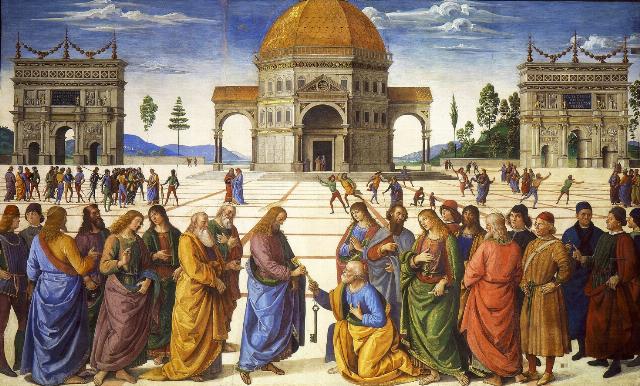

From Wikimedia Commons: Fresco in the Sistine Chapel, Rome: Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter (Pietro Perugino, 1481–82)

Architecture matters. Far beyond the requirements of shelter and utility, it conveys the essence of (a) being human, (b) civilization, and (c) institutional endurance. From the graceful villas of Andrea Palladio in Renaissance Italy to the monumental civic buildings of Washington, D.C., architecture reflects the values, aspirations, and identity of a people. Yet, the course of architectural history also reveals ruptures — moments when the connection between the built environment and the human condition frays, as seen in the stark Brutalism of the 20th century. Revisiting the lineage of Palladian architecture and its American heirs reminds us that buildings, apart from stone and mortar, are vessels of meaning that can elevate or degrade the public spirit.

In the quiet city of Vicenza, Italy, during the 16th century, a young stonecutter named Andrea Palladio was transformed into one of history’s most influential architects through the mentorship of Gian Giorgio Trissino. A nobleman and a Renaissance humanist, the latter was an individual steeped in classical learning, poetry, and philosophy. He recognized Palladio’s raw talent and introduced him to the ancient architectural treatises of Vitruvius and the ruins of Rome, unlocking a vision that would marry practical craft with the ideals of classical beauty.

Palladio’s architecture is distinguished by an extraordinary harmony of proportion, balance, and symmetry. His buildings — whether the serene Villa Rotonda or the civic Basilica Palladiana — embody a synthesis of ancient Roman principles with Renaissance humanism’s emphasis on order and rationality. However, beyond technical mastery, Palladio’s work reflects a deeper commitment: to dignify human life and create spaces where public and private realms may both flourish with nobility and grace.

Vicenza itself became a canvas for Palladio’s genius and ideals. The city’s transformation into a gallery of classical harmony was far from accidental but emblematic of the Renaissance’s spirit — an awakening to the capacities of human reason, the beauty of nature, and the power of tradition. Palladio’s architecture was a clarion call to civilization: that human-made environments should inspire virtue, stability, and civic pride.

Nothing like decorative excess, this architecture represented a language, a form of communication through columns, pediments, and proportional geometry. It spoke of enduring values, of a republic built on reason and law, where the individual and community were balanced in mutual respect.

Centuries later, across the Atlantic, the young United States looked back to these Renaissance ideals to shape its identity. Thomas Jefferson, an ardent student of classical architecture and Palladio in particular, envisioned a new nation whose buildings would reflect the dignity and permanence of its democratic ideals.

Washington, D.C., was conceived as a “New Rome”, a city where monumental architecture would not only house government functions but also proclaim the virtues of liberty, order, and public service. The Capitol, with its soaring dome echoing the Pantheon, and the White House, with its classical porticoes, stand as testaments to a deliberate cultural continuity. Here, Palladian principles of symmetry, proportion, and clarity become the language of statecraft.

This architecture is not cold or distant; rather, it is majestic and inspiring. It calls citizens to participation, to trust in the institutions, and to a shared destiny. The monumental scale and formal beauty communicate that these institutions are meant to last, to serve the public good, and to reflect the highest aspirations of civilization.

To understand why architecture holds such power over civilization and the soul, one must consider its philosophical foundations. Architecture, in its highest form, setting off from physical structures, is about shaping human experience and expressing metaphysical truths.

