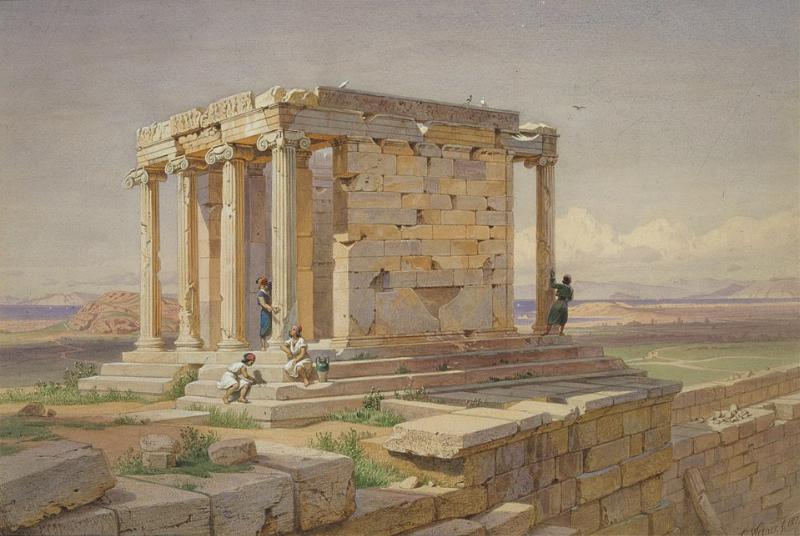

From Wikipedia Commons: The Temple of Athena Nike (Werner Carl-Friedrich, 1877)

The story goes that academics and other intellectuals suffered a deep crisis of identity and values in the wake of WWI. The horrors had exposed the destructive potential of industrialized modernity and shattered old certainties. This acknowledgement bred widespread self-contempt, prompting critical reassessment of Western civilization, especially its traditional aesthetics and cultural norms.

Supposedly, the collective trauma instilled a disillusionment with classical forms, ornamentation, and historicist architecture that symbolized the old order — seen as complicit in the social and political failures leading to war.

In the interwar period, a self-critical spirit fueled avant-garde architectural movements — side by side with revolutionary mass movements such as Communism and National Socialism — aimed at reshaping society and the individual. The idea was that new forms of architecture would create new ways of living, thinking, and interacting — essentially creating a utopian new world.

With their emphasis on functionality, simplicity, rationality, and universality, modernism and the International Style became emblematic of this revolution. Architecture refused to remain pure art or decoration — “beauty for its own sake”, as it were. Ideologically inflated, it had to serve a higher purpose to be worthy of existence; it was to make itself available as a tool for “social engineering” and “progress”. In this spirit, both Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) and Le Corbusier (1887–1965) sought to reshape man himself by providing living environments that would foster new social behaviors, healthier lifestyles, and a break from the ethical-aesthetic “chaos” of the past.

Throughout the history of Western architecture, classical forms have repeatedly emerged as an embodiment of humanity’s highest aspirations — order, beauty, and harmony. Rooted in the Renaissance exploration of Greco-Roman models, the classical tradition finds one of its most influential figures in Andrea Palladio (1508–1580), whose architectural principles set a standard for proportion, symmetry, and monumentality. The Palladian style became a cornerstone of Western architectural heritage, symbolizing civilization’s belief in reason and cultural continuity. Yet, the modern age, sacrificing eternity, has witnessed a radical rupture with these ideals.

The rise of modernism, with its revolutionary nihilism and contemptuous disregard for tradition, has led to widespread alienation and a crisis in architectural meaning. Around the world, the International Style has gained prominence — a “style” characterized by a lack of style and historical awareness, but with unimaginable cultural sacrifices on its conscience.

In this context, the revivalist work of architects such as Quinlan Terry (1937–), coupled with the philosophical advocacy of Roger Scruton (1944–2020), offers a potent response — celebrating harmony, beauty, and a calm belief in civilization and humanity through the time-proven language of classical architecture.

A student of Vitruvius (70–15), Palladio stands as a towering figure in architectural history. His treatise, “The Four Books of Architecture”, codified a set of design principles based on the harmonious proportions of the human body and classical antiquity. Villas and public buildings drawn by him combine monumental forms with organic motifs derived from nature, orchestrated into a balanced whole that communicates stability and beauty. The scope of this architecture goes far beyond the decorative. A declaration of aesthetic conviction, it is also deeply symbolic: it reflects a worldview where order and harmony mirror the cosmos and human reason.

