific nighttime firefight from a camp. It was usually hard to pin down enough bad guys to fire off so many rounds, but this time we got them! Except we didn’t. It was blue on blue. Iraqi Army on both sides. I watched the base commander screaming into the phone demanding that they cease fire, finally threating to call in an airstrike “if you don’t knock it off.” After which they did, but maybe because they ran out of ammo.

Next day I visited the site and saw these massive piles of ammo casings behind the machine guns. “How many casualties?” I asked mournfully. None. No dead, no wounded. Ineptitude has its bright spots.

And yes, our Iraqi allies were generally Keystone Kops in camo. They loved to “carry” their rifles with the muzzle balanced on the toe. I have pictures of them doing that during combat! (“Do they ever accidentally blow their toes off?” I asked a soldier. “Yup!”)

Once at an isolated camp there were just a few Americans and a squad of cherry Iraqis. It’s the only time I was asked to carry a weapon, because there just weren’t enough guys who actually knew how to shoot. One of the Iraqis, a pudgeball who obviously had connections, had a wire stock on his AK-47. Those are favored because they’re much lighter than those with the typical wooden stock and because the wire ones can fold and that can be more comfortable in close quarters. Fortunately we weren’t ambushed by anything other than hundreds of howling feral dogs.

So we get back and now it’s time to clear the weapons. What’s most important is to point the muzzle at the ground, so you can screw up everything else but if you shoot anything it will just be sand. But the pudgeball with the wire stock was yanking on the bolt pointing the rifle in every direction but the ground. I dropped to the pushup position and sure enough “Crack!”

Fortunately, the bad guys normally weren’t of special ops quality, either. Except the snipers, of whom I’m convinced some were imported from other places like Chechnya. (In the movie American Sniper, with TUB member Chris Kyle, his nemesis was a Syrian gold-medal winning marksman. In fact if the guy ever really existed, Kyle said, someone else must have taken him out.) Point is that the good snipers were usually foreigners. And they like journalist meat. We stand out with our camera bags and sometimes have to stand still when it isn’t safe. Plus plugging a journalist can be international news. Just a soldier, meh.

When I got to Corregidor, I presumed I was the first civilian reporter in all of Ramadi because I never saw any news reports from there except those provided by local stringers. It was one of my motivations to go there and to this day soldiers and SEALs express to me their appreciation. But in the event, when I arrived at the HQ and was briefed by commander Colonel Ron Clark (Now a 3-star general, with so many ribbons on his chest there’s no room for any more), he informed me I actually had two predecessors. Both sniped.

One was an idiot wedding photographer who was actually setting up a tripod in the middle of the street. Like at a wedding, natch. He got shot in one leg, a sergeant from the 101st tried to drag him to safety and was severely wounded. Then the sniper shot the wedding photographer in the other leg just for fun. That’s an expert sniper technique that you’ve seen if you’ve watched Full Metal Jacket. That’s why I think that particular sniper came from some other country.

So time and again 101st soldiers told me about the wedding photographer and another reporter who apparently didn’t do anything stupid but was also shot. The round went into the second photographer’s side, tumbled, and popped out his chest like a tiny little Alien. But he too survived.

In the event, when the SEALs saw me they were not happy. Just another guy to drag to safety. As we were running upstairs to grab the high ground one of them slammed me against the wall. “WTF, bro!” I thought. “Aren’t we on the same side!” Later I realized that was his way of showing displeasure at tag-along journalists. The next year, after the Medal of Honor ceremony for TUB member Michael Monsoor (whom I’ve written about in many places including, most recently, this publication), we gathered in a bar (three blocks from my Virginia house!) and they were extremely complimentary. I had introduced TUB to the world by going to the most dangerous part of the most dangerous city and actually exiting on two feet. (READ MORE: Veterans and Suicides: It’s Worse Than the VA Reports)

But just barely.

As I said, you have to expose yourself. So in my video from the rooftop with the SEALs you can see me standing with my head over the wall and hear the machine gun bullets whizzing by. What could I do?

But other times I screwed up.

I was filming a guy while standing right next to a huge damned window. And no, I hadn’t brought my Romulan cloaking device. Fortunately, at that time the soldier I was filming had no targets but another one on a different part of the roof, Spec. 4 Rob Killian, had a better view and brought down three guys from there. So I scurried over there. You can see my video in which a sniper took a shot at one of us, probably him, and he was quite animated about it. Spooked then exhilarated. Later I returned to my big window and there was a hole right where I had been standing. Snipers don’t shoot at nothing. He fired that round right as I was moving. Since I didn’t have the side armor plates, Killian quite possibly saved my butt. And the rest of me.

