Each year, as the Fourth of July rolls around, Americans across the land dust off their barbecues, unfurl their oversized flags, and celebrate their hard-won independence with fireworks, grilled meats, and an impressive disregard for fire safety. It’s a day of pride, patriotism, and, dare I say, more than a little historical creative license.

As an Englishman observing from across the pond, I can’t help but smile at the enthusiasm while wincing slightly at the folklore. Because much of what Americans believe about the War of Independence and its aftermath bears only a passing resemblance to historical fact. It’s a bit like claiming Braveheart is a documentary.

Now, before anyone starts warming up the muskets, let me be clear: I admire America. Your nation has achieved remarkable things, from inventing the Blues to putting men on the Moon and back to inventing buffalo wings. But as you celebrate your split from Britain, it’s only fair someone from the old country offers a gentle but factual reality check.

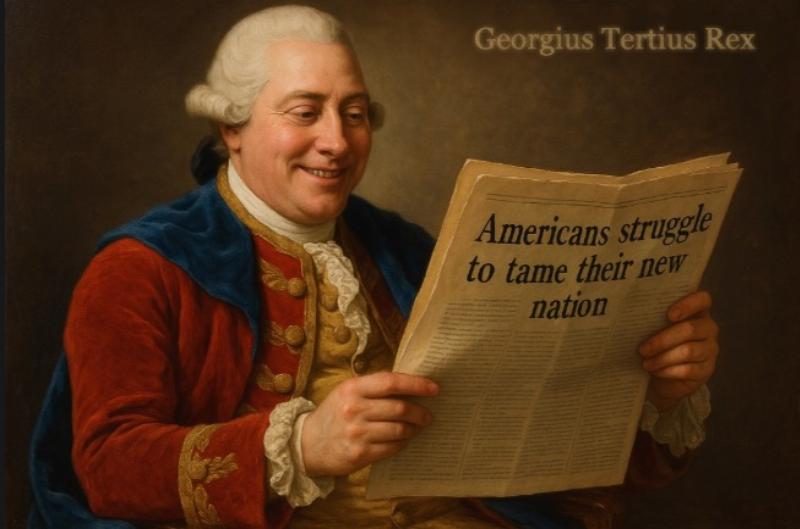

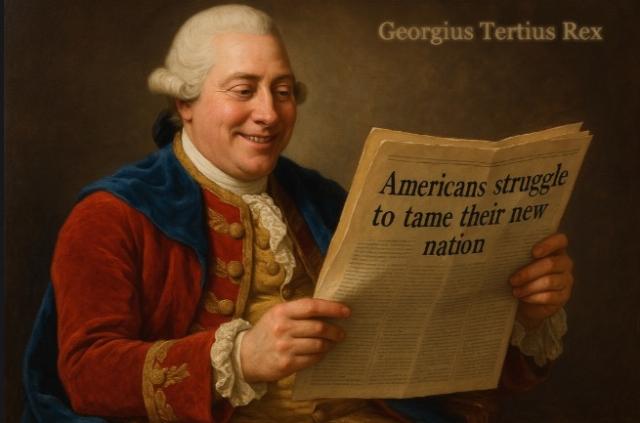

Image created using AI.

One of the more enduring myths is that the American colonists were of one heart and mind in their quest to cast off British rule. In truth? Not even close. Most colonists in the 1770s still considered themselves loyal Englishmen. Their ancestors had braved the Atlantic for opportunity, not revolution. Estimates suggest that only about a third of the colonial population actively supported independence. Another third remained loyal to King George III, and the rest? Ambivalent, preoccupied with crops, debts, family, and, naturally, avoiding infectious disease. Like now, many couldn’t have found London on a map, much less cared to overthrow its authority. The idea that a group of yeoman farmers suddenly declared themselves a new nation is romantic but wildly oversimplified. Most colonists wanted fair treatment within the British system, not to burn it to the ground.

The standard American narrative paints the Revolution as a grassroots rebellion of the common man. But peel back the bunting, and you’ll find it was, in large part, a well-organized coup by the colonial elite. The Founding Fathers were not humble frontiersmen; they were lawyers, merchants, plantation owners, and intellectuals—the colonial upper crust. Their grievances were driven by economics and influence, not simply the tyranny of taxes on tea.