The Palladian revival, whose derivative styles (e.g. Baroque, Beaux Arts) dictated public building design until WWI, embodies a yearning for this ideal order. Architects like Terry create buildings that resonate with the same proportional rigor and use of classical motifs. His work exemplifies the monumental scale and clarity of classical forms, integrating organic motifs such as acanthus leaves, columns, and pediments, which root the architecture in a natural yet refined language.

Terry’s work is a deliberate counterpoint to the dominant trends of 20th-century modernism. At a time when architects mostly followed the flow and abandoned historical reference in favor of abstraction, he himself stood out from the majority of his colleagues and reaffirmed the value of classical architecture as a living tradition. Whether private residences or public institutions by design (e.g. a cathedral or library), his buildings convey a calm dignity, reflecting an unshakeable belief in civilization’s capacity for continuity and beauty.

One notable example is Ferne Park, a country house in Wiltshire completed in 2001, where Terry applied Palladian symmetry, classical orders, and organic detailing to create a harmonious yet monumental residence. Another is the Paternoster Square redevelopment near St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, whose original plans Terry contributed to, blending classical urbanism with modern needs while respecting historical context.

Terry’s approach highlights the idea that architecture is so much more than a functional necessity or stylistic (geometric-artistic) experiment; it is a cultural expression of shared values. His meticulous attention to detail and use of classical orders create spaces that engage the human spirit, inviting occupants to participate in a timeless dialogue. In this way, Terry’s architecture becomes a celebration of beauty — not superficial ornamentation but a manifestation of deeper harmony and proportion.

The conservative philosopher Scruton was a thoughtful voice in the defense of traditional aesthetics and classical architecture. For him, architecture embodies the belief in civilization and humanity — it is a language through which societies express their identity, history, and values. He lamented the rise of modernism which he saw as fostering alienation by rejecting inherited forms and meanings.

Scruton held that beauty is a fundamental human need — not a luxury. He saw beauty, especially in architecture, as essential to civilizational continuity, cultural identity, and spiritual well-being. For him, classical architecture embodies this ideal: it is grounded in proportion, harmony, craftsmanship, and tradition. These qualities, he argued, express a respect for human scale, community, and the accumulated wisdom of the past.

Classical architecture, in Scruton’s view, was “civilizing”. It connected people to their heritage and environment, offering stability and meaning in public and private spaces. By contrast, he was deeply critical of modernist architecture. Perverted by abstract theory, utilitarianism, and ideological thinking (e.g. Le Corbusier’s “machines for living”), it left but ugly, monotonous, and oppressive environments behind. Like a mirror of totalitarianism.

Classical architecture’s use of organic motifs — stylized natural elements like vines, leaves, and flowers — imbues buildings with a sense of life and connection to the natural world, even as their monumental forms communicate order and permanence. This duality reflects a profound philosophy: civilization is not an artificial imposition but an extension of the natural order, mediated through reason and culture.

The monumental scale of classical buildings reinforces their symbolic role as civic landmarks and repositories of collective memory. They stand as enduring witnesses to humanity’s achievements, inspiring awe without overwhelming the human scale. In contrast, many modernist structures either disregard human scale or impose alien geometries, contributing to feelings of dislocation — and existential depression (melancholia).

The 20th century’s embrace of modernism was driven by a revolutionary zeal — to reinvent architecture in the face of industrialization, war, and social upheaval. This movement rejected classical orders and historical references in favor of abstraction, new materials, and functionalism. Much as modernism brought innovation, as if that were a value in itself, it introduced nihilism — a rejection of tradition without a clear alternative vision of meaning.

This nihilism has manifested itself in architectural environments that are generally found alienating: spaces that prioritize efficiency over comfort, minimalism over ornamentation, and novelty over continuity. Such environments feel utterly disconnected from local culture and human needs, leading to heartfelt criticism and a yearning for architecture that restores a sense of belonging and beauty.

The revival of Palladian and classical architecture by figures such as Terry, coupled with Scruton’s philosophical defense, represents a vital reclamation of architecture’s purpose as a mirror of beauty, harmony, and belief in civilization and humanity. Classical architecture, characterized by monumentalism, organic motifs, and proportioned harmony, affirms values that transcend time: order, dignity, and a divine connection between the natural and cultural world.

In an era marked by the alienation caused by modernist revolutionary nihilism, this return to tradition is anything but nostalgia; rather, it is a profound statement about the human spirit’s enduring need for meaning and beauty. Architecture, when it embraces its classical heritage, becomes a vehicle for social cohesion, cultural continuity, and the celebration of what it means to be human.