Tomorrow, Secretary of War Pete Hegseth brings hundreds of U.S. generals and admirals to Quantico for what amounts to a mass leadership formation.

The agenda is opaque, the logistics unusual, and the stakes high.

With President Trump now planning to attend, the gathering risks becoming as much a signal about civil-military relations as it is about readiness.

What should Americans take from it — and what should our flag officers hear?

First, let’s dispense with the novelty. Large, in-person convocations of nearly the entire general/flag officer corps are rare. Reporting indicates Hegseth intends to hammer “warrior ethos,” grooming and standards — an unmistakable course-correction message to a force that has struggled with recruitment, retention and public confidence. Whether or not every rumor about mass firings is overblown, the form and timing are extraordinary.

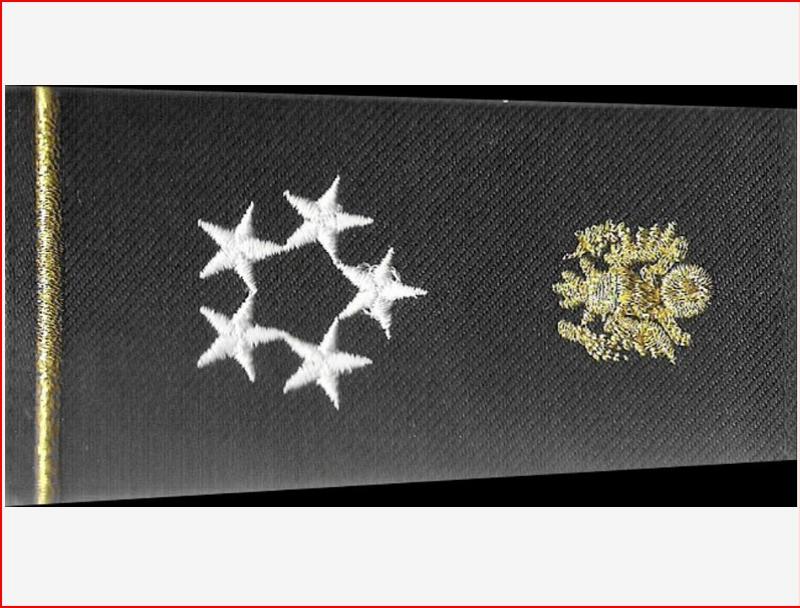

Second, size and scale matter. By Pentagon counts this summer, there are roughly 838 active-duty generals and admirals. Independent analysis notes that asking “about 800” to show up would approach the total population — hence the shock across commands. Even if the real attendance is lower due to staff exemptions, it’s still unprecedented.

Third, context matters. President Trump’s decision to appear adds a political charge no speech can avoid. Some will see a morale boost, others, politicization. In a constitutional republic, civilian control of the military is not theater — it’s principle. When hundreds of flag officers assemble under cameras and floodlights, allies and adversaries alike read the optics. That’s why clarity of purpose and restraint of tone matter as much as content.

Fourth, history matters — especially the comparison so many are already making.

At the end of World War II, about 12.2 million Americans were on active duty (roughly 16 million served at some point in the war), and there were a little over 2,000 general and flag officers — a ratio around 1:6,000. Today we have roughly 1.3 million active-duty personnel and about 800–840 flag officers — a ratio closer to 1:1,500. Reasonable people can debate the right number, but the trend line is undeniable: the GO/FO corps has grown as a share of the total force.

So, what should this meeting accomplish?

- Put “warrior ethos” back where it belongs: In readiness, not rhetoric. Fitness standards, small-unit proficiency, and combat-credible training are not partisan issues. They’re the bedrock of deterrence. If Hegseth focuses his charge on measurable outputs — deployable readiness, training reps that mimic the fight we face, and clear, published standards enforced without fear or favor — he’ll have broad support in the ranks and among taxpayers. Announcing a short list of concrete readiness metrics the services will publicly report would be a solid start.

2) De-politicize the flag ranks — by example as much as exhortation. The surest way to keep the military out of politics is for political leaders to keep politics out of the military. That cuts both ways. The Secretary can demand commanders enforce standards and shut down ideological litmus tests — from any direction. He can also reaffirm that promotions, billets, and reliefs will be based on performance and warfighting requirements, not Twitter storms or cable-news narratives. The presence of the Commander-in-Chief raises the temperature; the remarks should lower it.

3) Right-size and de-layer the headquarters without hollowing the force. If reductions to general/flag billets are coming, they should be targeted at overhead and staff inflation, not the command chains we’ll need on Day One of a crisis. The Department has lived through pendulum swings before. A principled framework — tie billets to mission, eliminate duplicative structures, shift resources to operational units — beats a blunt “slash the stars” headline. CRS has documented how the GO/FO share has crept up over decades even as end strength fell; use this moment to reverse bloat where it doesn’t touch combat power.

- Speak to the strategic environment plainly. While Washington fixates on the spectacle, Beijing, Moscow, and Tehran are counting cards. A mass stateside recall can be misread abroad. The message to the generals should be unambiguous: U.S. joint forces will maintain global command presence, allied obligations, and crisis response timelines uninterrupted. Any reorganization must enhance, not slow, the ability to surge combat power to the Western Pacific, Europe, or CENTCOM on short notice.

5) Restore trust with the country. The American people expect two things from their military: win wars and stay out of politics. The way to do both is to align words, standards, and structure with the mission. Invite public accountability — publish the metrics that matter, acknowledge where we’re short, and show the plan to fix it. That transparency will calm speculation and strengthen civilian confidence.

Critics will ask why convene everyone in person when secure video exists. It’s a fair question. But if Hegseth uses the moment to set unifying, apolitical expectations; to define readiness in terms that matter to warfighters; and to start carefully trimming bureaucracy so resources flow to the edge, the meeting will be worth the disruption. If it becomes a pep rally or a purge rumor mill, it will do more harm than good.

America has always course-corrected its armed forces in eras of danger. What we cannot do is confuse showmanship for strategy. The right charge to the flag ranks is broad brush on purpose — because the mission is. Demand a tougher force, a cleaner chain of command, a leaner headquarters, and a military that remembers who it serves and what it’s for. That’s a message worthy of bringing the generals home to hear.

Robert Maginnis is a retired U.S. Army infantry officer, a former Pentagon insider for decades and the author of Preparing for World War III.

Image: Wikimedia Commons, via Picryl // public domain