Take George Washington: wealthy landowner, slaveholder, and savvy political operator. Or Benjamin Franklin, who spent years enjoying the comforts of London society before his ambitions met a ceiling. Their frustrations with British policies were real, but so were their personal stakes in reshaping the colonial power structure. The Revolution wasn’t, therefore, a spontaneous outpouring of democratic fervour. It was a calculated effort by prominent men to protect their wealth, expand westward, and cut themselves a larger slice of the economic pie, ideals that, in fairness, have fuelled political movements on both sides of the Atlantic for centuries.

And here’s the awkward bit: for many ordinary Americans, life after independence didn’t look much freer, just poorer and more chaotic. The war devastated the economy. British trade evaporated, currency collapsed, and debt skyrocketed. The French, ever eager to irritate Britain, had lent critical support, but naturally expected payment – with interest. Meanwhile, political unity among the states was tenuous at best.

The much-heralded liberties were also, shall we say, inconsistently applied. Women, Indians, sorry Native Americans, and enslaved Africans, the majority in some colonies, found that their new “freedom” looked remarkably like their old subjugation. Even many working-class white men discovered that promises of liberty did not always translate into tangible improvements in their daily lives.

The first attempt at governance, the Articles of Confederation, was a political quagmire that made herding cats look simple. It wasn’t until the Constitution, heavily influenced by British legal traditions, that the fledgling United States found stable footing. In short, independence brought opportunity, but also disorder, hardship, and uncertainty, particularly for those outside the privileged political class.

American schoolbooks often depict the British as cartoonish villains; redcoats stomping about, oppressing liberty-loving colonists. The reality was more bureaucratic than brutal. The infamous taxes, the Stamp Act, the Tea Act, were modest by European standards. And, inconveniently for the popular narrative, the Tea Act actually reduced the price of tea. But logic rarely stands a chance against the allure of righteous rebellion.

Moreover, the British Crown was attempting to manage the complex realities of empire. The Proclamation of 1763, limiting westward expansion, wasn’t an act of tyranny, it was a pragmatic effort to prevent frontier warfare with Native tribes. The colonists, particularly the wealthy land speculators, simply didn’t like being told “no.” In many ways, Britain’s real sin was underestimating just how determined—and self-interested—some colonial leaders were in seizing control for themselves.

The Revolutionary War succeeded in establishing an independent United States, no question. But the immediate aftermath? Economic collapse, political fragmentation, and increased hardship for many. Worse, the Revolution sparked domestic conflicts that revealed the fragility of the new republic. The Whiskey Rebellion of the 1790s, sparked by, ironically, a federal tax, saw President Washington himself deploying troops against American citizens. The same man who led a revolt against taxation without representation now enforced taxation with military might. History, it seems, has a wicked sense of humour.

Meanwhile, the British quietly carried on. Far from collapsing, the British Empire expanded. By the early 19th century, Britain ruled vast new territories, its global influence arguably greater than ever. And while Americans were sorting out their Constitution (and then fighting a civil war over it), Britain abolished the slave trade, pioneered the Industrial Revolution, and invented cricket, a sport made so complicated that Americans wouldn’t be able to steal it. Instead, they turned into baseball, a game for the simple man.

To be clear, none of this is to diminish American achievements. The United States has, over time, become a global leader in innovation, often after stealing British inventions, industry, and perhaps most of all, popular entertainment. But history deserves honesty.

The Revolution wasn’t a flawless, unanimous struggle for universal liberty. It was a messy, complex, and often self-interested movement led by ambitious men. Most colonists didn’t crave independence. Many suffered more, not less, after it was achieved. And the promise of freedom? That took generations and continued struggle to materialise for all.

So, as you recover from the food, the fireworks, and the patriotic songs, consider raising a glass to your British cousins, the imperfect, tea-drinking colonists who sparked your nation’s birth.

After all, without us, you’d have nothing to rebel against.

God Save the King—and pass the ribs.