Editor’s Note: This piece on race and the civil rights movement is the fourth in a series by Speaker Gingrich on American despotism. Listen to The American Spectator’s exclusive interview with the speaker here. Find the rest of the series here.

The great upheaval over race in America began in the 1950s and accelerated dramatically in the 1960s.

In many ways, the bridges that started being built in that era are crashing down around us. Today, we have the Black Lives Matter movement (which has supported widespread destruction across America and grifted many millions of people for misspent donations). Anti-white racism fuels most of the current cultural left. Educational efforts such as the 1619 Project seek to rewrite American history so that slavery and the African American experience are the central themes. There is a growing contempt for police (especially white officers) and acceptance of crime. All of these make up part of the hardcore anti-Americanism emerging as the central value of the left.

READ MORE from Newt Gingrich: American Despotism: How the ’60s and Early ’70s Ignited the Culture Wars

While much of this radical activism and militant anti-Americanism extends beyond the struggle over race, the power of that conflict was the biggest driver of change in the 1960s. The struggle against segregation — both de jure (legal) and de facto — became powerful. In some cases, it was violent and created patterns of thought that became a significant part of the challenge to our constitutional system and the rule of law. Consider how much of today’s radicalism is organized around the struggle against repression and injustice.

However, segregation is only one part of the story. The classic civil rights movement wanted an end to segregation but saw itself as wanting to belong to America. Then, the rise of anti-white and anti-American philosophies and movements dramatically increased tension. These combined with the growth of a parallel white anti-Americanism that sought emotional identity with, and endorsement by, the larger black movement. Finally, the collapse of law enforcement combined with frustration that legal desegregation did not automatically achieve “the promised land” goal. This led to stunning outbursts of violence across the country — including substantial rebellions in the north, which had always treated (and ignored) racial problems as exclusively southern.

The Trigger of the Civil Rights Movement

I was born in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and grew up in U.S. Army schools. When we came to Fort Benning, Georgia, in February 1960, I encountered legal segregation for the first time. The state of Georgia legally enforced separation of blacks and whites. There were separate water fountains, bathrooms, and schools. “Separate but equal” had been the rule since the U.S. Supreme Court endorsed it in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. However, in practice, “separate but equal” meant separate but clearly unequal. White schools and facilities were superior to their black counterparts. Local law enforcement — and, when necessary, the National Guard — enforced black compliance with segregation.

If the state government was not aggressive enough in suppressing and controlling blacks, there were private groups such as the Ku Klux Klan willing and eager to use force to ensure control of the black population. From 1865 to 1950, there were more than 6,500 lynchings of African Americans. Despite efforts to pass federal anti-lynching bills as early as 1922, Southern Democrats used the U.S. Senate filibuster to block them — even when evidence of brutal killings was overwhelming.

In May 1954, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that “separate but equal” was unconstitutional — and that schools could no longer be segregated — it triggered a convulsive struggle across the South and some northern cities (Boston, for example). The black community felt great hope. The racist elements of the white community felt great fear.

More than 100 years earlier, Alexis de Tocqueville suggested that revolutions occur from a period of rising expectations. For many civil rights advocates in 1954, the sense of despair in taking on government-enforced segregation had been replaced by hope. The gradual progress toward integration made during and since World War II could be dramatically accelerated by direct action.

On Aug. 28, 1955, just over a year after the Brown v. Board ruling had offered hope on ending segregation, Emmett Till, a black 14-year-old, was tortured, mutilated, and killed while visiting a small town in Mississippi. He was visiting from Chicago and had reportedly whistled at a white woman. Her husband and his half-brother went to the house where Till was staying, kidnapped him, murdered him, and dropped him in the river. Three days later, his tormented body was found. His mother could only identify him by a ring he wore.

There was controversy when his body was returned to Chicago and his mother insisted on an open casket funeral. She said, “I wanted the world to see what they did to my baby.” The two killers were cleared by an all-white jury. In 1956, since they could not be retried because of the prohibition on double jeopardy, they sold their story to Look magazine and admitted they killed the 14-year-old.

The Start of the Fight Over Race and Equality

Till’s brutal killing — and the reaction to the horrifying open casket — is considered by many the trigger that launched the civil rights movement. People were becoming fed up with oppression and were tired of waiting for freedom. Roughly three months after Till was killed, the Montgomery bus boycott began when Rosa Parks refused to stand up for a white man on the city bus. This was not a spontaneous moment. The organizers had thought through a point of vulnerability and publicity that could leverage real change. Since 75 percent of the riders on the Montgomery bus system were black, a boycott could cripple the system. In fact, on the first day, 90 percent of the African American passengers boycotted the buses. Organized carpools were established, and black taxi drivers agreed to charge the 10 cents that constituted bus fare. (READ MORE from Newt Gingrich: American Despotism: The Historic Roots of the Constitutional Crisis)

Parks volunteered to be arrested for violating the city ordinance that whites had the right to demand seats from blacks. She was a long-time leader as secretary of the Montgomery NAACP. She had led an inquiry into the Sept. 3, 1944, rape of Recy Taylor by six white men. That led to an organized effort to protect black women from white violence.

