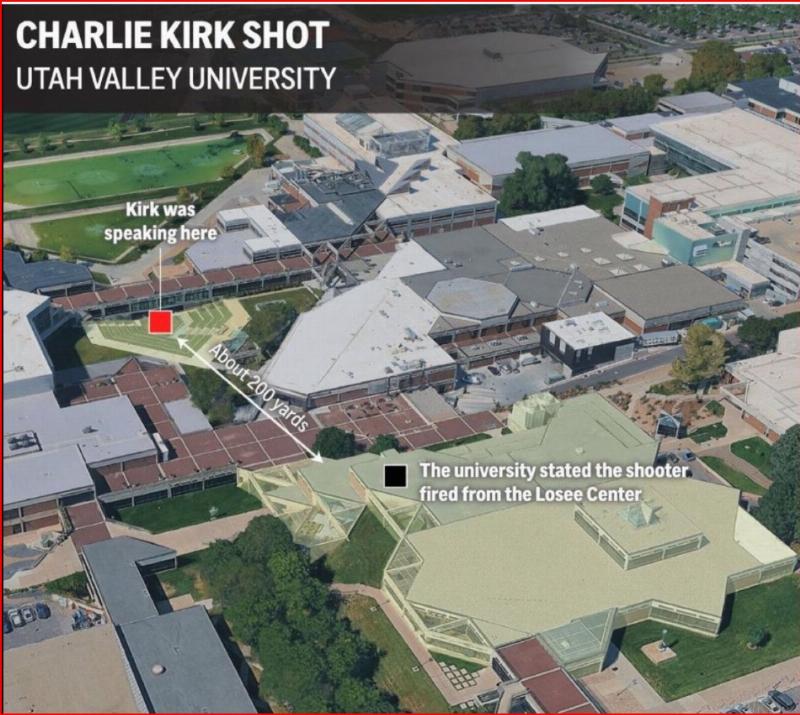

Since I first heard of Charlie Kirk’s assassination, I’ve been pondering whether a lifelong shooter’s perspective on the murderous sniper who took Charlie Kirk’s life would be welcome, as well as speculating how he did it.

After I saw Fox News cover that aspect of the assassination around 6:00 a.m. Eastern this morning, I decided this perspective might prove helpful to non-shooters who are wondering: “How did that monster shoot Charlie Kirk’s small-target carotid artery with such precision from 200 yards away?”

Soldiers are carefully trained to aim at what’s called “center mass.” This is a point where the ribcage meets the diaphragm – the largest vulnerable target in the human body. Combat snipers are taught to aim for a “kill shot” that either shreds the human heart or pierces the skull, destroying the brain within. Either of those targets lead to almost instant destruction of one of the two most vulnerable organs in the body. A shot to either one is followed by an almost instantaneous death. They are not trained to hit the carotid. Nobody trains for such a shot, not the best snipers. It’s just too chancy.

There are other reasons for all but the most seasoned professional snipers or master target shooters to aim for anything but “center mass.”

While shots to the neck can deliver one-shot, one-kill performance, they are fraught with risk. Keep in mind that hearts and heads are remarkably small targets, even when seen through a sniper scope. Factors that can cause shooters to miss include the weight of the bullet, ambient wind speed, especially cross-winds – which pushes a bullet off course – and gravity. That latter factor is especially important when the shooter is lying on a building’s flat roof, targeting someone who is well below the shooter’s platform. Unless you’ve really practiced in the skills for downward shooting, you really can’t imagine how much gravity affects the barrel-to-target shot.

While I’m not a trained sniper, I am a military-trained target shooter. In college, I shot on the University of Georgia rifle team. Our “coach” was a career senior sergeant assigned to our ROTC unit. He took his duty seriously, knowing that, given this was during Vietnam, some of us might soon wind up in combat.

Even for someone who’d been target shooting since he was 12, qualifying for the team wasn’t an easy task.

In addition, I won a Presidential Sports Award for my shooting skills.

