Last week, a D.C. District Court judge, James Boasberg, took it upon himself to substitute his feelings for the President’s statutory authority under the Alien Enemies Act (“AEA”). When issuing his order telling the President to return to the U.S. planes filled with Tren de Aragua members bound for Venezuela, Boasberg didn’t even attempt to find law to justify his decision.

Today, the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit backed Judge Boasberg. A quick read shows that its reason for doing so is utterly spurious because it glosses over the fact that the courts lack any jurisdiction in this matter.

The court begins by explaining that the AEA is one of a trio of laws that marked a fight between Federalists and Jefferson’s Republicans. It implies that the AEA should be considered as dead as the others in the trio, which are long since gone.

The court also acknowledges that there are conditions that must be met for the AEA to apply: Either there must be a declared war, or there must be a predatory invasion by a foreign nation accompanied by a presidential proclamation of that event. The court concedes that the “AEA vests in the President near-blanket authority to detain and deport any noncitizen whose affiliation traces to the belligerent state,” providing that the U.S. is at war or suffering an invasion or predatory incursion. The rest of the opinion justifies the Court’s authority to make this decision.

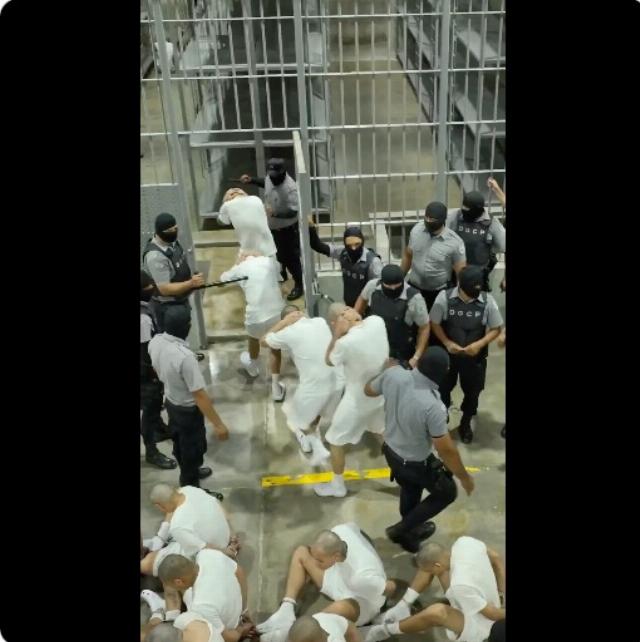

On March 15, Trump invoked the AEA, contending that Tren de Aragua, a designated terrorist organization, invaded at the behest of the Venezuelan government, and he began mass deportations of these Venezuelan foot soldiers.

According to the appellate court, it has jurisdiction to hear the matter. It reaches this conclusion not by discussing its jurisdiction under the AEA, which should be a predicate matter, but by discussing general principles applicable to temporary restraining orders (“TRO”).

From there, the court swings into the usual TRO analysis, which is (1) the likelihood of success on the merits, the relative harm to the applicant, (2) the defendant based on granting or not granting the stay, and (3) the public interest.

The meat of the decision is that the government argued that the courts have no jurisdiction to review presidential decisions under the AEA. This is the correct argument. As discussed in detail here, the statute as written—and as interpreted since 1799—says that the only opinion that matters under the AEA is the president’s. The courts have no jurisdiction at all in the matter. Or, as the Supreme Court said in 1948’s Ludecke v. Watkins, the last comprehensive analysis,

The very nature of the President's power to order the removal of all enemy aliens rejects the notion that courts may pass judgment upon the exercise of his discretion. [Fn. omitted.] This view was expressed by Mr. Justice Iredell shortly after the Act was passed, Case of Fries [citation], and every judge before whom the question has since come has held that the statute barred judicial review.

Significantly, in Case of Fries, decided one year after the AEA’s passage and by the very generation that ratified the Constitution, acknowledged that “Such great war powers may be abused, no doubt, but that is a bad reason for having judges supervise their exercise...” This makes sense because the Constitution grants to the president, who is accountable to voters every four years, authority for decisions about conducting war and national security matters. The courts, which do not have to answer to voters, have no constitutional role in these decisions.

Rather than admit that it has no jurisdiction (and nor did Judge Boasberg), the appellate court does what all leftist judges do (Justice Ginsburg was the master of this), which is to create a cascade of case citations, none of which are on point. In this case, the court generally explains why federal courts have jurisdiction over matters involving foreign countries while ignoring their complete lack of jurisdiction under the AEA. The appellate court doesn’t bother to challenge Ludecke (it can’t) but cites a bevy of state or lower court cases or unrelated Supreme Court cases.

The appellate court eventually reached Ludecke only to explain that Ludecke stands for the principle that whether a war has ended is “a political act.” The D.C. appellate court then contends that Ludecke explicitly gives the court the right to review the AEA for “questions of interpretation and constitutionality.”

This deliberately misinterprets Ludecke. Here’s the entire context:

As Congress explicitly recognized in the recent Administrative Procedure Act, some statutes "preclude judicial review." Act of June 11, 1946,§ 10, 60 Stat. 237, 243. Barring questions of interpretation and constitutionality, the Alien Enemy Act of 1798 is such a statute. Its terms, purpose, and construction leave no doubt.

In other words, there are no questions of interpretation and constitutionality in the AEA. Instead, everything about it makes plain that, as the Supreme Court concluded (see above), the statute vests all authority in the president, with no room remaining for judicial oversight. Even Chief Justice Marshall, writing in 1814’s Brown v. United States, acknowledged, “The act concerning alien enemies, which confers on the president very great discretionary powers respecting their persons appears to me to be as unlimited as the legislature could make it.”

All the other questions—that is, when is a war not a war?—while it considered them, the Ludecke Supreme Court rejected because the power under the AEA lies not with the courts but with the executive. Indeed, the Ludecke court explicitly stated that, regarding whether a war is in progress, “These are matters of political judgment for which judges have neither technical competence nor official responsibility.”

It’s only by deliberately misinterpreting the Supreme Court that the appellate court gave itself permission to wade into a matter that is reserved solely for the executive. From that point forward, the appellate court felt free to wade into answering for itself the question of “when is a war not a war” and to determine that it, not the president, has the authority to determine whether a foreign power is invading the U.S. either through an official declaration or through a stealth infiltration.

Everything the court writes is invalid and deserves to be slapped down hard by the current Supreme Court—assuming, of course, that the Supreme Court has any interest in protecting the federal judiciary’s reputation as a vehicle of law and justice, not politics.