The tale of two brands— Bud Light and Cracker Barrel—is nothing new, oft repeated, nonetheless instructive.

Bud Light, the erstwhile dominant beer brand, was napalmed by its own marketing brainiacs, driven by their destructive ideology as they tried to implement a bizarre customer replacement theory by changing their marketing, not their product.

Bud Light’s brewery formula and its taste remained unchanged. The shape of its bottles and cans, and the mechanism to open either were the same. And Bud Light didn’t change the shape, look, or feel of taverns, bars, or football tailgaters. Bud Light simply told its customers “bugger off,” “take a hike,” and “we want someone else to yank our tabs, and twist our caps.” It was a change of style over substance.

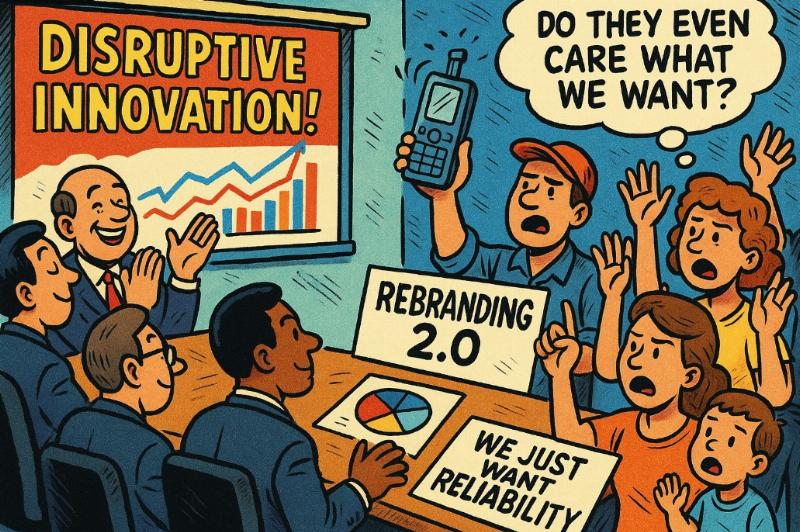

Image created using AI.

Cracker Barrel, in contrast, tried to pull a full tillage moldboard plow over and through its customer base by turning over everything about itself: reworking the type and quality of the food (which went from pedestrian to worse than combat MREs), bulldozing the physical décor and surroundings, and switching from fake country store to 1970s bus terminal lounge. It was a different type of change but, as with Bud Light, its sins were arrogance and stupidity.

Of course, CB’s college-educated, upper-class management loathed its customers—deemed lowbrow and unsophisticated. Yet those same forgettable loyalists repeatedly lined up in front of CB’s cash registers, while leaving generous tips. No longer.

Both Bud Light’s and Cracker Barrel’s upper-level management engaged in a sort of abstract self-deluded expressionism in which a shallow self-identity collided with the objective reality experienced by existing—and soon to be former—customers. Both failed amidst dazzling self-inflicted fireballs.

What they missed entirely is that your brand isn’t what you say it is. Your brand is what your customers or constituents (or ex-customers) say it is.

Organizations—institutions and companies-- “unexpectedly” arrive over Niagara Falls without a barrel when their self-labeling or aspirations don’t match what outsiders believe the product is (both as a product and as an image), and how outsiders respond to the company’s acknowledging that perception or rejecting it (in which case they decisively close up their wallets).

When self-identity diverges from external reality, marketing and communication strategy “experts” seek the convenient path in creating alignment. They try to control the dials for cosmetic messaging, completely ignoring the substance of what they are selling and delivering. Who needs customers anyhow?

What are you selling? Does that match what customers say they are buying or want to buy from you? Why would customers line up in front of your cash registers?

No one inside the notable brand failures has ever possessed the humility to ask such questions, much less pay attention to the answers.

Do you remember Michael Moore (yes, I know he’s an insufferable boob) challenging Ford CEO Alex Trotman to change the oil in a Ford Explorer? Well, Trotman did it, explaining the whats and whys of oil pan drain plugs, different oil grades, and filters, for which he received rave reviews from Ford owners and mechanics. “Quality is Job One” was Ford’s slogan, aligning the company’s brand with its customers. And so, the F-series Ford trucks have been the top-selling brand for 50 years.

Instead, brushing aside a similar invitation, IBM chief Louis Gerstner refused—or more likely didn’t know how—to format a floppy disk. Of course, Roger Smith, CEO of General Motors, couldn’t be bothered to even acknowledge Moore’s not-so-subtle assertion that most major brand titans give the proverbial middle finger to their customers.

Sometimes, brand failures are not deliberate re-makes, but victims of internal corruption, and willful isolation from customers, constituents, or faithful believers.

The most spectacular and tragic “brand” failure has been the Roman Catholic Church. In pre-Vatican II days, most notable for the 1570 Council of Trent Tridentine Latin Mass, the Church was the font of the magisterium, the mysteries of the Incarnation, Death, and Resurrection of Jesus Christ, the transubstantiation of the Eucharist. And of course, doctrinal rituals—fish on Fridays, abstinence, priesthood celibacy, and large families, plus intellectual rigor—all interwoven with authority and obedience.

But as widespread sexual abuse of minors by Roman Catholic priests was uncovered writ large in the 1990s, not only the priesthood, but more so, the basic tenets of the faith and doctrinal nihil obstat were deeply tarnished, immersed in skepticism, hypocrisy, cover-up, denial, and moral turpitude, inhibiting the glorious institution’s teaching of Grace and Truth.

Not to be overlooked, Disney’s profane missteps, or more accurately self-immolation, are best described by Breitbart’s entertainment media critic John Nolte:

Due to its dual obsession with sexual perversion and identity politics, Disney has not only destroyed its own brand but four of the greatest, most surefire, and beloved brands in movie history: Star Wars, Marvel, Indiana Jones, and Pixar.

Those golden geese are dead, bludgeoned by immature, sexually obsessed, hyper-partisan losers who no longer care about telling stories.

Revealed truth and beauty over 2000 years can be ambushed by only a few decades of arrogance and corruption, betraying a sacred institution.

The chronicles of secular iconic brands, whose market values can be quickly extinguished by their stewards repudiating their own customers, are well trodden, dog-eared, and bookmarked with hubris, toxic ideology, and stupidity.