Many of us are counting down the days to the 250th anniversary of our nation’s Declaration of Independence. It’s important to remember that when our Founding Fathers were on the road to independence, they were not sure of the outcome. It’s also important to remember that their road to independence was long and tiring.

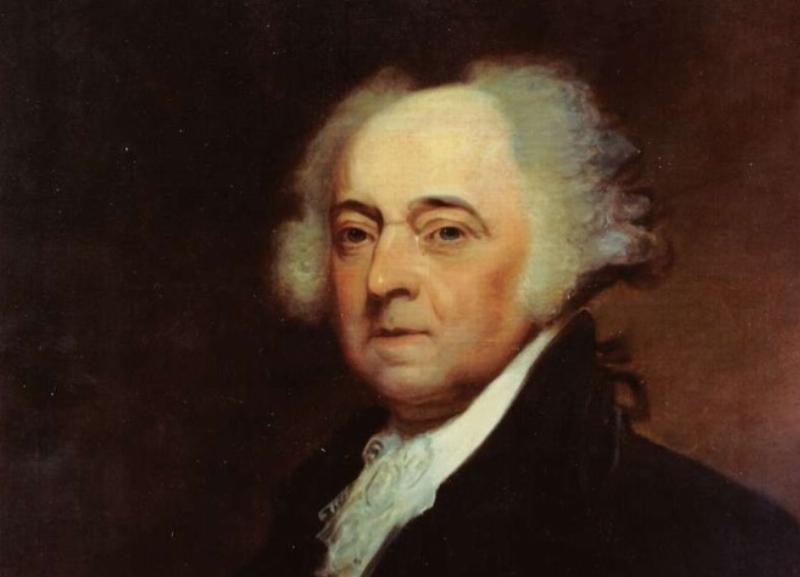

The Battles of Lexington and Concord happened in April, 250 years ago, a few miles west of Boston. Shortly after the battles, John Adams, a member of the Continental Congress who lived near the battleground with his wife, Abigail, and their children, rode through the town, talking to some of the people who had been involved in or had witnessed the confrontations. For him, this conflict with the British was personal. He understood the price that the patriots could pay if they were to lose: death for treason.

Not long after, Adams left his wife and children at their farm south of Boston and traveled to Philadelphia to attend the Second Continental Congress.

Upon arriving, John wrote Abigail on May 8, 1775:

Our Prospect of a Union of the Colonies, is promising indeed. Never was there such a Spirit. Yet I feel anxious, because, there is always more Smoke than Fire—more Noise than Musick. Our Province is nowhere blamed. The Accounts of the Battle are exaggerated in our favour.—My Love to all. I pray for you all, and hope to be prayed for. Certainly, There is a Providence—certainly, We must depend upon Providence or We fail.

He knew that the time was right for the colonies to band together, but he also knew that success was not guaranteed. He looked toward God for intervention and guidance.

The Second Continental Congress got underway on May 10, 1775. The attendees — representatives from the 13 colonies — had been given a range of instructions from their respective home states.

Some, including New Englanders John Hancock and Samuel Adams (a second cousin to John), exhibited zeal for independence. Others were part of the cool faction, including John Dickinson from Pennsylvania, who led a move by the Congress to petition King George III for peace — the Olive Branch Petition, which was dismissed.

A little over a month after the Congress convened, John Adams nominated, and Samuel Adams seconded, George Washington to command the revolutionary troops as general.

Whereas Dickinson clung to the hope of reconciliation, Adams and others increasingly believed that the only way forward was through a declaration of independence.

Throughout the meetings of the Continental Congress, John Adams served on 90 different committees, chairing 20 of them. These committees included the naval committee; the board of war; and the Committee of Five, which drafted the Declaration of Independence. In that committee, Adams worked alongside other Founding Fathers, including Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston.

Although Jefferson was the declaration’s primary author, Adams played a crucial role in advocating for Jefferson to write the document and strongly defending it on the floor of the Congress.

On July 1, 1776, the Congress debated the Declaration of Independence. Dickinson argued adamantly against it. He knew he had become unpopular and thought his opposition could end his career, but he warned that to move forward with the Declaration of Independence would be to “brave the storm in a skiff made of paper.”

After delivering his remarks, Dickinson retired to his seat, and a storm could be heard battering the windows. For a while, no one rose to defend the declaration. Finally, John Adams took it upon himself to provide his argument for freedom.

“No transcription was made, no notes were kept,” wrote David McCullough in his biography John Adams. “There would be only Adams’s own recollections, plus those of several others who would remember more the force of Adams himself than any particular thing he said. ... That it was the powerful most important speech heard in the Congress since it first convened, and the greatest speech of Adams’s life, there is no question.”

Jefferson recalled later that Adams’s conveyed his speech “with a power of thought and expression that moved us from our seats.”

Richard Stockton, a delegate from New York, wrote that Adams was “the man to whom the country is most indebted for the great measure of Independency. ... He it was who sustained the debate, and by the force of his reasoning demonstrated not only the justice, but the expediency of the measure.”

Adams’s strong arguments for freedom could not have been envisioned 250 years ago, a little over a year before we declared our freedom. It was the painstaking work done daily in the Second Continental Congress that made possible the writing of the declaration, the defending of the declaration, and the adoption of the declaration.

As with all history, in retrospect, what occurred may seem inevitable. But just imagine what you might have thought 250 years ago had you been attending the Second Continental Congress as it was convening. At the time, no one in attendance was able to offer a clear vision of what it would lead to: our freedom as a nation.

Jackie Cushman is the president of the Adams Memorial Commission.

Image via Picryl.