Of course, transportation boycotts did not originate in Montgomery. The first incident was in 1841, when Frederick Douglass and his friend James N. Buffum refused to leave the white-only car on the Eastern Railroad. Massachusetts was one of the most favorable states for African Americans before the Civil War and had a large abolitionist faction. Douglass’ experience was a factor in passing the Civil Rights Act of 1875. It guaranteed equal access to public transportation for people of all races. Unfortunately, the U.S. Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in 1883. It would be reenacted in large part in the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968. In fact, the 1875 Civil Rights Act was the last one passed under Reconstruction. Only when President Dwight D. Eisenhower supported the Civil Rights Act of 1957 did the process of federal legal protections begin to be taken up by Congress (each time against bitter opposition from segregationist Southern Democrats).

During their planning of the bus boycott, the Montgomery civil rights activists found a brilliant orator and organizer in a young minister, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. He emerged as the leader of the boycott, which lasted from Dec. 5, 1955, to Dec. 20, 1956 (381 days). That year-long struggle galvanized activists across the country and dramatically increased reporting about civil rights issues. As a result of the continuous effort, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Montgomery’s transportation segregation laws were unconstitutional.

The complete victory of the non-violent but organized and patiently determined protest set the stage for a dramatic series of actions. They were paralleled by federal enforcement of the Brown v. Board decision. Eisenhower was cautious but determined to enforce the court’s ruling.

In September 1957, when the Little Rock School Board sought to desegregate, Gov. Orval Faubus was bitterly opposed. When the NAACP picked students who were academically prepared and personally mature enough to deal with the pressures and hostility they would face — they became known as the “Little Rock Nine” — the governor moved to stop them. He called out the Arkansas National Guard and ordered them to block the students from going into the school. The school board opposed the governor’s segregationist stand.

Eisenhower had warned Faubus against trying to block the U.S. Supreme Court decision. He ordered elements of the 101st Airborne to Little Rock and federalized 10,000 Arkansas National Guardsmen under the authority of the Insurrection Act of 1807. The nation watched with fascination as segregation was forced another step forward with a show of military force. The students were admitted but faced aggressive hostility from segregationist students. They stood up to the pressure, but it was tough.

The process of protesting segregation took another step forward on Feb. 1, 1960, when four black college students walked into the Greensboro, North Carolina, Woolworth and sat at the whites-only lunch counter. They were ejected. The following day, more black college students sat at the lunch counter. For five months, three weeks and three days, students sat in at Woolworth gathering national media attention. On March 16, 1960, Eisenhower commented that he was “deeply sympathetic with the efforts of any group to enjoy the rights … of equality that they are guaranteed by the Constitution.”

The sit-ins helped inspire the Freedom Rides of the summer of 1961. Volunteers rode buses throughout the South to challenge white-only facilities. The original 13 riders, beginning on May 4, 1961, included John Lewis, who was severely beaten in Rock Hill, South Carolina. Lewis would go on to again be beaten severely at the Selma bridge. He later became an Atlanta congressman and the Democrat whip in the U.S. House. I worked with him and admired him as a genuine American hero.

Southern segregationists reacted violently against the Freedom Riders, and the Kennedy administration sent 600 U.S. marshalls to Montgomery to protect the riders from an angry white mob. The Kennedy administration was for civil rights, but it was also cautious about taking on Southern Democrats and segregationists too aggressively. The sheer clarity of the conflict ultimately forced it to take sides.

When U.S. Air Force veteran James Meredith was accepted into the segregated University of Mississippi by court order on Sept. 29, 1962, the resistance was deep and violent. President John F. Kennedy was forced to undertake the largest mobilization in the history of the Insurrection Act of 1807. Ultimately, 31,000 troops and marshals imposed order on Oxford, Mississippi. On June 12, 1961, NAACP Secretary for Mississippi Medgar Evers, who had counseled Meredith through the process of enrolling at the university, was murdered outside his home. The killer, Byron De La Beckwith, was a KKK member. Two all-white juries ended with hung juries (Mississippi had blocked blacks from voting in 1890, and so they were not eligible to serve on juries).