Still, the top contenders on our team were amazingly precise shooters, well beyond my skill level. To compete and win, they did everything possible to overcome the factors that went into competitive shooting.

Applying those lessons, and using specially manufactured one-shot, incredibly precise Anschutz target rifles, shooting precisely-crafted ammunition at an indoor range with no air movement and no added gravity drop, we wore carefully-designed metal-reinforced leather vests that limited movement and all but eliminated any internal quivering or twitching.

Still, only a few of the best on our team could consistently shoot bullseye targets with a precision that scored above 290 out of 300, even without the near-combat stress any assassin might feel.

Since my college days, I’ve always had rifles and always shot targets. I’ve got nothing against hunting or hunters, but that’s not my game. At my best aiming in long-distance shooting, I could hit a metal target from 440 yards. That’s roughly a quarter mile, about twice the distance of the assassin. For this kind of shooting, I shot a surplus Mosin-Nagant – the basis of the Soviets’ incredibly-effective sniper corps used in World War II.

However, mine did not have a sniper scope – I used the “iron sights” that came with the rifle. I shot heavy full-metal jacket rifle rounds, the best readily available ammunition for target shooting the Mosin-Nagant. It resisted the impact of breezes, as well as the force of gravity, better than most. The man-sized metal targets provided an audio signal, telling me that the target had been struck, letting me know what I could do.

Based on a lifetime of target shooting with long-arms, here is what I believe the assassin did:

Media reports said he shot a high-power rifle. Given his relative accuracy, he’d have been shooting heavy, streamlined ammunition. Not specialized hunting ammunition, but ammo designed for long-range target shooting. This isn’t the most deadly ammunition available, but if it hits center mass, it’s deadly at 200 yards.

Because the assassin was far above his target, he was likely aiming, not for center mass, but – anticipating the gravity drop – above the center mass, perhaps targeting the head. To avoid the gravity issue, he overcompensated, shooting too high to hit center mass. The victim’s carotid wasn’t his target – it’s too small. Aiming high, either because he wasn’t as good as he thought, or because he overcompensated for the gravity-drop, meant he hit the carotid.

Since his target was sitting on a stage at the bottom of an outdoor amphitheater, essentially unmoving, the bullet had a lot of gravity to contend with. It struck an area between the head and center mass. One of those was almost certainly his target. Striking carotid was pure bad luck for his target.

Few others – besides trained military or SWAT snipers – would even consider aiming at that small target from 200 yards. Since a miss would give his target a fair chance to get out of the line of fire before the next shot, only a deluded sniper would bet his skills on such a shot.

That’s my opinion.

If you hear from a SEAL Team Six or FBI hostage-rescue sniper, considering how really accurate his custom-built sniper rifle is, if he says he could make the shot, believe him. Then ask yourself, “what are the odds that this sniper would have the equipment, training and skill needed to make such a shot?”

Essentially no one but a military or FBI-trained sniper could make that shot, even with everything in his favor.

If you appreciate the quality of American Thinker’s content – content the late Rush Limbaugh called his “go-to show-prep source” – I hope you’ll join me by subscribing to American Thinker. Also, please consider making a one-time or periodic contribution to American Thinker. Charlie Kirk’s tragic death encouraged me to donate – I’m already a subscriber. So join me, please. Thanks.

Ned Barnett is a prolific writer and a regular content contributor to American Thinker. A long-time political activist – he worked with the late, great Lee Atwater in President Ford’s reelection campaign, along with many candidates for the US Senate, the House of Representatives and state Governors. Earlier this year, Ned ghost-wrote a campaign bio for a candidate running for Governor in the Midwest.

When he’s not being “political,” Ned ghostwrites books – 19 published so far. Ned also writes and publishes his own books as well – 41 and counting. He helps writers as a co-writer or writing coach. He helps authors “self-publish” their book, as well as promoting their books, which he’s done since 1982. For more information, contact Ned at 702-561-1167 or nedbarnett51@gmail.com.

Image: X screen shot