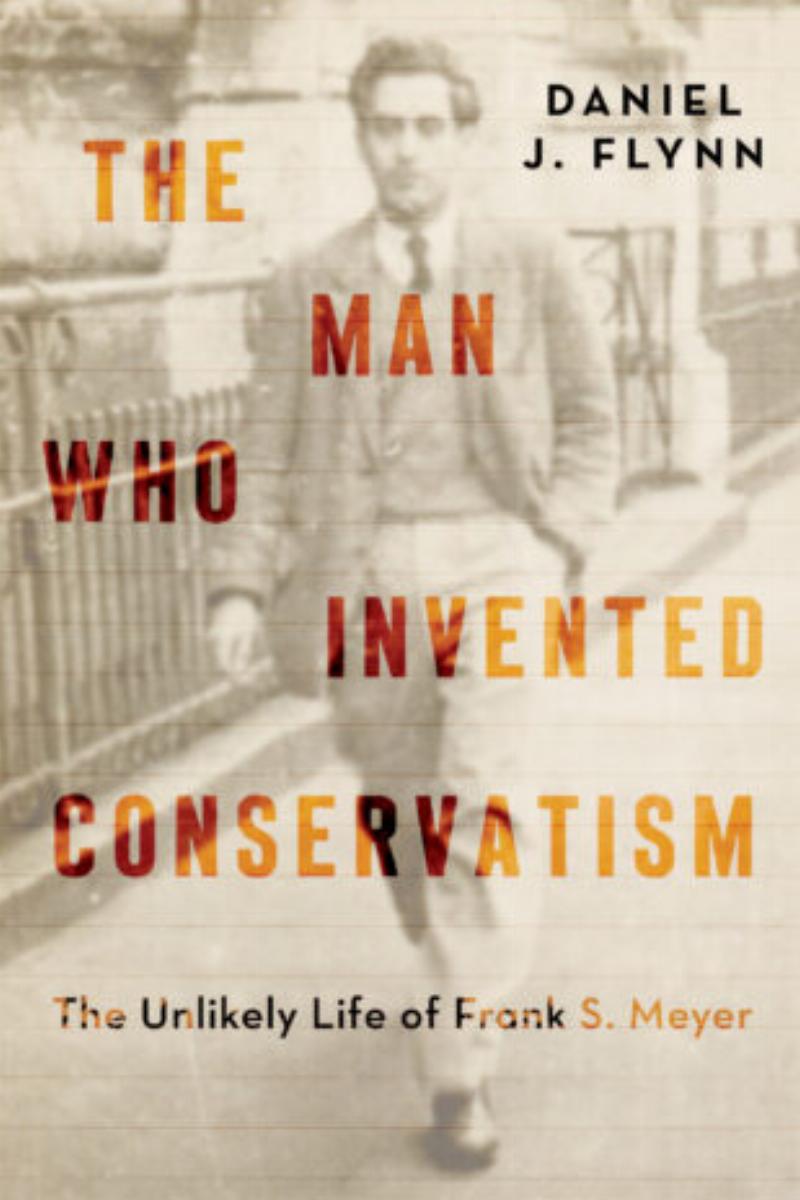

President Harry Truman famously said, “The only thing new in the world is the history you don’t know.” Daniel J. Flynn’s latest tome, “The Man Who Invented Conservatism: The Unlikely Life of Frank S. Meyer”, fits that bill. Flynn, a senior editor at The American Spectator, examines the ideological evolution of one of conservatism’s most paradoxical and overlooked architects, Frank S. Meyer.

Image: Public domain.

Flynn draws from archival materials that include letters, documents, and personal artifacts to uncover new perspectives on Meyer’s intellectual journey and lifelong relationships. This long-lost treasure trove of history was rediscovered three years ago, anchoring Flynn for three days as he sifted through the chronological gold mine hidden within a former soda warehouse in Altoona, Pennsylvania.

With exhaustive research and vivid storytelling, Flynn chronicles Meyer’s improbable political legacy from Marxist demagogue to conservative academic. Among the pantheon of conservative American thinkers that stretch from John Adams to Thomas Sowell, it is Meyer who emerges as the godfather of the American conservative movement.

Flynn paints a rich, nuanced portrait of Meyer, revealing the intellectual rivalries, friendships, and ideological battles that shaped the contemporary post-World War II conservative crusade with Meyer at its philosophical core.

Meyer was an intellectual and political acrobat, and central to his legacy was his development of “fusionism,” that reconciled libertarianism and traditionalism. It was fusionism that influenced the Goldwater coalition, which bequeathed Ronald Reagan his philosophical scaffolding, offering an avenue for free-market evangelists and moral crusaders to harmonize.

