The New York Time’s 1619 Project, a series of essays launched on August 18, 2019, sought to “reframe the country’s history” by placing slavery and the later prejudice that was indeed experienced by black Americans “at the very center of our national narrative.” Not electing our own leaders, not the Bill of Rights, not separation of powers. Racism, according to the 1619 Project authors and proponents, defines America’s origins.

In less than a year, the 1619 Project materials were transformed into a curriculum that was taught in 4,500 schools across the country. Since then, there have been national arguments over Critical Race Theory and DEI in schools. One group of professors conducted a survey in which they asked high school students how often they had heard certain phrases from their teachers. The study found that 36% of respondents said they heard the argument that “America is a fundamentally racist nation” often or almost daily.

This “America is fundamentally racist” view, in and of itself, is prejudiced. It labels our entire country because of the actions of a subgroup of people. So, should we wrap ourselves in the flag and avoid acknowledging the darker side of our history? Of course not. But the healthy response is not eternal and unending guilt; self-hate will not bring us any closer together as Americans.

The healthy response is to remind ourselves that we are human; some Americans humans held slaves and some freed slaves. Healing the nation is not about seeing only one side or the other, it is about seeing ourselves in our basic humanity. Author Jacob Needleman put it well in his book, The American Soul: Rediscovering the Wisdom of the Founders:

Like unregenerate man himself, America is both good and evil at the same time…When the real feeling, the deep sensing and pondering of each side of this contradiction begins to appear in us, something entirely new may be glimpsed in our hearts and in our actions. But, for that to happen, we first need to stand in front of each side of the contradiction without impatience and without helpless reactions of guilt or pride. We need to apprehend what is good in America, but without self-inflation, and what is evil in America, but without self-flagellation.

There is currently tremendous focus on the sins of slavery, so let’s ponder the other side, as Needleman suggests. Here are three early voices for the abolition of slavery, a very small sample of good people in colonial America.

Samuel Sewall, Born 1652

Samuel Sewell was a prominent merchant in Massachusetts and Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Superior Court. In 1700, he wrote an essay called “The Selling of Joseph,” using the Biblical story of Joseph’s brothers selling him into slavery as an argument against the slavery of his time. He asserts that from the beginning, after the fall of Adam and Eve, God gave the same rights to all of humankind. He states:

the outward estate of all and every of the Children remains the same, as to one another. So that originally, and Naturally, there is no such thing as Slavery.

God didn’t create slavery, men did. Sowell also criticized the forced separation of Africans from their own land, saying:

It is likewise most lamentable to think… That which GOD ha’s joined together men do boldly rend asunder; Men from their Country, Husbands from their Wives, Parents from their Children.

He responds to the argument by slavery advocates that it is good that slaves were brought here and introduced to Christianity. Sewell’s answer is simple:

Evil must not be done, that good may come of it.

Sewell was one of several early abolitionists who used the Bible to fight against the arguments of slavery proponents.

Benjamin Lay, born 1682

Benjamin Lay was fiery, with absolute confidence in himself and his convictions. He was a Quaker and  helped push the Quakers towards abolition. He was known in his time as the Quaker Comet.

helped push the Quakers towards abolition. He was known in his time as the Quaker Comet.

Lay was a little person, standing just over 4’ tall. He had a booming voice and according to a fellow Quaker, his face held strong features and his countenance was both grave and kind. He wrote forcefully against slavery, but his primary method of teaching was theatrics.

In 1738, Lay entered a Quaker meetinghouse wearing a large coat that covered a sword and a hollowed-out book that held an animal bladder filled with red juice. During the service, Lay rose, threw off his coat and shouted to the crowd:

Thus shall God shed the blood of those persons who enslave their fellow creatures!

He pulled out the sword, lifted the book over his head and plunged the sword through it. The red liquid gushed out and he spattered it on the slave owners. He was ushered out of the room.

One winter, he stood in front of a meetinghouse in deep snow with one foot uncovered. The Quakers who saw him encouraged him to get out of the snow to avoid getting sick. He responded:

Ah, you pretend compassion for me but you do not feel for the poor slaves in your fields, who go all winter half clad.

Lay wrote a book, All Slave Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates. The book was printed by his friend, Benjamin Franklin.

Lay was disowned by the Quakers and became a semi-recluse. He boycotted all products made by slave labor, made his own clothes and ate only fruits and vegetables which he grew himself.

In 1758, a visitor told Lay that the Quakers had begun reforms, including disowning Quakers who traded slaves. Lay gave thanks to God, and said, “I can now die in peace.” His health declined soon after that and he died in 1759.

Anthony Benezet, Born 1713

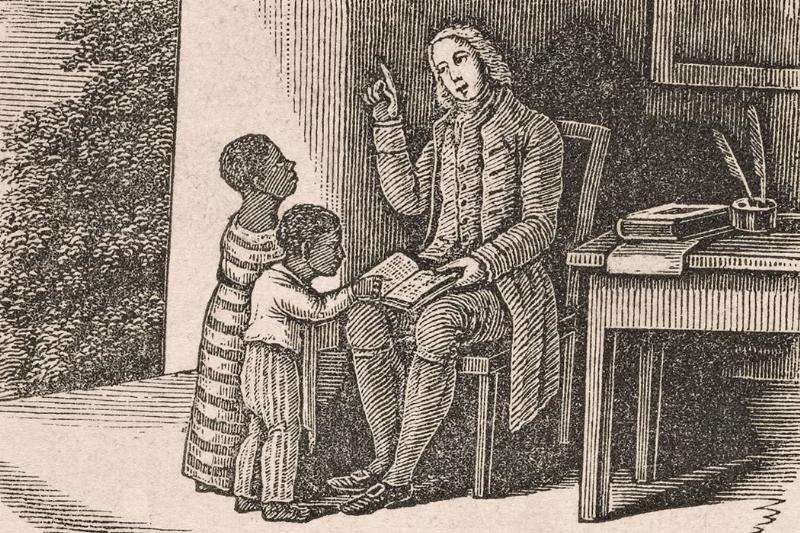

Anthony Benezet was both an abolitionist and a supporter of rights and education for blacks. He was a teacher in Pennsylvania and in 1750 began evening classes for black people in his home. He also started the first secondary school for girls in Philadelphia in 1754.

Benezet wrote several anti-slavery pamphlets, including Observations on the Inslaving, Importing and Purchasing of Negroes (1760), A Caution and Warning to Great Britain, and her Colonies, in a Short Representation of the Calamitous State of the Enslaved Negroes in the British Dominions (1766), and one of the first reports of Africa itself, Some Historical Account of Guinea, Its Situation, Produce, and the General Disposition of Its Inhabitants, With an Inquiry into the Rise and Progress of the Slave Trade, Its Nature and Lamentable Effects (1788).

He co-founded the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. He lobbied the Pennsylvania legislature for abolition, petitioning them to ask King George III to end the slave trade. He died in 1784. In his will he provided for the education of black children.

These three and many other early abolitionists are part of our American history. Knowing about them is how we move forward, how we find each other again. We’re all human. As Americans together, we can believe in ourselves.

Image: New York Public Library