The Renaissance, inspired by the rediscovery of classical antiquity, revived the idea that the cosmos itself was ordered by harmony and proportion. Human beings, created in the image of a rational universe, could reflect this cosmic order through art and architecture. Palladio’s work embodies this conviction: buildings are microcosms of the universe, carefully composed to mirror natural laws and human reason.

Both Plato and Vitruvius viewed architecture as a moral discipline. The latter famously argued that good architecture requires “firmitas” (durability), “utilitas” (utility), and “venustas” (beauty). These principles reflect a balance between practical necessity and higher ideals. Distinct from decoration, beauty inspires reflection on the transcendental; it is the visible expression of truth and goodness. When a building is beautiful in this classical sense, it elevates the soul, instilling a sense of order and peace.

Moreover, architecture serves as a social text, communicating the values of a community. The grand columns and domes of the Renaissance palazzi or the Capitol building are not only structural features but also symbols of justice, stability, and collective identity. Architecture thus becomes a form of “civic pedagogy” — teaching citizens about their shared heritage and responsibilities.

The 20th century brought a rupture in this architectural lineage. Following the trauma of two world wars and rapid social transformation, architecture embraced new forms, engaging in social engineering. Brutalism emerged, characterized by raw concrete, stark geometric forms, and a focus on function over ornament. An ideological misfit, it was originally supposed to be honest, democratic, and reflective of a modern industrial society.

Ultimately, Brutalism conveyed the opposite of Palladian ideals. Its massive, fortress-like structures felt ominous and lifeless, alienating citizens from the very institutions that they housed. Instead of inspiring trust and civic pride, Brutalism symbolized institutional bureaucracy, social fragmentation, and cultural pessimism.

This rupture is more than stylistic. It mirrored a wider civilizational crisis — a questioning of long-standing values, an anxious modernity uncertain about its place in history. The break from classical beauty to functional rawness represented a deeper separation between society and its ideals, a loss of the architectural poetry that nourishes the soul.

Philosophically, Brutalism’s emphasis on raw materiality and unadorned function challenges the Platonic ideal that beauty is a reflection of an eternal order. In this view, architecture becomes primarily a “tool of utility”, losing its capacity to inspire awe and elevate the spirit. The result is a built environment that feels oppressive or indifferent to human dignity.

Architecture is a mirror, reflecting who we are and who we aspire to be as a people. The classical ideals embraced by Palladio and the founders of the United States show us that buildings can embody virtue, stability, and grace. They can create places where individuals feel part of something larger — of history, community, and purpose.

When architecture honors these ideals, it serves the lasting institutions of civilization: justice, governance, education, and culture. It nurtures the public spirit and strengthens the social contract.

Conversely, when architecture becomes alienating or merely functional, it risks reflecting a society fragmented, mistrustful, and disconnected from its heritage. The public realm suffers, and with it, the soul of civilization.

To build for the future is to build with reverence for the past and with hope for the public good. We do not seek a return to past forms as unreflected imitation, but a revival of the principles that made those forms powerful: harmony, proportion, human scale, and civic dignity.

The example of Palladio, shaped by Trissino’s mentorship and Renaissance humanism, reminds us that architecture can be a language of the soul — a discipline that expresses our collective dedication to civilization as human beings. Washington, D.C., with its neoclassical grandeur, stands as a monumental expression of this ongoing commitment.

In an age that risks forgetting these lessons, it is vital to remember: architecture matters. It shapes our experience, influences our spirits, and holds the potential to inspire generations to come.

Architecture is far more than a backdrop to history; it is a living testament to our values and aspirations. The lineage from Palladio’s Vicenza to the monumental capital of the United States shows how the built environment can dignify human life and sustain the institutions that serve the public.

When architecture is conceived with care for proportion, beauty, and public purpose, it nurtures the soul of civilization. When it is reduced to mechanistic functionality, it reflects and reinforces societal fractures.

As we confront new challenges in the 21st century, returning to these lessons is crucial. So, reach beyond utility and expediency, build for the soul of civilization, and create something that serves the public and inspires the human spirit, carrying forward the ideals of harmony, dignity, and institutional endurance.