As we approach our country’s 250th birthday, we should remember that our path to independence was long and hard. It required sacrifice, dedication, and someone who could give the quest for independence a voice.

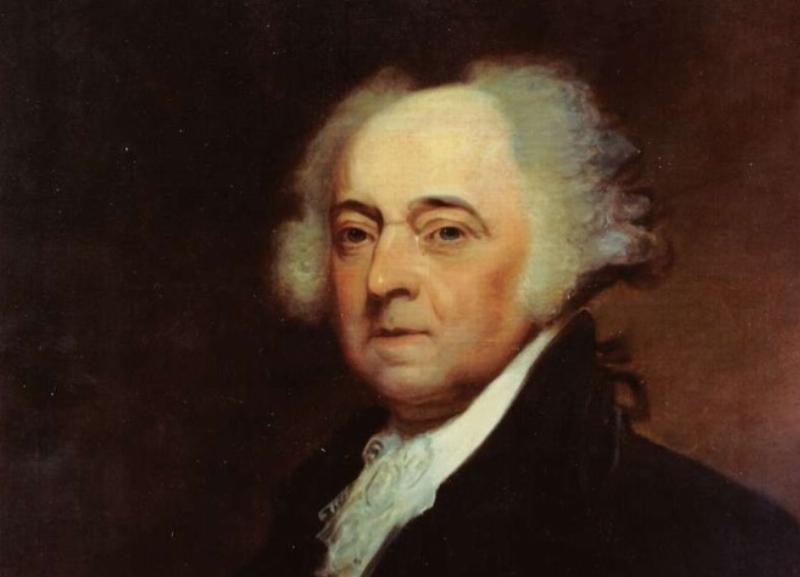

John Adams was that person. Through skillful argumentation and an unwavering focus on liberty, Adams played a pivotal role in determining how and when our nation declared its independence.

On December 16, 1773, the colonists engaged in the Boston Tea Party to protest the British Parliament’s tax on tea. In response, the Parliament passed the Coercive or Intolerable Acts in 1774. That fall, delegates from the colonies convened the First Continental Congress to determine their response to British taxation. John Adams, a representative from Massachusetts, believed that we would have to declare our independence from Britain. He was in the minority.

Most of the delegates believed that the relationship with Britain could be fixed. The moderate faction, led by John Dickinson, a delegate from Pennsylvania, proposed petitioning King George III. The delegates voted in favor of the petition along with a boycott of British goods and a plan to meet again in a year if nothing changed. But the king rejected the petition and further clamped down on the colonies.

The following spring, the Battles of Lexington and Concord occurred. Soon after, the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia.

There, the delegates were divided into two camps: moderates, led by Dickinson, who wished to continue being British subjects but with greater autonomy, and radicals, led by John Adams, who wanted a complete separation from the British. Although the moderates dominated at the time, Adams maintained that the colonists had to defend themselves against British tyranny.

On June 10, 1775, in a letter to Moses Gill, chairman of the Committee of Supplies, Adams wrote, “Powder and artillery are the most efficacious, sure and infallible conciliatory measures we can adopt.” Adams nominated George Washington for commander-in-chief on June 15, arguing in front of Congress that Washington’s military experience and character had prepared him for the job. Congress formed the Continental Army with Washington as commander.

Once again, the Continental Congress voted to make amends through the Olive Branch Petition, but the king once again rejected any reconciliation and, in August 1775, declared the colonies in open rebellion. This response by the British helped Adams convince the rest of the delegates that the colonies should stand united and form a new nation.

The following year, after months of debate, the Continental Congress passed a motion to declare our independence, and Adams immediately seconded it. He was then appointed to a committee to draft the Declaration of Independence. It was Adams who suggested that Thomas Jefferson write the declaration.

In a conversation with Thomas Pickering, who went on to serve as secretary of state under Presidents Washington and Adams, Adams recounted his conversation with Jefferson this way: “Reason first: You are a Virginian and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason second: I am obnoxious, suspected and unpopular. You are very much otherwise. Reason third: You can write ten times better than I can.” Adams was right. The declaration was presented in Congress on June 28, 1776, and Adams defended it on the floor for days.

Later, Jefferson recalled that Adams conveyed his speech “with a power and expression that moved us from our seats.” Robert Stockton, a delegate from New York, wrote that Adams was “the man to whom the country is most indebted for the great measure of independency ... [and] by the force of his reasoning demonstrated not only the justice, but the expediency of the measure.”

Washington was the sword of the revolution, Jefferson the pen, and Adams the voice. The Declaration of Independence was unanimously approved on July 2, 1776.

This Independence Day, let us remember the man who believed in our country from the very beginning. Amid pressure from British incursions and even from his fellow delegates, John Adams brought the United States of America to fruition through grit and love for his home. He was the first to recognize the abilities of Washington and Jefferson, and it was his eloquent argument for independence that led to a unanimous vote.

In addition to leading the Continental Congress to declare independence, Adams went on to become our first vice president, our second president, the first president to live in the White House, and the first president to peacefully hand over the executive office to the winner of the election from a different party. We owe him a great debt.

It is time to recognize Adams’s contribution to our nation with a memorial in Washington, D.C.

Image via Picryl.