The SEALs, now on a rooftop, take advantage of a break in enemy fire to reload. Note all the shell casings at their feet. These men took out several enemy suicide bomb cars from here, one with that M79 that he handled like a pistol. One shot; one kill. Marc Lee, the first SEAL killed in Iraq, is at the far right. Note the ML on his satchel.

I think it was that same night when I was back in the base camp and was sick and damned tired of slipping and falling on the sand, which had the consistency of talcum powder. (Except when wet, when it’s like walking in peanut butter.) So I saw no harm in cupping my hand over my flashlight to provide just the very narrowest beam so I could see where I was going. Immediately, Crack! The soldier walking with me said calmly, “Fumento, you should probably put that flashlight away.” Done long before he finished that sentence.

Most embarrassing is something I told almost nobody about until now. I was on a rooftop with a squad from the 101st during a night raid with a new camera. I took a picture of them without realizing that in night mode the camera projects a red laser! I was painting them for a sniper! Actually, they need more time than that. But I felt awful.

Most of these events only seem funny in retrospect. Once I was supposed to be embedded for a week at a combat outpost (COP) with troops from an artillery division in Ramadi, which had no showers. One night we went out we had to jump across an irrigation ditch. Everyone else had what’s curiously called a “shroud” on their helmets to mount night vision goggles. It’s a hitch. Mine, alas, did not. K-Mart special, I guess. I couldn’t see the ditch and ended up not on the other side but inside. And it was filled with fertilizer, and not of the type American farmers use. Phew! They found a way for me to go back to the main camp before the week was up.

By the way, the COP commander would relax by playing war video games. I’m thinking, “You do this for a living, why…?” Ah, well.

Deaths are never funny, no matter on what side, but occasionally an injury can be. During an ambush, I was the first American to come upon an Iraqi ally shot right through the nose. Got a picture. And yes, I thought it was funny. Because really he was fine; it was just a piece of shrapnel from a ricochet and if it had been the whole bullet it would have taken off the nose and lot more of the face. I certainly didn’t laugh; I called for a corpsman, one of the Navy medics who accompanied us. (The Navy felt really left out of both wars and did everything they could to get their guys into action.)

Unbelievably, this Iraqi took a ricochet round that went right through his nose. He’s now The Man with Four Nostrils.

Today I do still have some PTSD. Heightened awareness seems pretty standard, as well as missing the most thrilling days of your life. It’s why soldiers who saw horrors a million times worse than anything I did still watch war movies and play war video games. That hyper-reality. And survivor guilt. Never mind that I was as much a volunteer as possible, not just going overseas as a civilian but to the most dangerous places I could get.

When I got to Camp Ramadi outside the city my handler asked where specifically I wanted to embed and I answered in what now seems an embarrassing John Wayne impersonation, “The redder the better!” Various shades of red and green were used on maps to indicate current levels of violence.

Never mind that I was almost killed my first time over and needed 10 surgeries to fix it up. People who looked out for me so I could do my job, including my repeated handler Marine Major Megan McClung and Monsoor, who took up a position behind me when I ran out into the street after shooting broke out, had every bit the right to return home as I did. But they didn’t. Heck, Megan quit her lucrative and relatively safe contractor job just to die when an IED destroyed the Humvee carrying her and two others, making her the highest-ranked female Marine to die in Iraq. I saluted her as she lay in her casket at Arlington Cemetery, as well as in the pages of TAS.

Being startled by sudden sounds, is pretty common too. But the worst sound regards the snipers who were always crawling up my ass. An outgoing round sounds like a tiny little explosion; incoming is a snap. My mortal enemy now is bubble wrap. The snapping of which to some people is more addictive than crack. My first landlady in Colombia found my bubble wrap I used to move there and could not stop pop, pop, popping. “Detengenselo, porfa!” Stop it, please! She didn’t. She couldn’t.

