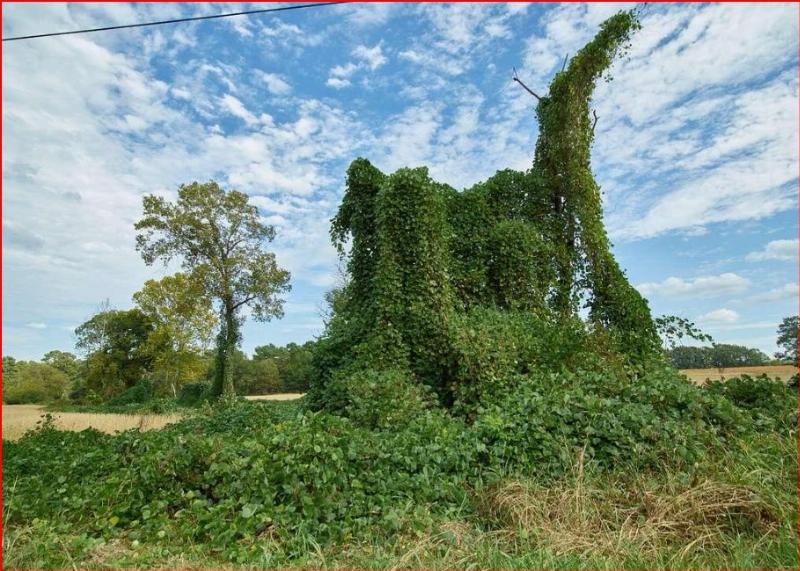

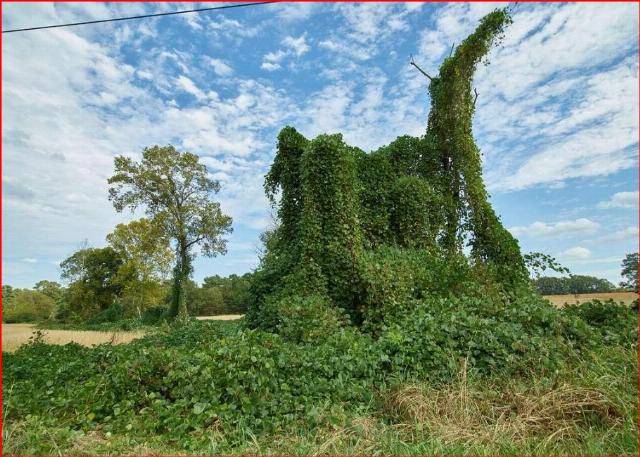

Kudzu is a fast-growing vine introduced to the U.S. from Asia. It was thought that it would serve as fodder for cattle and its rapid growth makes it suitable for controlling erosion.

Unfortunately, it smothers native plants, trees, and structures by outcompeting them for sunlight and resources. It spreads rapidly, covering vast areas and reduces biodiversity by displacing native flora. The USDA estimates that it costs $100–$500 million in damages and control costs in the U.S. It affects agriculture, forestry, and infrastructure, thrives in the southeastern U.S. climates and has no natural predators here, allowing unchecked growth.

Asian carp were introduced to North American waterways as a possible food source for humans, and as a means of controlling algae blooms and some aquatic fauna. These carp outcompete native fish for food (plankton) and space, disrupting aquatic ecosystems. Their rapid reproduction and lack of predators lead to dominance in rivers like the Mississippi. They threaten the $7 billion Great Lakes fisheries by reducing native fish populations. Control measures, like electric barriers, cost tens of millions annually.

Zebra mussels are native to Eastern Europe, and were likely introduced into the Great Lakes through the dumping of water from foreign freighters. They clog waterways, attach themselves to infrastructure, and filter large amounts of plankton, starving native species. They alter water clarity and nutrient cycles, impacting entire aquatic food webs. They cause billions of dollars in damages annually and control costs in the Great Lakes region alone exceed $500 million per year.

Similar stories could be told about the Gypsy Moth, Tree of Heaven, nutria, European Starlings and more. The United States Geological Service even has a database for nonindigenous species.

Most of these species have a few things in common. First, they were introduced into the U.S. either with the best of intentions, albeit with no understanding of the long-term consequences, or through simple negligence. They tend to spread rapidly, outpacing native species and efforts to control them. They disrupt ecosystems by outcompeting native species for resources or altering habitats. They incur high costs due to damage and management efforts, and they tend to lack natural checks such as predators or diseases in their new environments.