Meyer’s contradictions and convictions defined the ideological contours of modern American conservatism. Complex lives sculpt and influence political legacies as Meyer’s fusionist thought continues to echo, fracture, and evolve in today’s ongoing political discourse.

Meyer was an atheist who sympathized with Catholic thought, a libertarian who valued tradition, and a radical who ultimately embraced restraint. These contradictions are not smoothed over; they are presented as essential to understanding Meyer’s intellectual depth.

His paradoxes reveal a disheveled, deeply human ideologue. He saw liberty and tradition not as enemies, but as necessary counterweights. Meyer argued liberty was the highest political good, but only when exercised within a framework of virtue, understanding that political movements are built not on purity, but on persuasion.

Meyer was more than a theorist, editor, and mentor, but a cultural force in the first degree. Academic pursuits at Princeton and Oxford led to his role as a founding editor of National Review, where he wrote the longstanding and weighty column “Principles and Heresies.”

His personal life is woven throughout the narrative reinforcing how belief systems are lived as much as they are theorized. The Cold War backdrop adds another layer to his intellectual fabric underscoring how anti-communism served as both a catalyst and crucible for Meyer’s eventual conversion.

Flynn’s prose blends scholarly rigor with narrative flair that transcends the conventional biography by breathing life into Meyer, long relegated to the margins of historical irrelevance. Flynn reconstructs Meyer’s journey as both theatrically charged and ideologically complex, crafting a storyline that makes convoluted ideological shifts feel personal and accessible while reading like a novel.

The sheer scope of Flynn’s research — 129 pages of acknowledgements, bibliography, and index, attests to the depth of the author’s excavation and underscores Meyer’s evolution not as a clean ideological pivot, but as a layered metamorphosis. Meyer emerges as a paradoxical academic perched at the anxious intersection of Cold War conservatism.

Flynn’s treatment of Meyer evokes the Thomistic balance of charity and clarity. He probes Meyer’s contradictions not to dismiss them, but to illuminate the restless intellect of a man who believed, like Thomas Aquinas, that truth is not merely known, it is lived.

The result is a well-researched and revealing portrait of a scholar whose ideas remain relevant.

In an era where ideological nuance is treated like betrayal, Meyer’s life reminds us that contradiction is not a weakness, but the price of finding truth.

Meyer’s conviction that ideas shape history is not as abstraction but a vocation with Flynn guiding readers through a life marked by philosophical and moral rigor.

For those who possess a reading list that is drawn to narrative history and biographies, Meyer’s story needs to be at the top of the list.

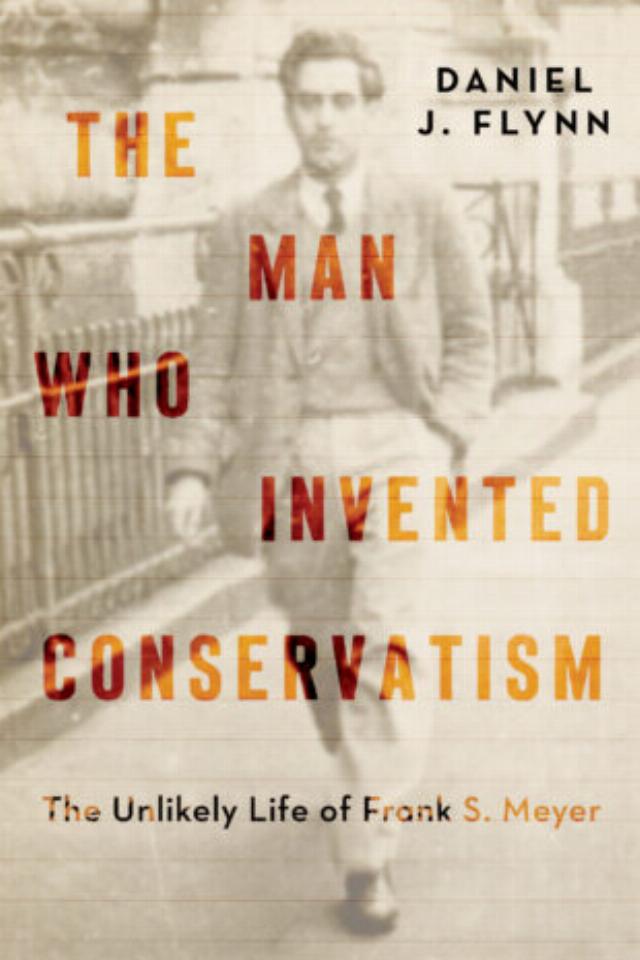

Image: Book cover.