Nine days after the trial, on June 21, 1963, three civil rights volunteers were killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi. Their bodies were buried beneath an earthen dam. It took an all-out effort by the FBI, with the help of 400 sailors loaned by the Navy, to find them. The FBI ultimately identified the killers, but the state of Mississippi refused to prosecute them. Ultimately, 18 were tried for civil rights violations, which was a federal crime and could be prosecuted by the federal government. The FBI file was called “Mississippi Burning,” which became the title of a powerful movie about the tragedy. (READ MORE from Newt Gingrich: American Despotism)

In 1966, Meredith would lead a march from Memphis to Jackson to encourage blacks to register to vote after passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. He was shot by a white segregationist, and others came to lead the march while he recovered. On June 26, 1966, Meredith had recovered enough to lead 15,000 marchers into Jackson. It was the largest civil rights demonstration in Mississippi history. Incidentally, Meredith was a deeply committed Republican who ran for office several times and worked briefly for U.S. Sen. Jesse Helms.

Martin Luther King Jr., Race, and the Non-Violent Movement

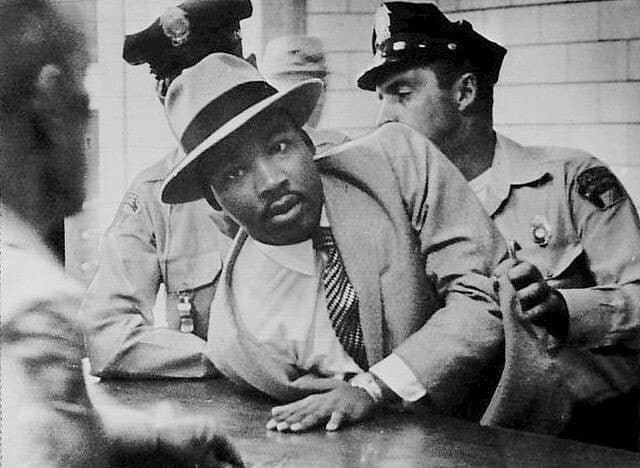

During this same period, King was arrested while leading a protest in Birmingham, Alabama. He was put in a harsh jail and felt challenged when eight white pastors published “A Call for Unity,” which attacked his methods. The white ministers ignored the whole problem of segregation and suggested that the tensions were caused by the protesters rather than the engrained, illegal forces of repression.

King responded by writing one of the most brilliant documents in American history. “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” is worth reading. Published April 16, 1963, it is a compelling definition of what the fight against segregation was about. King wrote:

There can be no gainsaying the fact that racial injustice engulfs this community. Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known. Negroes have experienced grossly unjust treatment in the courts. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in the nation. These are the hard, brutal facts of the case. On the basis of these conditions, Negro leaders sought to negotiate with the city fathers. But the latter consistently refused to engage in good faith negotiation.

King went on to assert:

[W]e have not made a single gain in civil rights without determined legal and nonviolent pressure. Lamentably, it is an historical fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but, as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups tend to be more immoral than individuals.

We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.

This letter has one of the most powerful indictments of segregation as anti-human that was ever written:

But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six year old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five year old son who is asking: “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?”; when you take a cross county drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “colored”; when your first name becomes “nigger,” your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and your wife and mother are never given the respected title “Mrs.”; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness”–then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair. I hope, sirs, you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience.

With perceptive foresight, King warned that if nonviolent protests fail:

The other force is one of bitterness and hatred, and it comes perilously close to advocating violence. It is expressed in the various black nationalist groups that are springing up across the nation, the largest and best known being Elijah Muhammad’s Muslim movement. Nourished by the Negro’s frustration over the continued existence of racial discrimination, this movement is made up of people who have lost faith in America, who have absolutely repudiated Christianity, and who have concluded that the white man is an incorrigible “devil.”

The letter closes with a heart-rending hope for a better future:

Let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away and the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear-drenched communities, and in some not too distant tomorrow the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation with all of their scintillating beauty.

Yours for the cause of Peace and Brotherhood.

King’s letter did not penetrate the heart of hardline segregationists in Birmingham. During mass demonstrations, often involving children, more than 3,000 people were arrested. Bull Connor, the public safety commissioner and longtime Democrat politician, had the police turn fire hoses and police dogs on the crowd — including the children.

The national news media covered the violence against unarmed nonviolent protesters. Several magazines and newspapers published covers with Birmingham policemen and their police dogs attacking children. The rest of America was increasingly fed up with massive resistance from the segregationists — and sympathetic to King and the cause of integration.

King’s message of hope reached its largest audience on Aug. 28, 1963, when more than 250,000 people gathered at the Lincoln Memorial to hear his “I have a Dream” speech. Television stations across the country carried the speech. Its impact was galvanizing for the cause of civil rights. King previewed the key themes three years earlier with a speech on “The Negro and the American Dream,” to the North Carolina NAACP on Sept. 25, 1960:

In a real sense America is essentially a dream—a dream yet unfulfilled. It is the dream of a land where men of all races, colors and creeds will live together as brothers. The substance of the dream is expressed in these sublime words: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” This is the dream. It is a profound, eloquent and unequivocal expression of the dignity and worth of all human personality.

