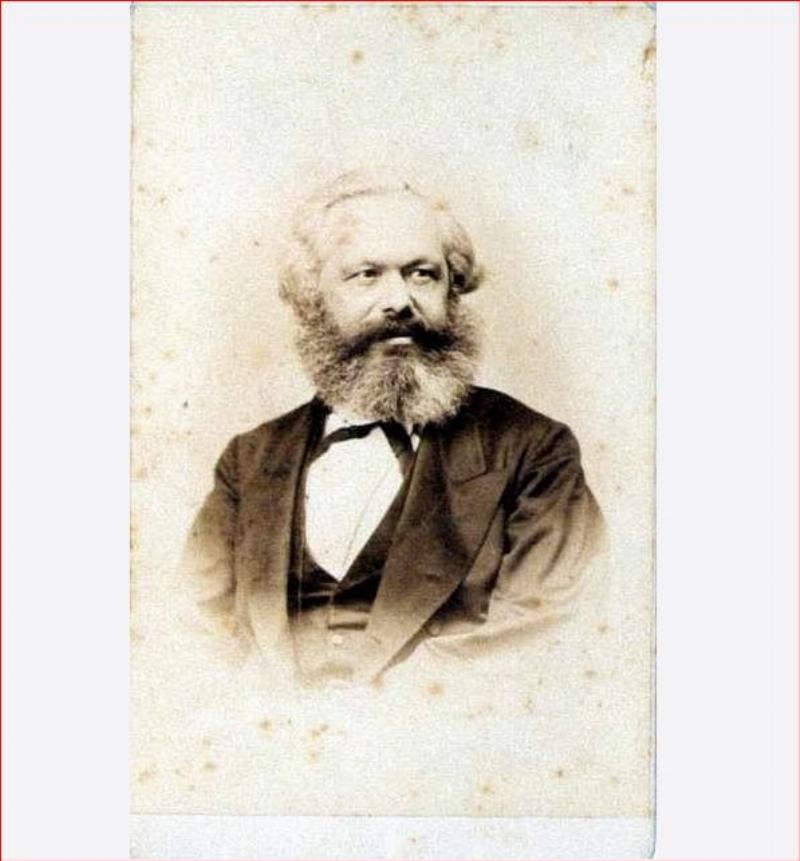

Karl Marx described a world of two main classes: those who owned the means of production (the bourgeoisie), and those who sold their labor to survive (the proletariat). His vision reflected the industrial world of the 19th century—factories, landlords, and mass labor.

Today, we live in a world of startups, social media, and digital nomads. It might seem like 'class' is obsolete. But when we peel back the layers, we find that class, as he saw it, never disappeared — it just changed form.

So what counts as ownership today?

In Marx's time, ownership meant factories, land, and physical infrastructure.

Today, it's code, platforms, patents, and data. The owners are no longer factory tycoons; they are tech moguls.

Companies like Google, Amazon, and Meta don't just sell products — they own the channels through which digital life flows.

These platforms are the modern means of production. If you want to reach customers, communicate, work, or learn, you often do it through their systems.

This control gives them immense leverage. They extract fees, set rules, harvest data, and shape behavior — not just through economics, but through algorithmic influence. They don't just benefit from the market — they define it.

It’s true that anyone can start a business today.

Anyone can code, freelance, or build an audience. And some people do rise: Elon Musk, Sam Altman, and others began with modest means and built empires. But these are rare stories.

Most founders fail. Most people lack the capital, networks, and insulation to survive repeated failure. Success often comes not from a single stroke of genius but from persistence, timing, and the ability to fail safely.

In other words, the field may appear open, but it isn’t level. A few make it. Many don’t. And even among those who “succeed,” control often passes to the investors and platform owners behind the curtain. The modern ladder still exists — but it’s taller, slipperier, and guarded by gatekeepers with venture capital.

If Marx's class model still applies, how do we translate it to today?

The modern worker has more flexibility, but often less security. Gig workers can set their hours, but they’re governed by opaque algorithms.

A freelance designer can work for clients worldwide, but lacks health insurance or legal protection. Even highly skilled tech employees may face burnout, layoffs, and constant performance tracking.

We call it freedom, but it often feels like fragmentation. Workers are disconnected, competitive, and disposable. Unions are rare in tech. Contracts are short term. Protections are weak. The proletariat hasn’t disappeared — it’s been digitized.

The so-called “tech middle class” is also precarious. Product managers, engineers, creators, and micro-founders may enjoy moments of stability, but their position is fragile. They rely on platforms they don’t control. A change in TikTok’s algorithm, YouTube’s payout structure, or Apple’s App store policy can cut off their revenue overnight.

Like the petty bourgeoisie of old — shopkeepers, artisans, and traders — they live between two forces: monopolistic capital above them, and desperate labor below them. They aspire to climb, but often fear falling.

So, what separates today from Marx’s time?

Mostly the aesthetics. Instead of smokestacks and tenements, we have coworking spaces and remote work. Instead of foremen and shift bells, we have dashboards and Slack notifications. But power still flows toward ownership. Profit still depends on control. And inequality — though now dressed in tech jargon — is still a structural feature.

The conflict hasn't vanished. It's just harder to see. We’re no longer marching on factory floors. We’re negotiating rates on Upwork, battling for reach on Instagram, and hoping for funding from investors. The language is new. The struggle is not.

So was Marx right?

Perhaps on his initial analysis. He couldn’t foresee the internet, social media, or SaaS. But he understood something timeless: when a small group owns the tools of production—whether they’re factories or platforms — they will shape the world in their favor.

No, we don’t need to embrace communism to admit this. But we should be honest about how capitalism concentrates power. And if we value real opportunity, we should focus less on hustle culture and more on who owns the digital infrastructure we all depend on.

Class isn’t about who’s rich and who’s not. It’s about who controls the systems. Most of us still don’t. Until we do, Marx isn’t irrelevant — he’s just updated.

Thien Ooi is an engineer who works in the tech field.

Image: Wikimedia Commons, via Picryl // public domain