In most democracies, a legislative speaker in power for more than three decades would be an anomaly, if not a scandal. In Lebanon, Nabih Berri’s uninterrupted rule over parliament since 1992 is treated as political furniture—imposing, immovable, and ultimately untouchable. Now aged 87, Berri is more than a political survivor; he is a symbol of the entrenched, unaccountable elite that has overseen Lebanon’s descent into economic ruin, institutional collapse, and international irrelevance.

A lawyer by training and a warlord by origin, Berri rose to prominence during Lebanon’s civil war as head of the Shiite Amal Movement (“Amal”). Though originally a rival to Hezbollah, Berri long ago cemented an alliance with the Iran-backed group, together forming Lebanon’s dominant Shiite bloc. If Hezbollah is the muscle, Amal is the mechanism—the party that manages the state from within, ensuring that key ministries and public contracts remain within loyalist hands.

Today, the two Shiite factions divide influence over Lebanon’s state and society. Amal dominates the state bureaucracy; Hezbollah holds the weapons.

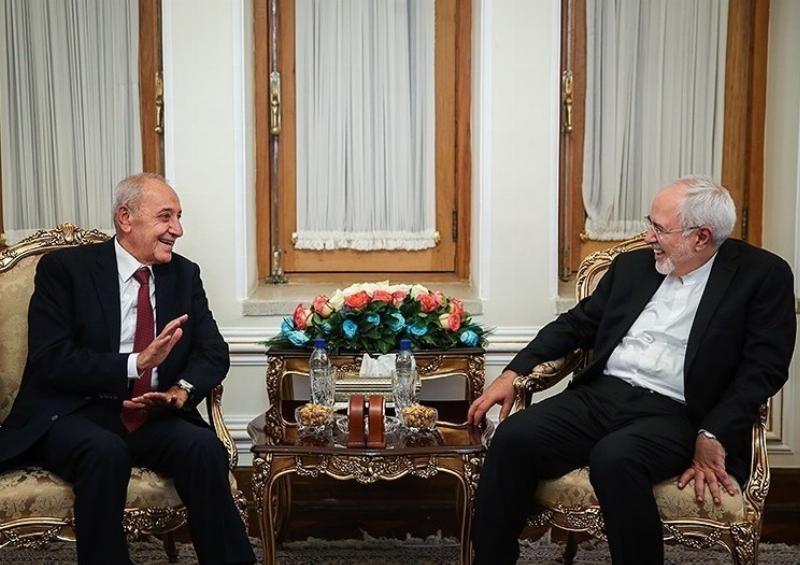

Berri (left) meeting with Iran’s foreign minister in 2017 by Tasnim News Agency. CC BY 4.0.

Though Amal claims to be secular and nationalist, Berri’s politics are anything but. For decades, he has cultivated a base in southern Lebanon and the Bekaa Valley, where loyalty is rewarded with public sector jobs and government contracts.

It is within this nexus of state control and political patronage that Berri and his family have prospered. This patronage machine extends beyond politics. His wife, Randa Berri, has long been accused of exploiting public institutions for personal gain, notably within education and health programs. Activists have alleged that she exerts undue control over NGOs and international aid projects in the south, where Amal’s networks are strongest. Critics accuse her of turning public institutions—especially those related to education and social programs—into fiefdoms of personal enrichment.

Oversight is nonexistent; transparency, irrelevant. The Berri family’s alleged involvement in skimming public funds and monopolizing local development projects has been a common theme in Lebanon’s media and protest slogans. Transparency, needless to say, is not a family value.

More quietly, Berri’s extended family has also thrived under his shadow. Ayman Zakaria Jomaa, a telecommunications entrepreneur married to Berri’s daughter, Maysaa, is emblematic of Lebanon’s oligarchic elite: politically connected, economically mobile, and remarkably insulated from accountability. This year, Jomaa and his brother Imad Jomaa—the latter allegedly involved in several questionable business deals in Iraq, according to an Iraqi government source—were part of the Lebanese delegation to the SelectUSA 2025 Investment Summit in the United States.

Before traveling to the summit, the U.S. Embassy in Beirut hosted the delegation, publicly honoring them as part of its push to boost American investment ties. For many Lebanese watching from a collapsing economy, the optics were enraging. Here were relatives of one of the most powerful—and reviled—political figures in the country, receiving diplomatic courtesies from Washington while Lebanon’s own state institutions remain gutted by the corruption their families helped institutionalize.