But ever since the founding fathers of our nation dreamed this dream, America has manifested a schizophrenic personality. She has been torn between [two] selves—a self in which she has proudly professed democracy and a self in which she has sadly practiced the antithesis of democracy. Slavery and segregation have been strange paradoxes in a nation founded on the principle that all men are created equal.

Now more than ever before America is challenged to bring her noble dream into reality.… It is a trite yet urgently true observation that if America is to remain a first-class nation it cannot have second-class citizens.

“Letter from the Birmingham Jail” established King as one of the great political thinkers of his time. His earlier speech to the NAACP formed a basis for his core iconic message. With his “I Have a Dream” speech, King reached his most powerful historic appeal. Sixty years later, it is still stunning, touching the heart as well as the mind:

I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right down in Alabama little Black boys and Black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today.

It is important to recognize three key characteristics of King’s messages. First, they seek to fulfill America’s promise and take seriously the Declaration of Independence and the rights guaranteed by the Constitution. Second, they take seriously finding ways to move beyond race and bring people together. Third, they ultimately assume that the American system will respond to nonviolent changes in ways that a dictatorship would not.

Tragically, just 18 days after his great speech, on Sept. 15, 1963, four young black girls were killed in a bombing at the First Baptist Church in Birmingham. The same day, two young black men were killed in the same city. Most Americans were outraged by the violence (Condoleezza Rice is powerful in her description of that experience; she was a young girl in that church).

Two months later, on Nov. 22, 1963, President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. The emotional power of his killing combined with the remarkable legislative skills of President Lyndon B. Johnson created the opportunity to move civil rights legislation that was impossible just a few years earlier. In 1964, 1965, and 1968, major civil rights legislation was passed. With each act, the federal government gained more power to enforce desegregation — even over objections from state and local governments.

Despite the progress in federal legislation, the struggle continued in the Deep South.

The Rising Tide of Civil Rights Violence

From the 1954 Supreme Court decision compelling access to education for all Americans through the 1968 Civil Rights Act, an enormous revolution had taken place. The wrenching effect on the segregationist whites and the determined black activists is hard to overstate.

Importantly, the scale and brutality of violence against those who sought to end segregation further undermined respect for the law. If that is what the American system involved, then many young people decided that the system itself was bad. King tried to bring people together and articulate a positive vision of a unified America. However, the news media exposed the entire country to the brutality and savagery used to subjugate black communities. This undermined respect for the rule of law and the sanctity of authority. When police officers turned dogs and fire hoses on children, Americans developed a real sense that something was profoundly wrong. When juries refused to convict murderers due to racial solidarity, it was hard to speak about justice and the rule of law. (WATCH: Speaker Gingrich Reveals America’s Current Crisis)

In some ways, the culminating event of the civil rights push to end segregation was a series of marches in Alabama. A series of protests in Alabama had been ongoing since January 1965 over efforts to block blacks from registering to vote. More than 3,000 protestors were arrested. To calm things down and focus attention on the issue, three marches were planned from Selma to Montgomery, the state capital. The first march, on March 7, 1965, ended in a disaster on the Edmund Pettus Bridge leaving Selma, Alabama. State and local police attacked the marchers. Many marchers were hurt, and 256 were hospitalized, including John Lewis. The event was described as “Bloody Sunday.”

National anger over the police brutality and the obvious repression of legitimate citizens’ rights led Johnson to address a joint session of Congress on March 15, 1965, calling for a national voting rights law, which was signed into law in August of that year. By the third march, on March 21, 1965, there were federalized Alabama National Guardsmen and United States marshals protecting the marchers. When they reached Montgomery (54 miles away), there was a huge rally with 25,000 people gathering in front of the state capitol. The marchers had won.

The key achievements of the civil rights movement were remarkable. They required a basically decent American people to impose their will on an entrenched minority that was frightened of the future and trying to hold onto a world that was dying. Slavery was followed briefly by Reconstruction, which had offered hope of a more integrated future with legal rights and opportunity for all. Then reactionary white Southern activists imposed segregation as a control mechanism for former slaves — and even for those who were free. A century after the Civil War, a civil rights movement gained the popular support to end the vestiges of legal segregation. However, it did not have the power to end de facto segregation and to address the economic and social effects of 300 years of slavery and nearly 100 years of legal and economic discrimination.

America made progress toward a more integrated future of opportunity for all. But in that context, it came too slowly and unevenly. A hardened minority developed in the African-American community that was determined to take a more militant, anti-white path than the civil rights activists before them.

I’ll look at that phase of history in my next essay.

For more commentary from Newt Gingrich, visit Gingrich360.com.