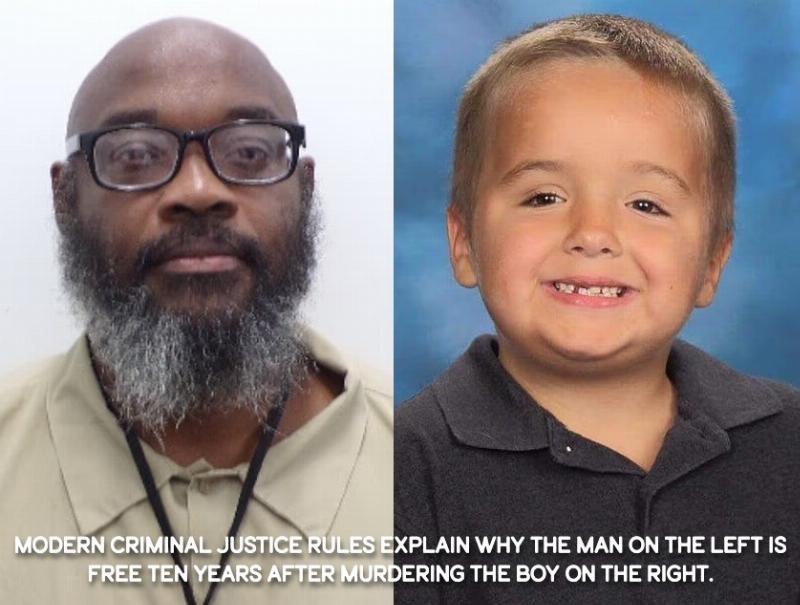

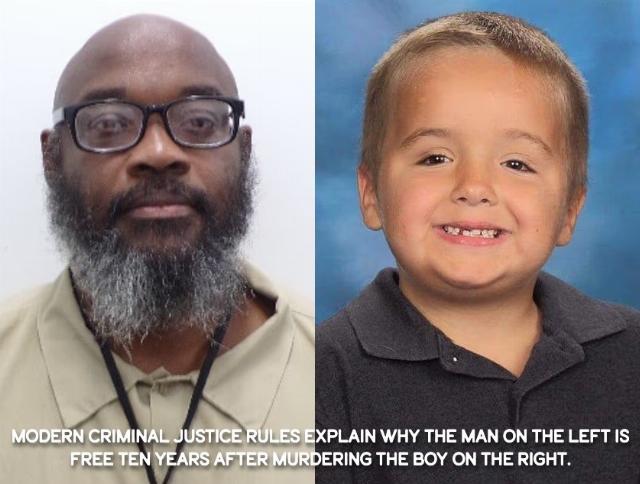

In 2015, Ronald Exantus broke into the Tipton home in Versailles, Kentucky, and violently attacked the family with a knife. The focus of his fury was six-year-old Logan, whom he stabbed so brutally that he bent his knife on the child’s skull.

Rather than being sentenced to death (or, at a minimum, life imprisonment) for murder, Exantus was charged only for assault, a limitation imposed “by reason of insanity.” On October 1, after serving only eight years (including time served before the trial), Exantus became a free man. How did this happen?

It all started in 1843, when the House of Lords formulated the M’Naghten rule:

...that every man is to be presumed to be sane, and ... that to establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.

Put another way, to raise the classic insanity defense, you must be so completely delusional that you don’t realize that you’re killing someone (for example, you think that you’re beheading a giant rattlesnake, not a person). Alternatively, you must be so completely insane that you don’t recognize that you’re not supposed to murder people.

Public domain images.

That last concept presumed a society in which everyone accepted both the Biblical commandment that “Thou shalt not kill” (actually, the Hebrew word is “murder”) and the state’s laws against murder. One of the things we’re witnessing in multicultural, morally relativistic Europe is the struggle to deal with an influx of people whose religious doctrines demand that they murder those who offend them in any way. But that’s another story...

In the old days, proving insanity was hard. You really needed to be a gibbering lunatic to win on the defense. Moreover, if you had reached a state of lunacy through deliberately ingesting intoxicating substances, that would not trigger the insanity defense. Back in the day, if you intentionally committed acts that destroyed your reason, that was on you. Or as Blackstone’s Commentaries said,

The law will not suffer any man to privilege one crime by another: a drunkard shall be punished for whatever ill he does in his drunkenness, as much as if he were sober.

This is a good rule. Unless you’re Cary Grant in North by Northwest, having bad guys pour alcohol down you’re gullet, if you choose to mess with your mind, you’re responsible for the consequences.

American courts used to apply the same rule, but many don’t anymore. For example, in Kentucky, if you voluntarily ingest drugs that reduce you to a condition that “Negatives the existence of an element of the offense,” then your intoxication itself becomes a defense against the crime...including murder.

The defense in Exantus’s case introduced evidence claiming that, before the murder, he wasn’t sleeping or eating, and that he heard voices speaking in Creole (although they were not telling him to kill). That would not have sufficed under the M’Naghton rule.

Meanwhile, the prosecution argued that Exantus wasn’t crazy; he was just acting out the effects of illegal drugs. On the minimal evidence available, this was a strange prosecutorial tactic because it triggered the Kentucky law about drugs, negating the intent to kill, which is an essential element for a murder charge.

Exantus himself told police that, while driving along, he saw a street sign for a “Gray” street, which made him think of “Grey’s Anatomy,” which triggered thoughts of knives and murder for this former dialysis nurse. That, in turn, made him want to “re-enact surgery.”

However, I cannot tell if Exantus also claimed that, at the moment he repeatedly stabbed a screaming six-year-old boy, he thought he was “Dr. Exantus” in the OR. If that were the case, and the jury believed what Exantus had said, it probably would meet the M’Naghton metric.

That is how it was entirely possible for the jury to accept an “insanity” defense in the Exantus case. I’m unclear on how they managed to arrive at the assault conviction, but, as Will Rogers would say, “All I know is what I read in the papers.”

There’s one more twist, though. In the old days, if you were adjudged insane, you were locked up in an insane asylum, sometimes for life, because you were considered too dangerous for society. In other words, the insanity defense might spare you the gallows, but it wouldn’t buy you your liberty. However, we don’t do that anymore either...