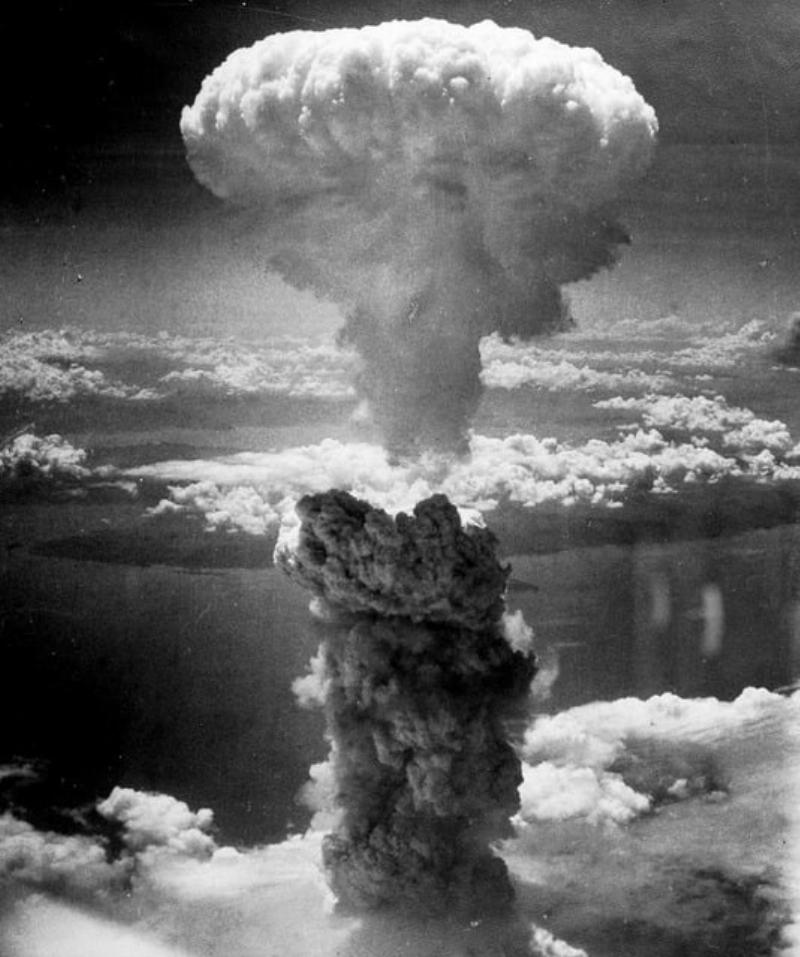

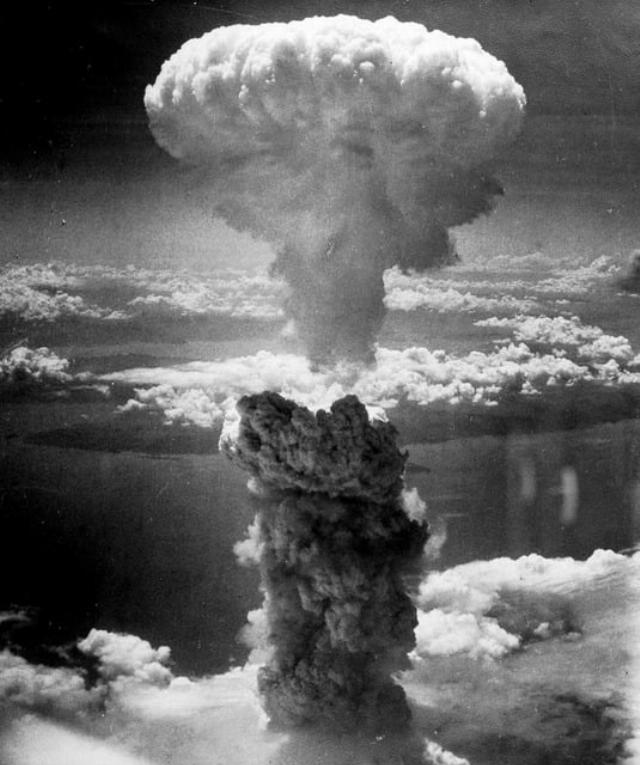

With the passing last week of the 80th anniversary of the U.S. dropping atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima (on August 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (three days later), familiar questions once again arise about our having done so. These include whether it was absolutely necessary in order to bring an end to the war, and whether or not there was any alternative to the two bomb attacks?

Addressing the second question first, an alternative option had been discussed. It involved providing the Japanese with a demonstration by dropping an atomic bomb on an uninhabited island. But such a demonstration involved risks.

As a new weapon of war, the atomic bomb—although it had been tested in the U.S.—raised concerns whether a demonstration might go wrong, resulting in a failed detonation. Such a failure would only embarrass the U.S. and undoubtedly motivate Japanese resolve further not to surrender.

Concerning the second question, the U.S. recognized the Japanese were preparing to defend—at all costs—their island nation against an invasion. They were doing so by activating every able-bodied civilian to fight to the death. The U.S. estimated such Japanese determination would result in at least one million Allied casualties and untold millions of casualties for the Japanese.

Anyone today who doubts the depths of that resolve to continue fighting need only consider how long it took the two last Japanese soldiers—out of hundreds who did so—to surrender.

Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda spent 29 years after the war, until 1974, hiding from the Allies in the jungles of the Philippines, only surrendering when his former commanding officer went there and ordered him to do so. He was followed later that year by Private Teruo Nakamura, who was in Indonesia, and is the last known Japanese soldier to surrender.

With such a strong resolve, President Harry Truman realized the only way to ensure Japan would agree to an unconditional surrender was for its leaders to witness firsthand the bomb’s destructive power. Unknown to the Japanese was just how many of these weapons the U.S. had in its inventory. We had built three, with one already expended in New Mexico to test its viability. Thus, we were left with only two. While a fourth bomb was in the works, the U.S. had to go with what it had. This made it imperative that the two available bombs be used in the most impactful way possible, showing just how devastating they were.

Even after the two bombings, some senior Japanese military officers were still reluctant to surrender. Thus, it was Emperor Hirohito who exercised his authority, agreeing to an unconditional surrender as the reality could not be made any clearer that Japan had lost the war.

While critics of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are quick to point out an estimated 210,000 Japanese lives were lost, they seem to ignore the fact that many more Japanese lives would have been lost had the Allies been required to invade Japan.

Interestingly, long after World War II, some U.S. racial activists—such as Malcolm X—suggested the reason we were willing to drop the bombs on Japan was because they were non-white. However, this ignores the fact construction of the atomic bomb began before Germany’s surrender and was not completed until after its surrender. Up until that time, one bomb was being reserved for it as well.

Just like Germany only surrendered after Hitler was gone, that occurred only because more rational minds prevailed, knowing the war had been lost and that unconditional surrender was the only option. Similarly, the bombs dropped on Japan were a necessary evil to trigger similar rational thinking to come to the fore, spurring leaders to act in the best interests of their people.

Image: Public domain.