I currently volunteer a couple of days a week as a tutor for the STEM program at a local community college. I’ve also recently taken some HVAC courses.

As one of the older folks on campus, I ask questions and mostly listen, and I find students’ perspectives on AI fascinating, varied, and perhaps naive. A few admit to being active users, but the majority don’t seem to use it or even know much about it. Others are firmly against it, citing accuracy issues. Even the instructors often shake their heads, showing little confidence in it and viewing it more as a frustration they have to deal with because of students who don’t do their own work.

It’s striking to me that those on the degree track don’t seem to view AI as a replacement for what they’re working toward. They seem to associate it primarily with the replacement of blue-collar jobs — perhaps because, historically, automation first displaced farmers during the Industrial Revolution and later factory workers performing repetitive tasks.

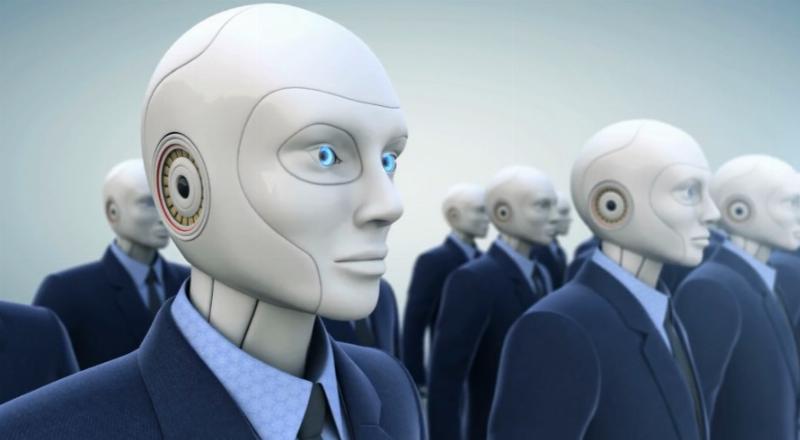

But this next tidal wave of technological disruption will not be another phase of eliminating blue-collar labor; we are now in the early stages of automating and displacing an enormous range of white-collar professions, as AI server farms can perform complex cognitive tasks at scale.

This means many college-educated positions are already replaceable, and humans will become increasingly unemployable in roles once thought secure — except for those involving manual skills in the physical world.

In other words, many of the students taking vocational courses as part of a trade are safe — at least for now.

To fully appreciate this, we need a simpler view of today’s economy.

In basic terms, jobs fall into two primary categories: those in the physical world and those in the digital world.

Physical-world tasks typically require prehensile thumbs, while digital-world tasks generally do not — aside from frequently hitting the space bar on a keyboard.

In the information and digital world, AI can simultaneously handle hundreds of thousands of diverse tasks for people across the globe — assisting with trusts and legal strategies, writing reports, building strategic plans and position descriptions, coding websites, writing scripts, creating videos and even full-length movies, designing health plans and providing health assessments, proofreading and editing documents, generating meeting minutes, preparing briefings, engaging in theological discussions — and on and on.

This capability already exists in server farms and continues to improve rapidly.

However, if your thumb is needed, a remote AI farm can’t perform the job. The physical world can’t be virtualized or outsourced to a remote location — it requires human presence at the source.

For example, an HVAC system can be assessed remotely, but aside from software or firmware updates, it can’t be repaired remotely. There’s no way to replace a busted fan or add coolant from afar.

The same is true in much of the medical field when providing direct care to patients. A remote AI server farm might be able to determine that thirty patients at different locations around the world need IVs due to dehydration, but a medical professional is required at each location to start the IV.

These physical-world actions operate under the constraints of space and time. There is no conceivable way to build a robot capable of instantaneously installing thousands of condenser fans, whether the units are separated by thousands of miles or clustered together.

The same is true for pouring concrete, framing a house, laying tile, wiring a home, installing plumbing, painting walls, roofing a building, or paving a road. Each of these blue-collar tasks requires physical presence, manual dexterity, and the ability to adapt to unpredictable real-world conditions — something no human, no remote AI, or even an advanced robot can replicate at the scale achievable for digital-world tasks.

The same goes for highly skilled fields like surgery. Surgery requires prehensile thumbs and must take place in the real world. No human, no AI, no robot, and no single physical system can perform surgery remotely on millions of people simultaneously. This is not data crunching—there must be a local presence in the physical world. The same is not true for general practitioners, however — they are replaceable.

Why? Because AI can analyze lab results, draw from the collective medical knowledge of the entire world, tailor it to the history of the individual, and compare the data with millions of others in the same cohort. If there’s an issue, AI can then explain treatment options and risks, answer questions, and even schedule medical procedures or surgeries if needed.

Oh, the irony! After centuries of agrarian societies, people left the farms for the cities as part of the Industrial Revolution.

We then automated many manufacturing jobs and shifted to a service-based economy.

In the meantime, we handed out degrees like candy — extremely expensive candy — in the enlightened Information Age.

Now we’ve come full circle: even highly degreed, college-educated individuals may find themselves unemployed and unemployable in the digital world, replaced by a new kind of farm — a silicon-based server farm.

And they don’t seem to see the harvest of this server farm coming for them.

Raymond Morace worked as a civilian supporting the United States Army for over 30 years and, since retiring, has focused on volunteer service in his community. A devoted family man, he and his patient, loving wife have raised five children and now enjoy over a dozen grandchildren. An avid traveler, cyclist, and Ironman competitor, Raymond brings the same dedication and curiosity to his writing, hoping to encourage thoughtful dialogue and reflection.