But behind the scenes, that tolerance may be fraying. According to a U.S. government source, officials in Washington increasingly view Berri’s unwavering alliance with Hezbollah as a serious impediment to Lebanon’s recovery. With frustration mounting, the Trump administration is now considering targeted sanctions—not only against Berri himself, but also against his family members and closest associates, whose entrenchment in public institutions and business networks is seen as central to the country’s entrenched dysfunction.

The irony is hard to miss. While Berri has consistently resisted U.S.-backed reforms, obstructed IMF negotiations, and aligned himself with Iran and Hezbollah, his inner circle can still gain access to American prestige events and soft diplomatic platforms. For critics, it’s another example of Western double standards in the region: condemning corruption on paper while empowering its beneficiaries in practice.

Though Berri presents himself as a centrist broker—between Christians and Muslims, Sunnis and Shiites, East and West—his record tells a different story. He has consistently resisted any American-led initiative in Lebanon, from political reform to military aid conditioning. In fact, his loyalty has long tilted toward Tehran. During times of regional tension, Berri has reliably aligned himself with Iran’s strategic calculus, echoing Hezbollah’s rhetoric and shielding its political interests.

He has rarely, if ever, condemned Hezbollah’s unilateral wars or its defiance of state authority. When Israel and Hezbollah traded fire in 2024, Berri played the role of mediator only after the fighting paused—careful never to criticize his partner’s recklessness.

Domestically, Berri’s reign has brought paralysis. Parliament under his leadership has become a mausoleum, convened only when his interests or those of his allies are at stake. Key reforms demanded by international lenders—such as restructuring the banking sector or curbing clientelism—have been shelved, watered down, or sabotaged.

He has used procedural games and informal “consensus” rules to block votes, bury legislation, and kill off investigations. His role in preventing the election of a new president between 2022 and 2024 was emblematic: Berri simply refused to call voting sessions until he could dictate the outcome.

For all his maneuvering, Berri commands little legitimacy outside his shrinking base. Among Lebanese youth, especially those who led the 2019 uprising, he is reviled. “All of them means all of them,” the protesters chanted, but Berri was often singled out with special venom. The streets of Beirut have long been defaced with graffiti reading “Berri = Thief.” And yet, he endures.

Part of the reason is the system itself. Lebanon’s sectarian power-sharing arrangement grants the speakership exclusively to a Shiite, and Amal, by historical inertia and brute force, has monopolized that role. But part of the reason is also international. Western and Arab diplomats, reluctant to provoke Hezbollah, have often tolerated Berri as the “acceptable” Shiite—forgetting, or ignoring, that his power depends on preserving the very dysfunction they hope to overcome.

Though Berri styles himself as a political balancer—bridging sectarian divides and mediating during crises—his legacy is largely one of obstruction. Parliament under his leadership has served as a graveyard for reform. Key financial accountability measures have been buried. Presidential elections were stalled for years. Investigations into the Beirut port explosion and banking sector fraud were sabotaged with his quiet blessing.

Still, Berri remains indispensable to the system he helped engineer. Sectarian politics insulate him; international actors, fearing a vacuum, treat him as a necessary evil. But inside Lebanon, the patience is gone. Protesters chant his name with venom. His family’s wealth and visibility are symbols of elite impunity.

That a Berri in-law and his politically connected brother can walk into U.S. investment summits while ordinary Lebanese face blackouts, food insecurity, and blocked bank accounts, is not merely offensive—it is clarifying. Lebanon’s crisis is not accidental. It is the product of elite capture and international indulgence.

Lebanon is now a failed state in everything but name. Its currency has collapsed. Its institutions are hollow. Its elites are richer than ever. And its speaker of parliament—unchanged for 33 years—sits at the very heart of the wreckage. For all the talk of reform, Berri is a reminder that Lebanon’s problem is not just bad policies. It is a political class that has mastered survival while the country beneath them dies.

Nabih Berri will remain speaker not just of Lebanon’s parliament, but of its long, slow death. Until figures like Nabih Berri and the networks they anchor are confronted—rather than celebrated—there can be no real path forward for Lebanon.

John Smith is a law enforcement professional with decades of experience in risk, sanctions, and compliance.