On August 19, 2025, the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform escalated its scrutiny of Gavin Newsom’s vanity project: a high-speed railway that was originally supposed to connect California’s major cities by 2020. Congressional Oversight may mark the final phase in the latest review process that began in October 2024. This is not the first time the project came under federal fire — an earlier FRA review in 2019 led to the termination of a key grant, which was later reinstated on a smaller scale in 2021 and tied to the Central Valley segment.

Specifically, the other important FRA review in 2019 occurred under the Trump administration. It led to the termination of an FY10 agreement to connect San Francisco and Los Angeles. However, the project was reinstated in June 2021 under a settlement between the Biden administration and California. The settlement restored nearly $1 billion in federal grant funding, tying it back to the Central Valley segment, known as the Merced-Bakersfield (M-B) Early Operating Segment (EOS).

The Oversight Committee wants to know whether the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) knowingly misled federal officials to obtain taxpayer funding. Chairman James Comer (R-Ky.) demanded internal documents, communications, and staff-level briefings on whether the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) misled federal officials about ridership, costs, and timelines to secure billions in funding for the project. The committee set a deadline of September 2, 2025 for the Department of Transportation (DOT) to respond.

History of a Train to Nowhere

In 2008, California voters approved the construction of an 800-mile statewide high-speed railway with “$9.95 billion dollars of state bond funding,” according to a letter sent by Comer to Transportation secretary Sean P. Duffy. The boondoggle has been characterized as “perhaps the greatest infrastructure failure in the history of the country,” according to the Hoover Institution.

The rail project was initially projected to be completed in 2020, with a projected cost of $33 billion. However, updated cost estimates, according to the August 19 letter, now “range from $89 billion to $128 billion,” with a projected completion date sometime around 2032.

The Oversight letter states that the “Biden administration committed roughly $4 billion in federal taxpayer dollars to the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) project, including almost $89.65 million dollars in the closing days of the administration.”

Delays, cost overruns, and political fights forced CHSRA to narrow its focus to the Early Operating Segment (EOS) — the 171-mile corridor between Merced and Bakersfield — which cooperative agreements require to be in high-speed operation by December 31, 2033.

According to the June 4 report, the rail project has already received “approximately $6.9 billion in federal dollars” over a 15-year period, yet not a single mile of high-speed track has been laid. Instead, much of the federal funding has gone into construction packages for bridges, viaducts, and earthworks. Other funds have been spent on land acquisition; relocation of utilities; planning and environmental reviews; and lawsuits, settlements, and bureaucratic overhead.

Phase 1 (about 520 miles) of the project was designed to connect Northern and Southern California in under three hours. Phase 2 (about 280 miles) was designed to extend north to Sacramento and south to San Diego, but it is contingent on the completion of Phase 1. The Merced–Bakersfield corridor is a subset of the larger Phase 1 alignment.

Duffy Initiates Review of CHSRA Rail Project

Duffy announced his intention to review the project on February 20. The probe targeted two significant grants — the 2010 $929-million cooperative agreement and the newer $3.07-billion agreement. The investigation aimed to determine whether CHSRA adhered to grant terms, including oversight of performance, risk, and financial accountability for roughly $4 billion in federal funding. As part of the review, the FRA conducted site visits, risk assessments, document reviews, and meetings with state oversight entities and CHSRA staff.

Duffy’s February 20 letter to Ian Choudri, CEO of the CHSRA, mentions an annual monitoring review conducted by the FRA on October 23, 2024. That review identified six key areas of interest, though specifics were not fully disclosed, raised concerns about CHSRA’s ongoing performance and adherence to grant conditions.

The letter also references a February 3, 2025 report from the CHSRA’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG‑HSR) evaluating the schedule for the EOS M-B segment. Briefly, the report stated that the M-B segment completion would be significantly delayed because of scheduling changes due to deviations from “procurement and funding strategies.”

On June 4, the FRA published a 310-page compliance review, accompanied by a formal letter to CHSRA, finding no viable path for project completion. The report cited numerous delays, cost overruns, failure to procure rolling stock, and a $7-billion funding gap — despite CHSRA having already received nearly $6.9 billion in federal grants, with no miles of high-speed track laid under those grants.

Reportedly, $3.5 billion of the $6.9 billion came from the Obama-era American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Nine hundred twenty-nine million was awarded in FY2010. Approximately $2.5 billion came from later federal-state partnership (FSP) agreements. The EOS M-B segment was projected to cost around $30 billion, yet California has identified only $21–23 billion in funding, leaving an unfunded gap of $7 billion.

Duffy gave the CHSRA 37 days to respond or risk losing the two federal grants. However, the CHSRA’s responses failed to satisfy Duffy’s concerns. On July 16, 2025, acting FRA administrator Drew Feeley finalized the decision to terminate the two federal grant agreements, effectively pulling back the remaining $4 billion in federal funding. Feeley stated in no uncertain terms the findings that led him to the “unavoidable conclusion that CHSRA would not be able to deliver the operation of a Merced-to-Bakersfield corridor by the end of 2033.”

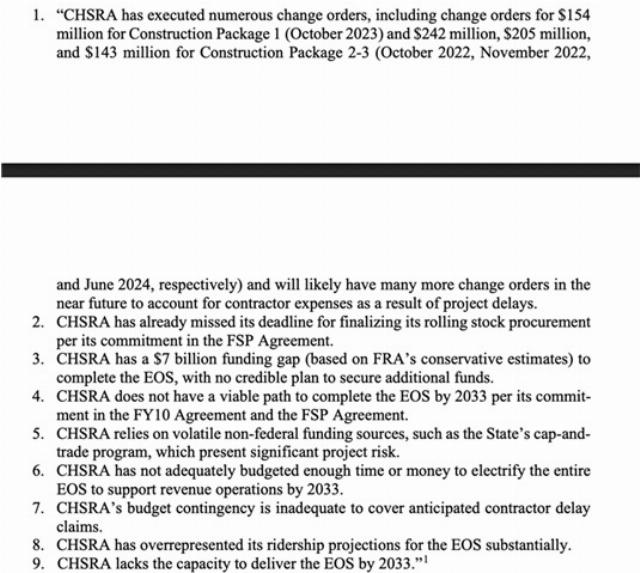

Feeley asserted that the CHSRA had failed to comply with the “cooperative agreements,” making termination inevitable. The CHSRA responded immediately with a legal challenge, alleging that Feeley’s take was politically motivated. However, the findings listed in the letter would suggest otherwise. Feeley contends that there is no viable path to completion with a $7-billion funding gap with no credible plan to fill the gap, among the other reasons listed below.

Importantly, an agreement between the CHSRA and the FRA places the $4 billion in federal funding into a trust account to “keep the grants intact,” pending resolution of the complaint. Choudri blasted the June 4 compliance review as “based on an inaccurate, often outright misleading, presentation of the evidence.”

Secretary Duffy wants to de-obligate the unallocated $4 billion in taxpayer dollars and reallocate them to more viable passenger rail and infrastructure projects elsewhere in the U.S.

Lee Ohanian, writing for the Hoover Institution, explains the rationale for the reallocation of federal funding,

Even a favorable reading of CHSRA’s defense fails to concretely explain how the Authority will complete the scaled-down project, let alone revive the original vision that was promised to voters. The problems at hand with high-speed rail are not political — they are structural and have been part and parcel of the project since 2008. The FRA’s decision to defund is founded on a chronic pattern of overpromising and underdelivering that has eroded credibility to the point where there is none left. Federal infrastructure funds are scarce, and federal oversight must ensure that they are being invested in realistic, high-return projects.