For decades, the United States stood as the embodiment of capitalism’s promise—an open market economy where innovation, investment, and individual enterprise fueled not just prosperity, but unprecedented global power. Throughout the 20th century, the U.S. leveraged its financial systems, corporate reach, technological leadership, and cultural influence to build an international order shaped largely in its image.

China studied that success story—and decided to rewrite it.

Image by ChatGPT.

Chinese leadership watched how the U.S., through profit-driven capitalism, created a platform for global dominance. Not through conquest, but through a distributed web of economic control: the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency, Silicon Valley as the center of digital life, Wall Street as the epicenter of capital, and a military-industrial complex underwritten by unmatched economic scale.

But unlike the U.S., China did not leave its ascent to market forces alone.

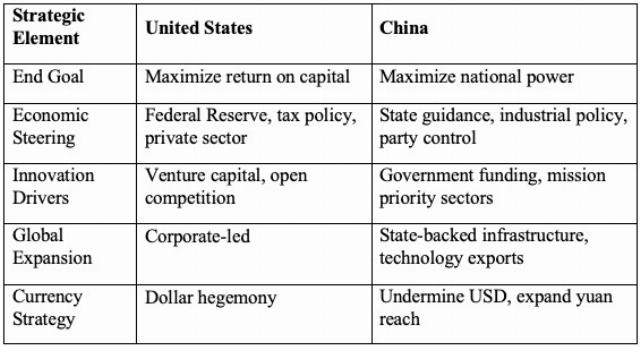

Instead, it began building what might be called power-directed capitalism: a hybrid model in which market mechanisms are permitted—encouraged, even—but only insofar as they serve the strategic goals of the state. The key difference is “purpose..”

Whereas the U.S. system directs economic policy toward capital gains, shareholder value, and private innovation, China channels its economy toward national power, strategic self-reliance, and global influence.

China’s model isn’t a rejection of capitalism—it’s a recalibration. Capital is still deployed for growth, competition still exists, and private enterprise plays a major role. But all of it occurs within strategic boundaries set by the Chinese Communist Party. Entire industries—AI, quantum computing, green energy, semiconductors—are not just markets; they’re battlegrounds for future supremacy.

Initiatives like Made in China 2025 and the Belt and Road Initiative aren’t just economic programs—they’re deliberate efforts to dominate supply chains, write global standards, and entrench Chinese influence in regions where Western liberal capitalism has retreated or stagnated.

Perhaps most importantly, China recognized that the U.S. didn’t set out to dominate the world through capitalism—it just did.

It allowed its markets to expand, its corporations to grow, and its innovation to flourish. In doing so, it inadvertently created a structure in which global systems—from payment platforms to mobile operating systems to trade rules—began to orbit around American institutions.

China has taken that lesson and asked, “What if we made that orbit intentional?”

The result is not a clash between capitalism and communism. It’s a competition between two models of capitalism:

Both models work—but they serve different masters—and aim for different futures.

The challenge now for the U.S. is not whether it can “beat” China at capitalism, but whether it can adapt its own model to compete strategically, not just economically.

Because in Beijing, they’re not playing for quarterly earnings…they’re playing for history.

Which System Will Prevail?

China’s system is smart, adaptive, and deeply strategic. But it also faces a structural limitation: no committee of experts—no matter how brilliant—can outthink the emergent complexity of millions of independent actors making self-interested decisions.

That was Adam Smith’s point when he described the “invisible hand”—not as ideology, but as a recognition of how decentralized market forces create order from seeming chaos. U.S.-style capitalism thrives on that chaos. Its openness to disruption, failure, and reinvention gives it a resilience that centralized systems often lack.

Beijing’s economists are brilliant, but brilliance alone cannot simulate organic innovation, cultural momentum, or the trial-and-error energy of free enterprise. China may dominate select sectors through directed investment, but at what cost? Over time, overcorrection, rigidity, or fear of failure can suffocate the very risk-taking that technological leadership requires.

China bets that power can guide the market. The U.S. bets that the market is the power.

The answer may not lie in which system is more efficient in the short term, but in which can best adapt to change in the long term. And so far, the unseen hand has proven surprisingly hard to outmaneuver.