Analogous situations are occurring elsewhere, as in European cities such as Malmö, Sweden, or Molenbeek, Belgium where residents are experiencing integration challenges due to large numbers of migrants who do not assimilate. They form insular communities and maintain their own languages and customs. This can lead to cultural richness but also to social segregation. In some cities, this segregation leads to violence. Ireland and Spain, for example are reporting violent clashes between locals and immigrants.

Societies with high levels of unintegrated migration may face difficulties in maintaining shared values or civic participation, though evidence is mixed. For instance, Canada’s multiculturalism model shows successful integration in many cases, while parallel communities in other contexts can strain social cohesion.

Large numbers of migrants can strain public resources like housing, healthcare, or welfare systems, especially if integration is slow. Migrants who do not integrate linguistically or vocationally may face higher unemployment or reliance on low-skill jobs, potentially creating economic burdens.

Host countries spend billions on integration programs (language training, education, etc.). For example, Sweden’s integration costs for recent migrants have been estimated at €1billion – €2 billion annually, although some studies show that immigrants may contribute positively to economies over time.

On the other hand, Swedish Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson said in 2022 that her country has failed to integrate the vast numbers of immigrants it has taken in over the past two decades. This has led to parallel societies and gang violence.

Large-scale migration without assimilation can fuel anti-immigrant sentiments, as seen in the rise of new parties in Europe (e.g., AfD in Germany, National Rally in France) that oppose mass migration.

This reflects public concerns about cultural identity or security. In extreme cases, non-assimilation can lead to parallel legal systems such as informal Sharia councils in some U.K. communities, raising concerns about legal uniformity.

There are countless horror stories of unassimilated migrants clashing with indigenous populations in the U.K. and Western Europe. Locals in a Spanish town recently lashed out after migrants beat an elderly Spanish man.

Members of migrant rape gangs in the U.K. were recently arrested and tried. These rape gangs target British women and girls, who they refer to as "white sluts." Their countrymen protested, calling such arrests racially based.

In the U.S., a 2018 report found that 1 in 5 inmates of federal prisons were illegal aliens, with 91 percent being citizens of Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, Dominican Republic, Colombia or Guatemala.

Both invasive species of plants and animals and large migrant populations can strain resources — ecological (e.g., food, space) for species, and social/economic (e.g., housing, education, jobs) for humans. Invasive species disrupt ecosystems by altering food webs or habitats; non-assimilating migrants may challenge social cohesion or cultural norms, though the extent depends on scale and context.

Controlling invasive species requires costly, ongoing efforts (e.g., kudzu removal). Similarly, integrating large migrant populations demands significant investment in education, language training, and social programs. Invasive species spread quickly due to high reproduction or lack of predators. Large-scale migration can lead to rapid demographic changes, particularly in urban areas, outpacing integration efforts.

The spread of invasive species is biological, while migrants are human beings with intentions, choices and rights. They are often fleeing hardship or seeking opportunity. While ecosystems have limited adaptability to invasive species without external intervention, human societies have laws and policies that can adapt to and even benefit from controlled migration. Migration effects can evolve over time, with many "non-assimilated" groups eventually integrating. The Italian and Irish immigrants in the U.S. are excellent examples.

Similarly, the U.S. is now home to approximately 3 million people from India. Indian immigrants are more likely to be highly educated, to work in management positions, and to have higher incomes. They also have lower poverty rates.

A number of years ago, I had a student from India transfer into my school in April. Her father was bilingual but she only spoke Hindi. She and her mother studied English together for the next five months, and when she started school in September she spoke it perfectly. Linguistic assimilation is possible, if one is willing to work at it. Compared with both the overall U.S.- and other foreign-born populations, Indian immigrants are more likely to be highly educated, live in intact families, work in management positions, and have higher incomes.

Drawing an analogy between invasive species and vast numbers of unassimilated migrants poses real challenges.

They both strain resources, create friction between native and nonnative members and incur management costs.

Invasive species are inherently destructive in ecological terms while the impact of migration depends on scale and policies. Some studies show that second-generation migrants often adopt host-country norms while retaining their own cultural heritage, unlike invasive species which rarely "integrate" into local ecosystems.

Large-scale migration without assimilation obviously strains social and economic systems which can lead to cultural or political tensions.

However, human societies have a greater capacity for adaptation than ecosystems, and migration's long-term effects can be positive.

Comparing invasive species with mass migration can be useful for understanding resource competition and disruption, but it breaks down when we consider human agency and the potential for integration over time. It also runs the very real risk of dehumanizing people who are seeking to improve their lives.

The current situation with illegal immigrants has been developing for decades, and accelerated markedly under pResident (not a typo) Biden's disastrous term in office. While the Trump administration is finally making a real effort to address it, the situation will likely continue to be problematic for years to come.

Image: Library of Congress, via Picryl // public domain