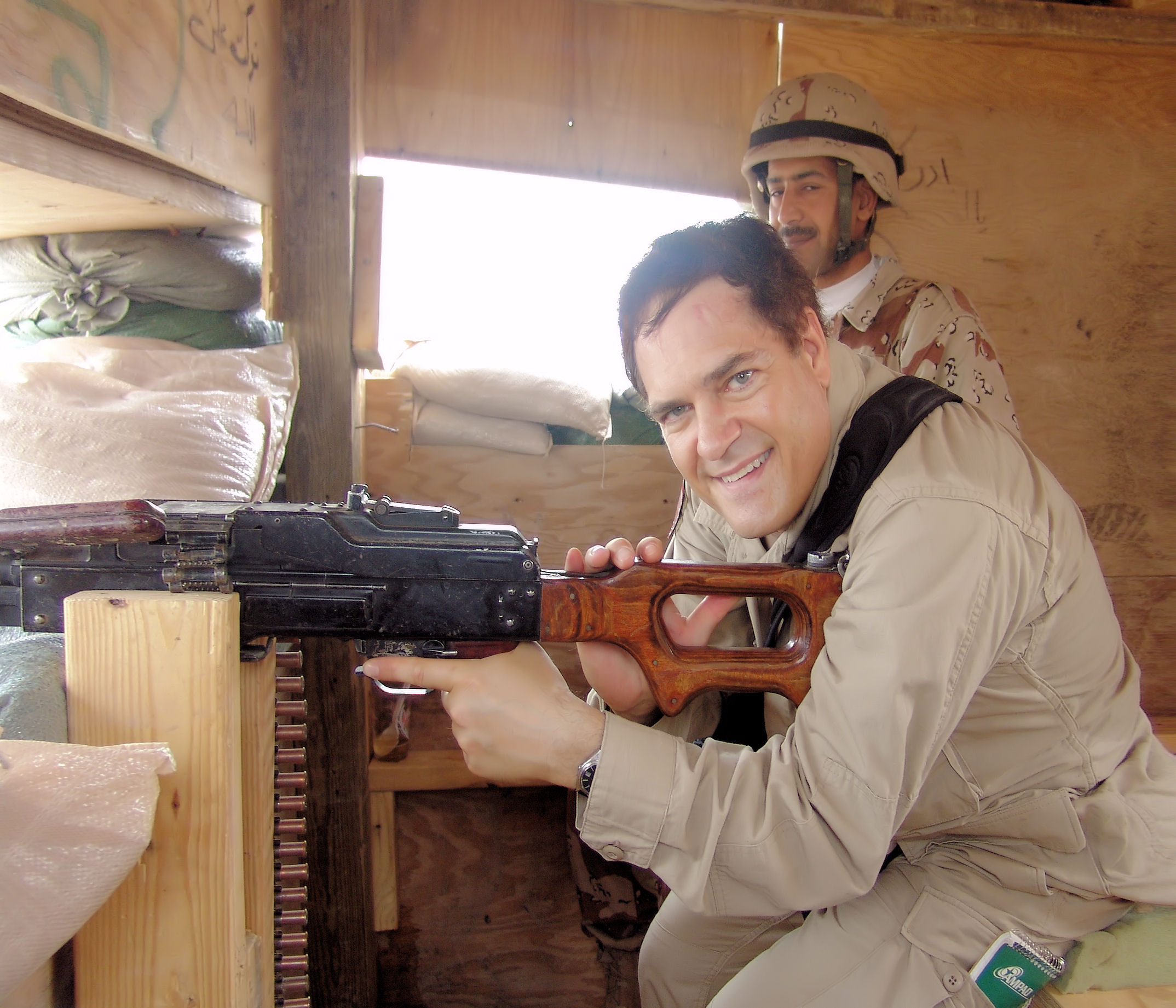

Author handling a Soviet-block light machine gun.

Last year my boss’s daughter snapped something in my ear and I shot her a look almost as deadly as a sniper round. I felt very badly about that! I assure you I have no problem with slamming garage doors and I will never find an AK-47 laying around, enter a post office, and start shooting. But do not under any circumstances pop bubble wrap around me. It could come out badly for both of us.

I hope I’ve given a reminder that every veteran’s story is a mix of valor and vulnerability, and while we may seek to understand through media, the reality is far more complex and deeply personal. It’s a call for openness, support, and a gentle reminder that sometimes, amidst the intensity of war, there are moments of unexpected levity that remind us of the resilience of the human spirit.

Michael Fumento was a sergeant with the 27th Engineer Battalion (Combat)(Airborne) from 1978-82 and an embedded reporter in either Iraq or Afghanistan from 2005-2007.