Three days ago, the Supreme Court granted a stay of a court order blocking Donald Trump’s ability to deport illegal aliens to countries other than their legal residences. The Trump administration was contesting an order from Boston-based U.S. District Court Judge Brian Murphy, who had held that the deportees had a right to contend they’d be unsafe in their proposed new destinations. In her dissent to the Supreme Court ruling, Sotomayor cited the UN Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, but, as is so often the case, I think she’s gotten it wrong—at least, as to many of the deportees.

For some months, Judge Murphy has been desperate to keep illegal alien gang members in America. In April, he blocked the administration from deporting violent criminal illegal aliens to countries other than those in which they were citizens, even after they’d exhausted all legal appeals to remain in America.

The problem, according to Murphy, was that they might be unsafe in the destination country and, therefore, were entitled to “a meaningful opportunity” to contest their destination. For example, a Guatemalan gay man with a criminal record, claimed that he’d been gang raped in Mexico by homophobes. Others were worried about rival gangs or just the general criminality in the destination country.

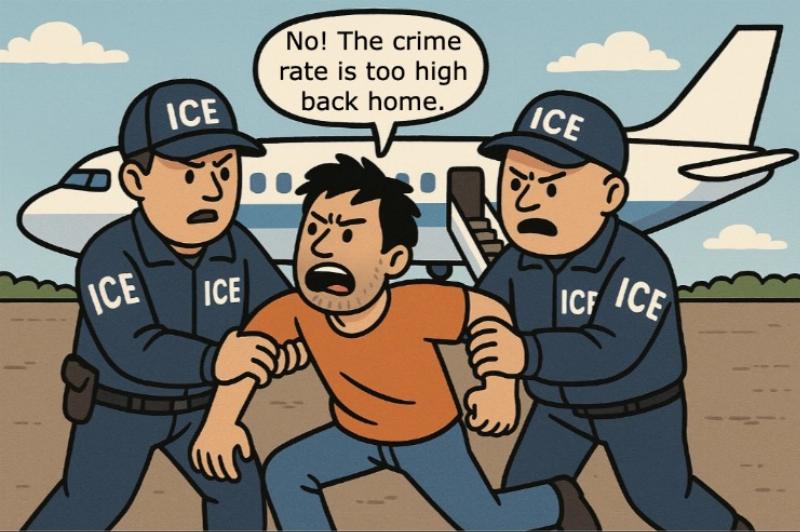

Image created using ChatGPT.

Eventually, thanks to Murphy’s efforts, eight men—all of whom were convicted of serious crimes, such as murder—ended up detained at a military base in Djibouti. It was this status quo that the Supreme Court said could change, with the Trump administration enabled to remove the men to their final destination.

Despite the Supreme Court’s order, Murphy promptly announced that it didn’t really apply to him, and that he still has full authority to rule on cases involving illegal aliens being deported to countries other than the lands of their legal citizenship.

To support his position, Murphy ignored the actual stay order and, instead, found succor in Sotomayor’s dissent:

“[T]he District Court's remedial orders [were] not properly before [the Supreme] Court because the Government has not appealed them, nor sought a stay pending a forthcoming appeal,” he quoted from her writing, joined by the court's two other liberal justices, Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson.

The Trump administration promptly went back to the Supreme Court for clarification. So, that’s the procedural background.

What’s more interesting (and I honestly never thought I’d say this) is Sotomayor’s dissent in Department of Homeland Security v. D.V.D. That’s because she justifies her position, not primarily on American law, but by looking to the 1984 UN Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, to which the U.S. is a signatory:

Noncitizens facing removal of any sort are entitled under international and domestic law to raise a claim under the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Dec. 10, 1984, S. Treaty Doc. No. 100-20, 1465 U. N. T. S. 113. Article 3 of the Convention prohibits returning any person “to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.” The United States is a party to the Convention, and in 1998 Congress passed the Foreign Affairs Reform and Restructuring Act to implement its commands. The Act provides that “[i]t shall be the policy of the United States not to expel, extradite, or otherwise effect the involuntary return of any person to a country in which there are substantial grounds for believing the person would be in danger of being subjected to torture, regardless of whether the person is physically present in the United States.” §2242(a), 112 Stat. 2681-822, codified as note to 8 U. S. C. §1231. It also directs the Executive to “prescribe regulations to implement” the Convention. §2242(b), 112 Stat. 2681-822. Those regulations provide, among other things, that “[a] removal order . . . shall not be executed in circumstances that would violate Article 3.” 28 CFR §200.1 (2024).

This isn’t the first time the anti-torture Convention has popped up. Just today, in Riley v. Bondi, the Supreme Court issued a very procedurally dense decision about whether a Board of Immigration Appeals denying deferral in a “withholding only” proceeding is a final order. (It isn’t.)

What interested me more was something the case didn’t really discuss. That’s the fact that the illegal alien claimed that, under the UN’s anti-torture Convention, he had to remain in America because, if returned to his native Jamaica, he risked being killed by a “drug kingpin.”

As you recall, Kilmar Abrego Garcia managed to wangle what seemed like a permanent stay in America because he said he was at risk of death, not from his government, but from a rival gang member. I bet that other illegal aliens are making the same claims. I’m also sure that Sotomayor, if asked, would say that the UN anti-torture convention covers all these claims.

But does it really? Is the U.S. barred from sending illegal alien criminals in America back to their home countries because they’re afraid of rival gang members? Or, if these same criminal illegal aliens refuse to go back home, can they be protected from going to third-party countries that are simply lawless places where they might get hurt? Probably not.

You see, if you read the convention, the core issue—torture—applies only to government actions within the country at issue:

For the purposes of this Convention, the term "torture" means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions. (Emphasis mine.)

Our refugee and sanctuary laws were intended to protect people facing government-sanctioned annihilation, and that is consistent with the UN anti-torture convention. Our laws do not exist to protect illegal aliens whose criminal pasts mean they made bad enemies in their home countries or who prefer the safety America offers to living in a country that is one giant bad neighborhood.